This article aims to revisit my PhD research work, which examines the war image as a tool for the construction of History. Stemming from my personal history as well as various types of visual representations of war, this body of work began in 2009 when I came across visual archives of the Gulf War belonging to my father, a military veteran. Through these photographs, news clippings, videos, and other documents, I became interested in how war can today be seen as a vast field of perception, one that is transforming our visual environment. These images became my basis for studying the different regimes of visibility within contemporary representations of military conflict, in order to determine how much of itself war actually reveals through the images it produces and broadcasts, and to question both the artist’s position and process when handling and working with such documents.

The issue of warfare images is more topical than ever. Considering the simple fact that we have an obvious need to document the world through images, we can assert that warfare images rely on a variety of visibility trajectories that force us to invent new ways of seeing and thinking about History. As new means of production and broadcasting permeate our daily lives, it has become increasingly necessary that we offer an alternative perspective on these types of documents. This alternate perspective, which I describe as off-centered and un-subjectified, questions what the author’s intention and position are in the process of producing and broadcasting such documents. How does this affect the conveyed meaning? Where does the truth lie? By documenting the world, we create images and archives that redirect the meaning and origin of these documents. The discrepancy between an image which was, on one hand, made with no particular intention, and on the other, used as an archival document, creates a gap with its author, who completely disappears as soon as the image ceases to be considered for the reason it was initially made. Surely, the aforementioned concept of un-subjectification raises crucial moral issues as well as the issue of responsibility—the responsibility of members of the military, politicians, and journalists, but also the responsibility of artists who choose to work with this documentary material.

Documenting the world

Since the beginning of the history of conflicts and their representations, war and imagery or war and representation have been intertwined, with no such thing as one existing without the other, and History seems to have been shaped by the different conflicts that have traversed it. In fact, according to Pliny and the myth of Butades, it was a young man’s departure for war which led to the first-ever work of representation. Most studies on the myth place the main focus on its relevance in terms of the origins of painting, drawing, sculpture and photography, but rarely do we find any mention of the relation between the act of creation and war. And yet, it is only after his daughter’s lover leaves for war that the potter Butades creates his sculpture.

Above all, documenting the world means bearing witness to events in order to inform and educate, and is ultimately an act of memory. Visual archives, be it the work of the historian or of the artist, call upon and invent new ways of seeing and thinking about History. In order to make History, however, the document-of-proof questions the visual testimony in order to recount the facts, and assumes the position of an image that, in principle, cannot be called into question. Nevertheless, the arrival of new broadcasting technologies has begun to rattle the image’s presumed authenticity. As a result, we must rethink our ways of seeing by deconstructing the usual trajectories of our gaze.

Bringing our gaze to the edge of the image means moving it out of the traditional framework of representation, because visual works are a vessel for fostering memory, be it personal or collective, within another timeframe. In this sense, this new vantage point on the archival document recalibrates our gaze, allowing it to approach visual images differently. The reason we archive is to preserve, to keep a trace, a memory, a testimony of what was. The archive necessarily raises the question of the document’s source—where it comes from, who produced it, and how it managed to reach present times. But what about the document’s authority? The image appears to surrender its authority to the person making use of it. But what becomes of this authority when the archival document is no longer put to the use for which it was initially intended, for which it was produced? For “We can make an archive mean anything and everything we want.”1

Transposing an archival document into a different field and, in particular, re-employing it in the field of art, can offer a way to understand and question the document’s origins, as well as the knowledge enclosed within it. Through art, a new narrative emerges, thereby raising the question of the archive’s status. The artist becomes a spectator, a viewer/reader of a storyline which offers these documents a new kind of visibility. By re-establishing the archive—specifically the visual archive—within a new form of representation, it is the power and the authority of the document that are called into question. An artist’s practice can easily position itself in the dissolution of the document as a new way of existing in the world, of inhabiting it. The archive is a focal point, surrounded by an entire network of knowledge and information that participates in recomposing History and its events. It is the point where the confrontation between meaning and accuracy takes place, where History is not a succession of facts but rather the theatre for the disparity between the truth and the task of identifying events—which in fact may be where the artist’s work comes into play.

Art and the reality of the archive

Both the artist and the historian share the task of establishing a link between the present and the past which is to be re-opened, but they differ in their attitude toward the document’s source. The historian’s approach will be to build a narrative of the archive based on the historical events to which it testifies. The artist, too, will work on the access the document gives us to the past, but will, in addition to that, introduce from time to time a fictional or even fictionalized dimension to their work. As such, what the artist offers and brings into the flow of information, deals with the coexistence of truth and fiction, the latter being a useful tool for questioning the former. In this case, what is constantly called into question is the material’s authenticity, the access it grants us to the past, and the accuracy of the established narrative surrounding the document.

In this way, the archive’s role could be described as a “dialogue with History,” a bridge connecting past, present, and future that continually reinvents and redefines the frameworks of memory as well as the relationship between the private sphere, the collective sphere, and History. Memory, when considered and defined through the use of archives, is perhaps the invisible place in which a presence is formed, a place leading to the permanent search for a territory in which areas of oblivion manifest—places of absence, spaces which are void and empty, inviting us to rethink History differently by offering new kinds of visibility in the face of History’s tragedies. The issue of the representation of warfare and extreme violence has raised a number of questions, starting with the trivialization of the viewer’s gaze in the face of such events. We find ourselves, in fact, positioned in an ongoing back-and-forth between sight and sight deprivation—in other words, blindness and even a refusal to see. Proposing to re-present History also means to risk distorting, reinterpreting, and perhaps even betraying memory. It also means taking on the risk and responsibility of taking a position, all the while questioning the event’s veracity.

To make believe: visuals of warfare in contemporary art

Warfare must therefore be examined in relation to our gaze. Since the Gulf War, a conflict which marked a turning point in the way we think about and represent war, the world has become one giant screen onto which images appear, one after the other, in a constant and increasingly rapid flow and flux. From that point on, images of warfare, as they had been considered, shown, and imagined up until then, would never be the same. The 1990 Gulf conflict showed us nothing. “No one saw anything” are the words most used to describe this conflict, whose representation was non-existent. The control of information transformed the relationship between the representation of warfare and the news media forever. The Gulf War, a late 20th-century conflict, offers a new way of reflecting upon the world, in light of the triangular relationship between image, propaganda, and democracy, to which it served as a magnifying glass. In between propaganda and the supremacy of image over information, the Gulf War embodied a true crisis of representation. Where, then, does the visual image stand in this conflict, tied as it is to the news and to the degree of accuracy of information? “The news you see in times of war are, to a large extent, contradictory, and, to an even larger extent, false.”2 Today, as excessive media coverage and power tactics have brought about absolute control over wartime news and information, Clausewitz’s prophetic claim remains as relevant as ever.

The constant flow of information that was masterfully conducted during the months the conflict lasted managed to fool the vast majority of television viewers, caught in the deceptive yet convincing illusion of watching “History Being Made Live.” In fact, the visual rendition of the Gulf War contributed to the grand restructuring of the world that began with the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, and in that same process justified the West’s intervention in the countries of the South. The supremacy of audiovisual media in the race to power could now exert its boundless influence, slowly allowing for reality to exit the screen which had now taken the place of the real Vera Icona. In 1991, the film critic and journalist Serge Daney inquired: “What does it mean to be responsible for what we transmit?” At the time, the war was constantly televised, it was ever-present. Today, visual representations of war, or at least our attempts to offer an alternative approach to these representations, lead us to consider warfare violence as a key factor contributing to the total dissolution of the gaze—of what it means to see—and this dissolution goes hand in hand with the near-total dehumanization of that which constitutes contemporary war. In the paradoxical words of Paul Virilio: “The first victim in any war is the concept of reality.”3 Rendering the invisible visible and attempting to decipher images indefinitely, would therefore be this space’s artistic and military ambition: the never-ending conquest of the image.

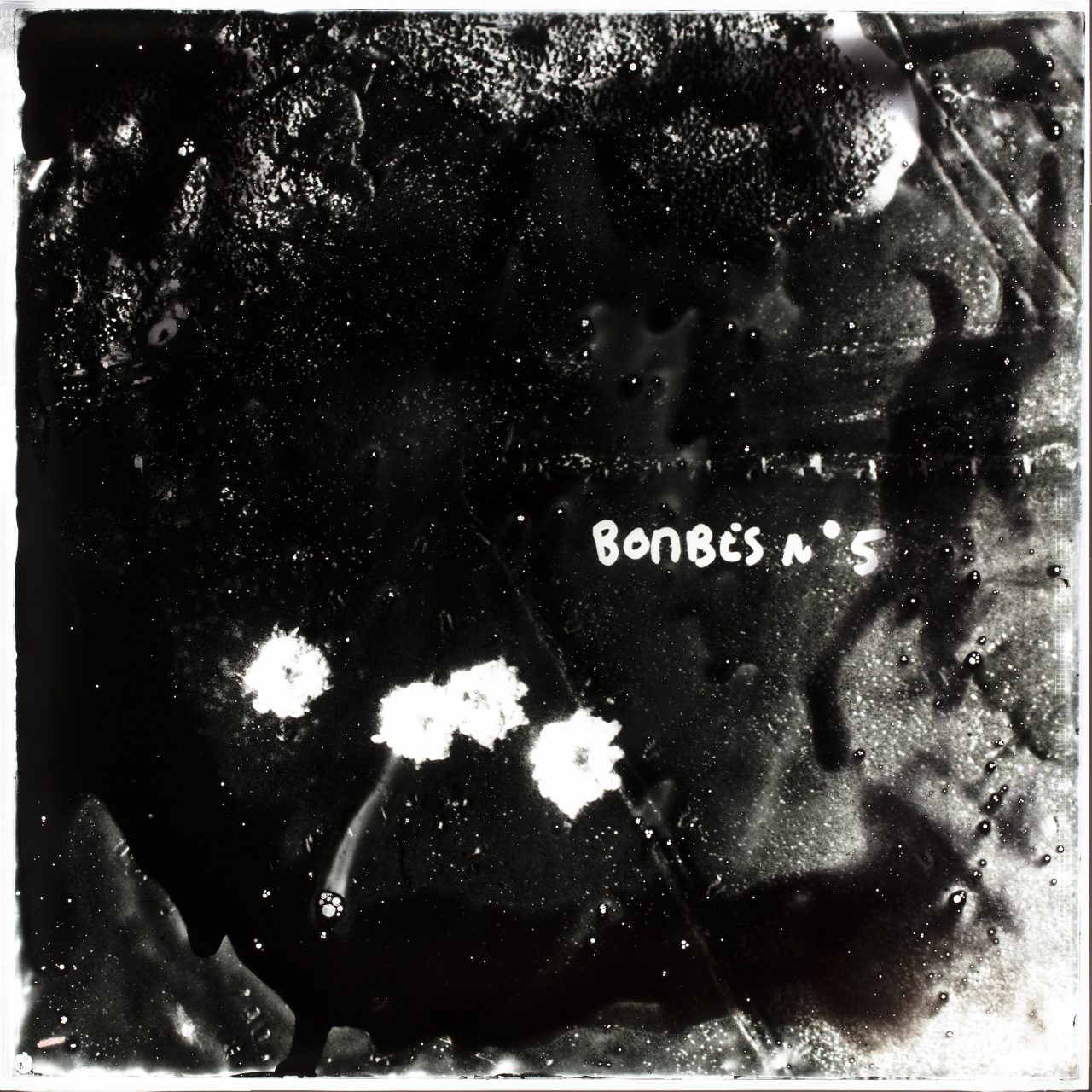

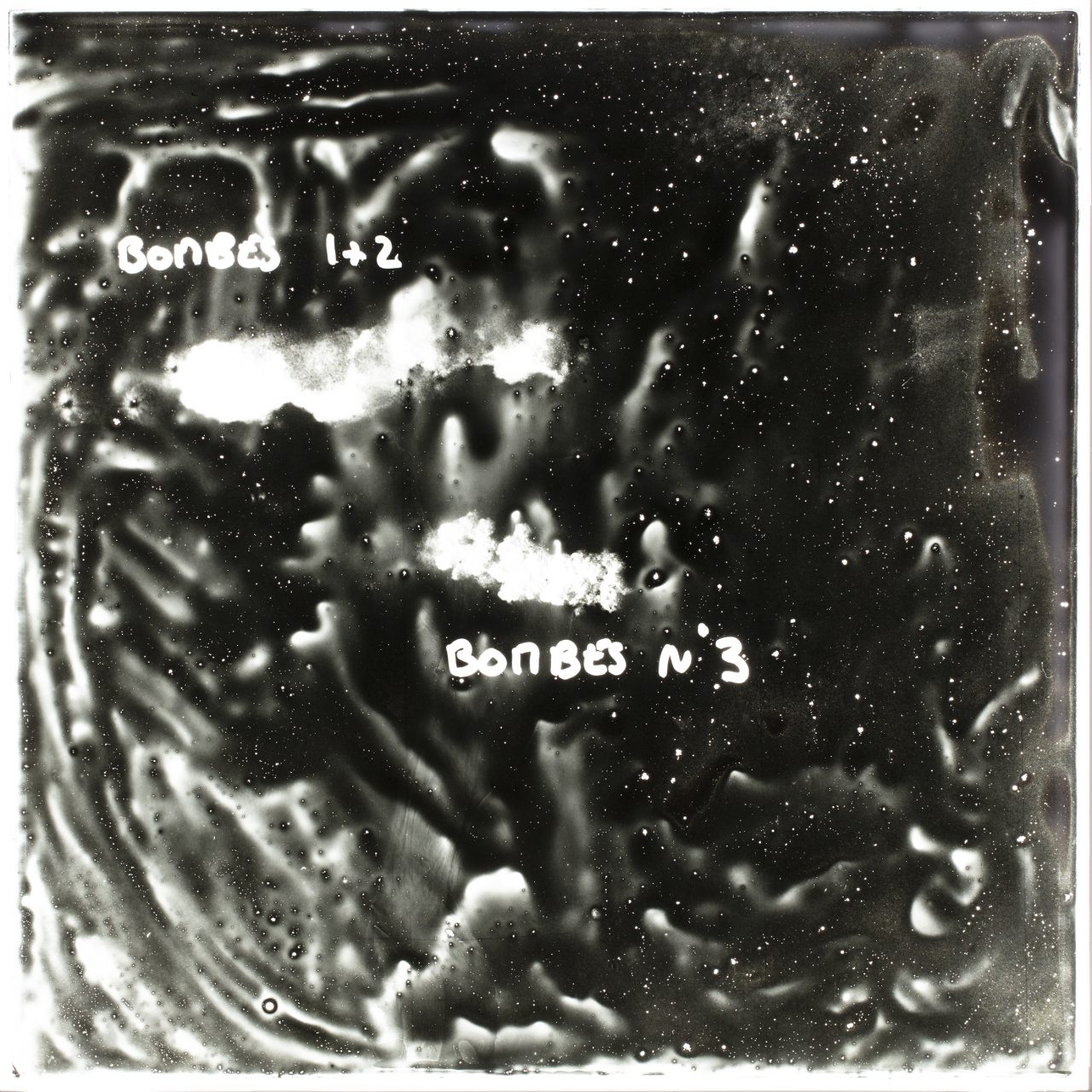

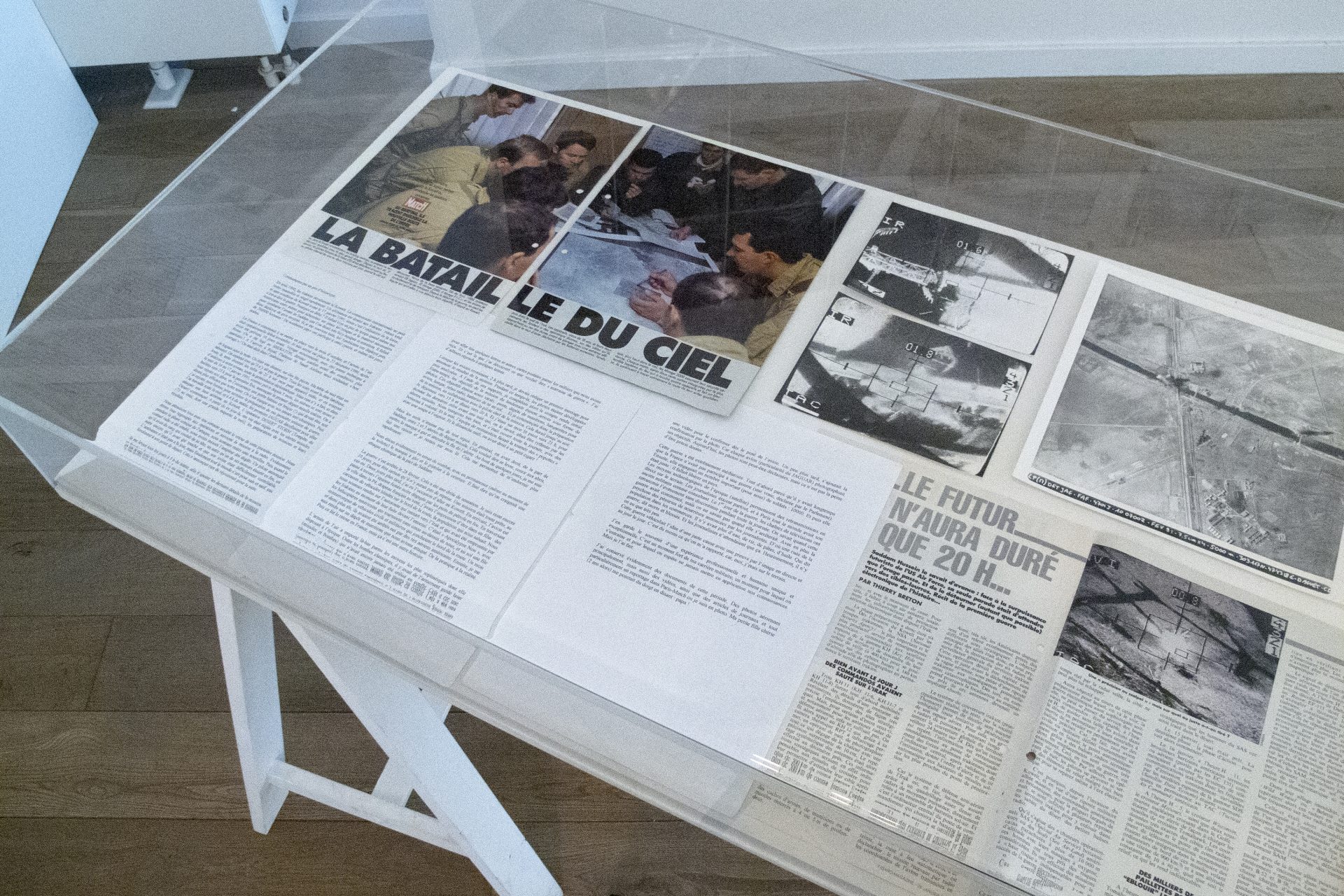

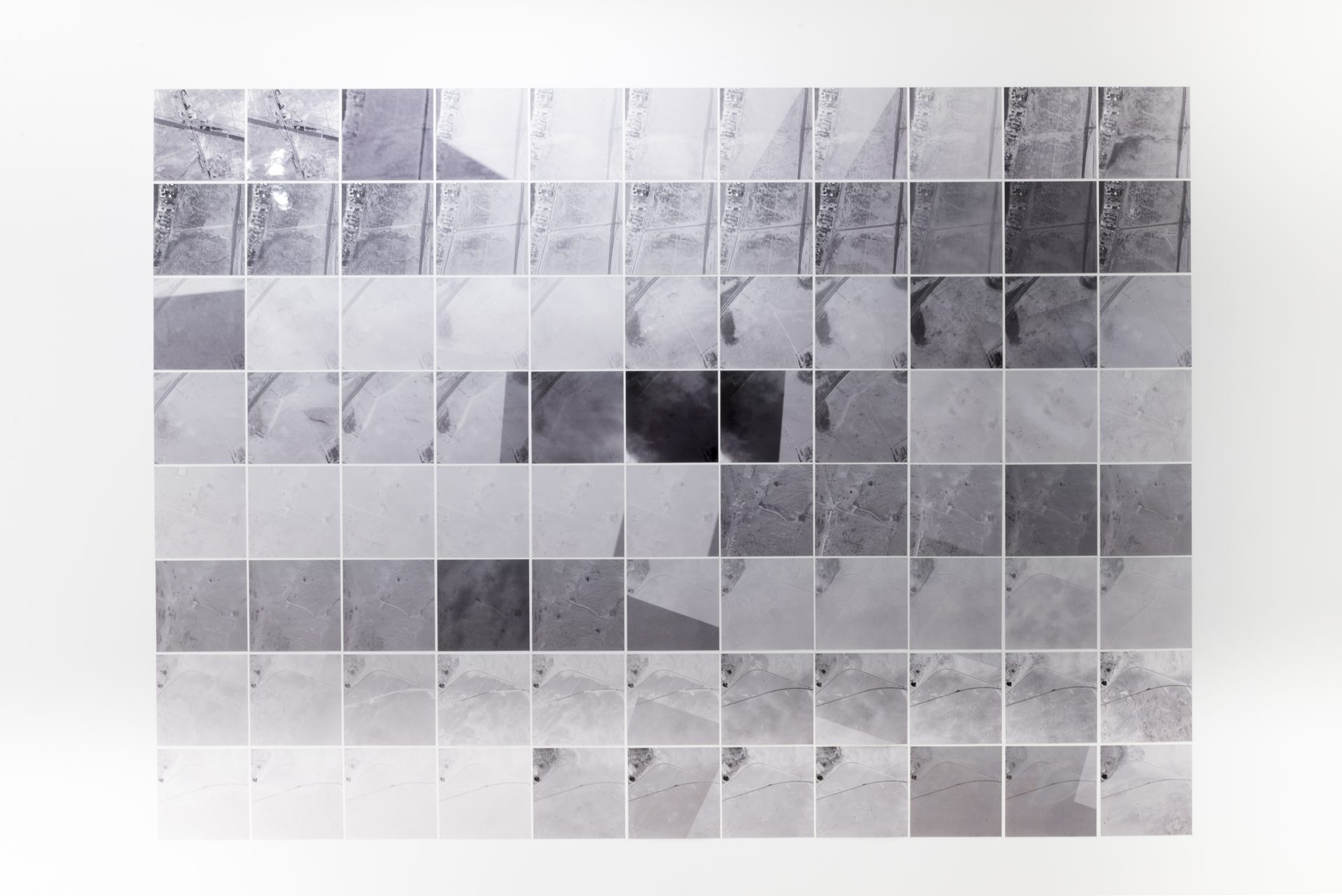

The various projects I have worked on in relation to Gulf War archives were created over the years 2009 and 2019, after gathering information on these documents. Long discussions with my father later brought in decisive elements regarding the understanding of these military photographs. At the intersection of various disciplines such as art, social studies, astronomy, and even geopolitics, the project has unfolded as one long interview compiling several elements—a written statement by my father, an audio clip of comments made by pilots during air raids, images of bombsites taken from Google Earth, and visual archives transferred onto glass plates initially intended for mapping the night sky, thus forming new images which call into question the visual representations of our time and society on a broader level.

The use of these photographic archives in my artistic work starts with dissociating them from their private and emotional origin in order to create a public proposal in which the viewer is asked to question what they are being shown and where it comes from. The act of documenting implies a pre-existing intention to preserve something that has been formed as a testimony—as an archive of the world, so to speak. These images and their status thus find themselves thrown into an alternative orbit of circulation, in which the object is to question their informative value, as much as its disappearance.

By relocating these documents into the field of artistic creation, my intention was to shed a light on the random quality of warfare images, on the confusion they can generate, and on the illusion they give us of better understanding world events. Understanding the image and understanding what we see of and in an image requires educating our gaze. This aspect in particular is what caught my attention with the photographs of the Gulf War. In front of abstract, gray, seemingly sanitized aerial-view images, I found myself incapable of deciphering them and understanding their meaning, namely because the use and proliferation of aerial-view images seems to bard us from ever actually seeing the reality of warfare. I found myself in front of documents which were meant for expert eyes only—they had been produced within a military context, with military technology, for military soldiers. Through this kind of imagery, I became aware that the world, deprived of a horizon line, dissolves, and that vision, deprived of a vanishing point, loses all chances at identifying anything. The military member will focus on analyzing the document. To them, the document is a reference of a specific reality that must be examined as precisely as possible. The media, on the other hand, will transform the document into an image. Finally, the artist, in displacing the document, holds up a mirror to us our own deprivation and the deprivation of the world as it stands before a surface in total confiscation.

Exhibition views Reconnaissance at the galerie Eté78, Bruxelles, 2020

References

1 Arlette Farge, Le goût de l’archive, Seuil, Paris, 1989, p. 118 (see English translation, The Allure of the Archives, by Thomas Scott-Railton)

2 Carl von Clausewitz, De la guerre, Minuit, Paris, 1955, p. 107 (see English translation On War, by Otto Jolles)

3 Paul Virilio builds on Rudyard Kipling’s quote, “The first victim in a war is always truth,” in War and cinema I. Logistics of perception, Les cahiers du cinema, éditions de l’Etoile, Besançon 1984, p. 44

Hélène Mutter is a visual artist, a PhD holder in Art and Art Sciences, and a researcher. In 2020, she will defend her doctoral thesis entitled “La guerre à l’épreuve de l’image – Art et dispositifs visuels”. She is also a member of the executive committee of the CIREC, the Centre de Recherche-Création sur les mondes sociaux, which aims to strengthen the links between creation and research. Her work is situated at the crossroads of artistic work and theoretical reflection that questions the architectural, urbanistic and technological dimensions of war, through the images it produces and conveys.

Hélène Mutter is a visual artist, a PhD holder in Art and Art Sciences, and a researcher. In 2020, she will defend her doctoral thesis entitled “La guerre à l’épreuve de l’image – Art et dispositifs visuels”. She is also a member of the executive committee of the CIREC, the Centre de Recherche-Création sur les mondes sociaux, which aims to strengthen the links between creation and research. Her work is situated at the crossroads of artistic work and theoretical reflection that questions the architectural, urbanistic and technological dimensions of war, through the images it produces and conveys.