Charming hybrid and fantastic animals, drawn on Parisian walls by Codex Urbanus, question us through their mischievous look on the place of street art in contemporary art, on the architecture, history and heritage of our cities.

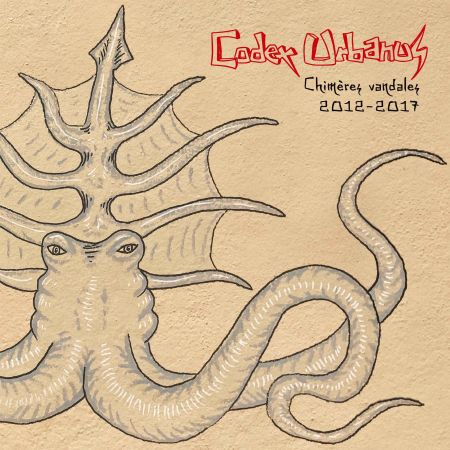

The Parisian pedestrian could be distracted by strange ephemeral chimeras that haunt the walls of Montmartre. This fauna, exposed impermanently, is the work of Codex Urbanus, a street artist for the past ten years. The author of these fantastic animals is also a guide at the Orsay and Louvre museums and has written an essay on urban art: “Why art is in the street” (Pourquoi l’art est dans la rue ?). He regularly exhibits in galleries but also in unexpected places such as the sewers of Paris or the Château de Malmaison. He has also published Chimères vandales, an art book containing an inventory of over 400 fantastic creatures drawn directly on the walls of Paris between 2012 and 2017 (to be published in October 2021 by Omniscience). The book will be the subject of an exhibition of original drawings at the Cabinet d’amateur, 12 Rue de la Forge Royale, 75011 Paris, from 21 to 31 October 2021.

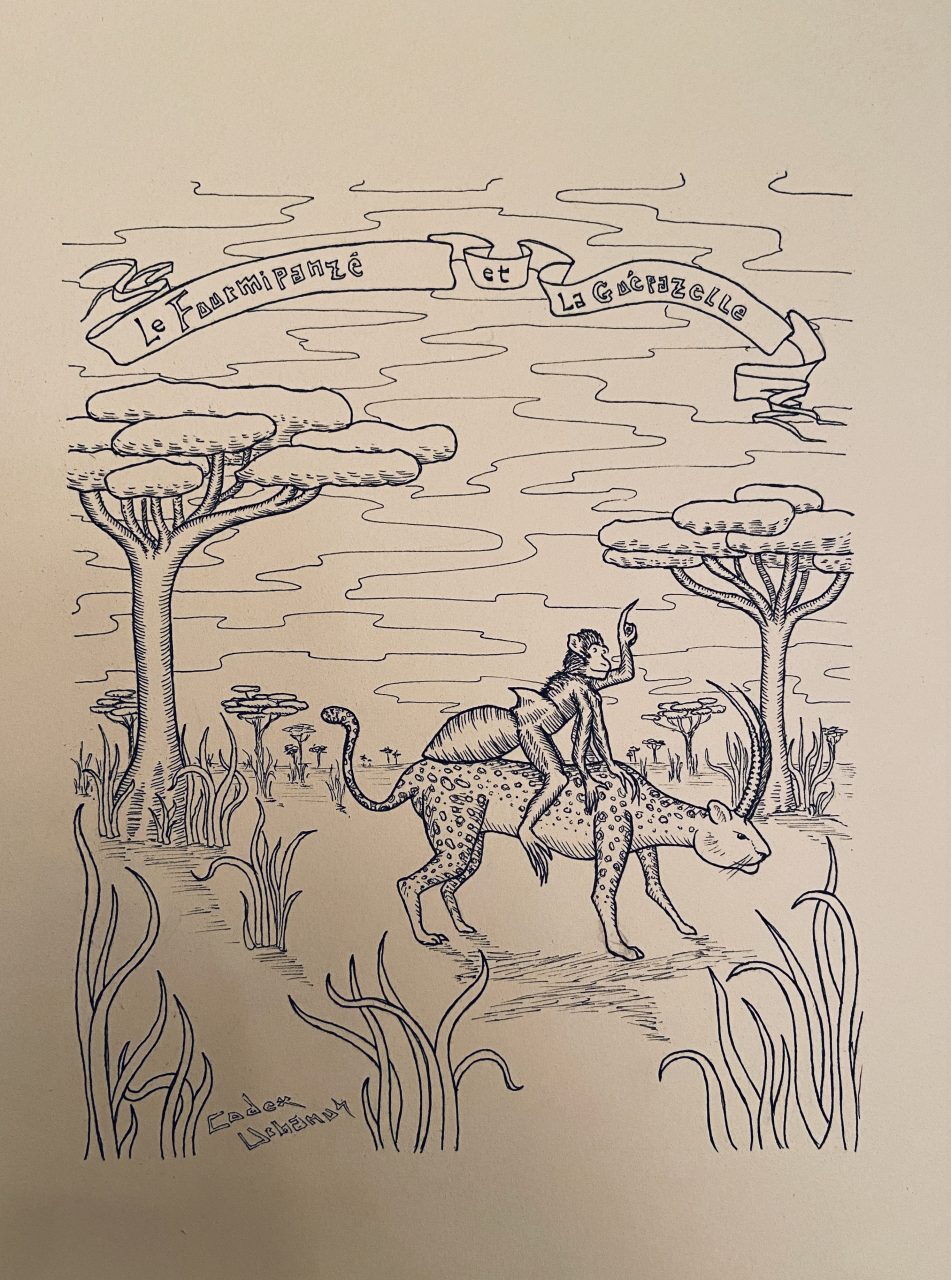

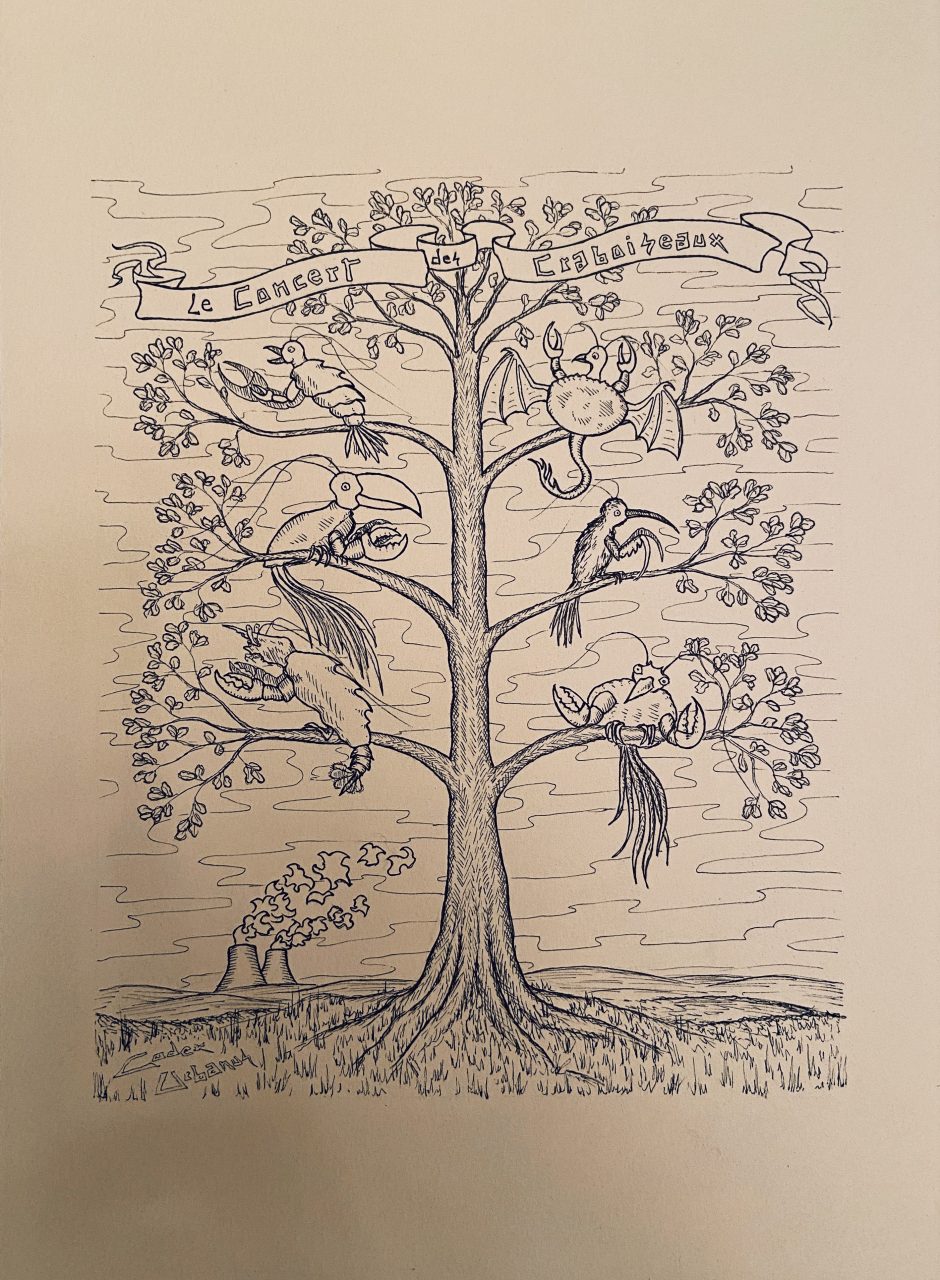

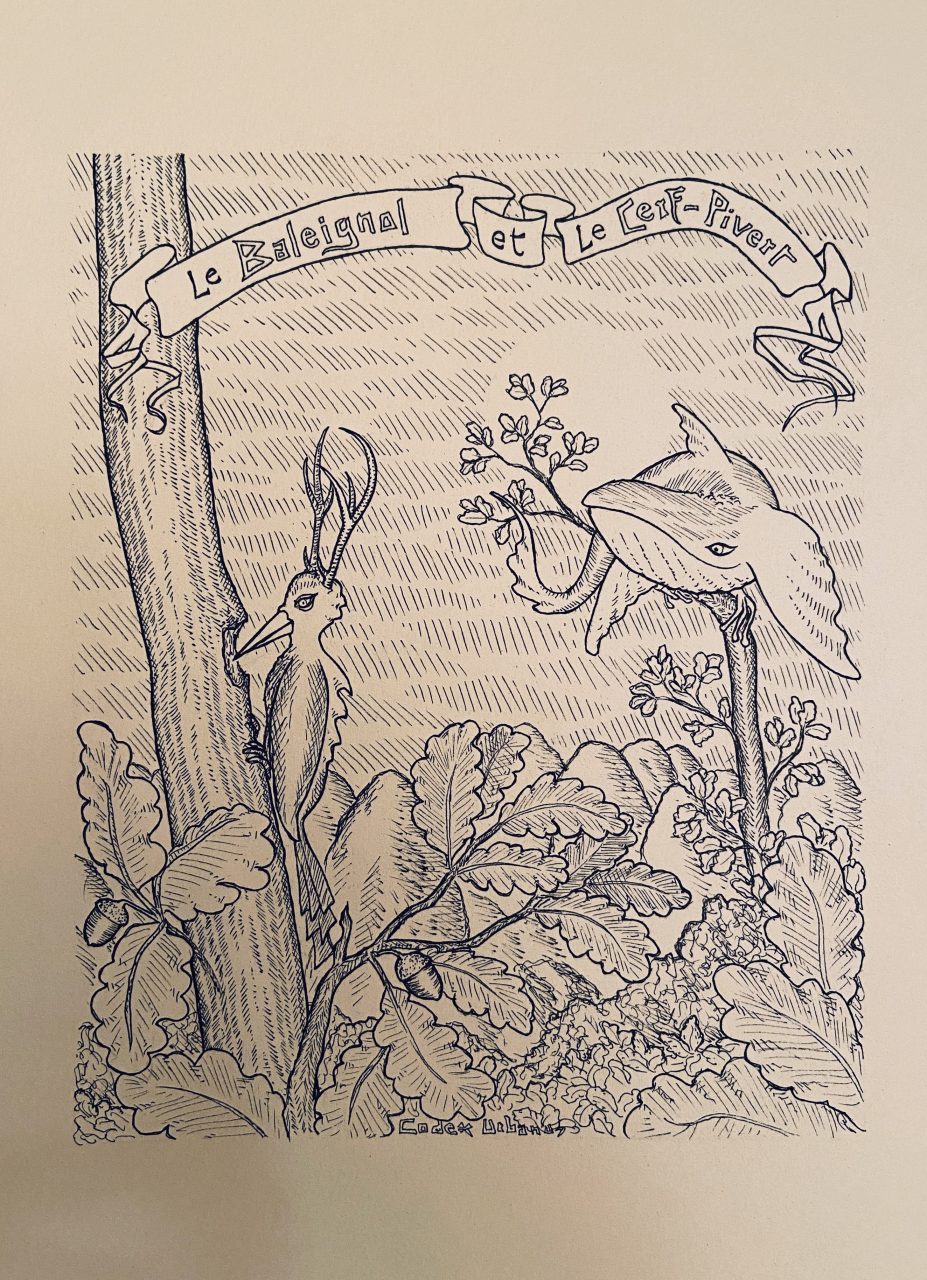

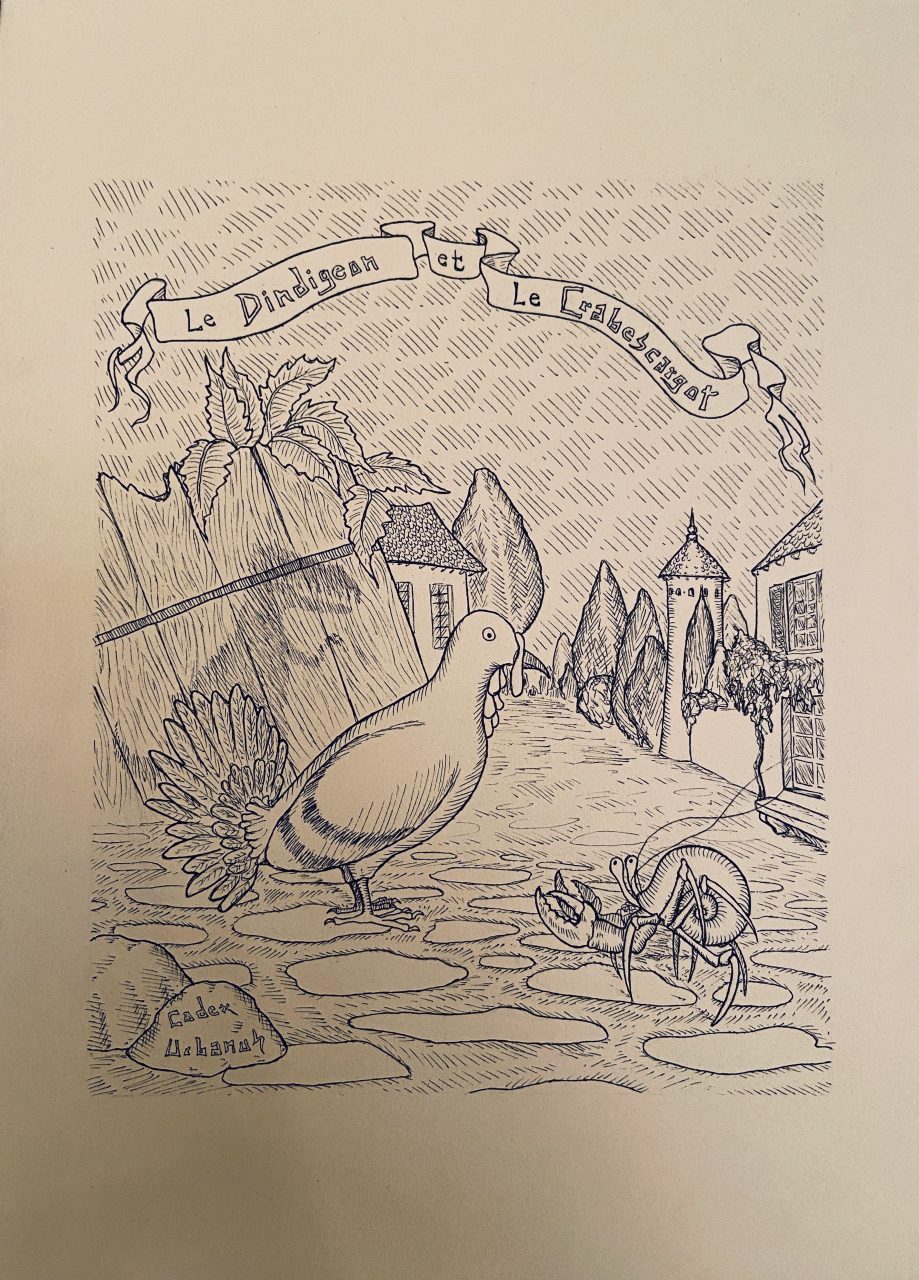

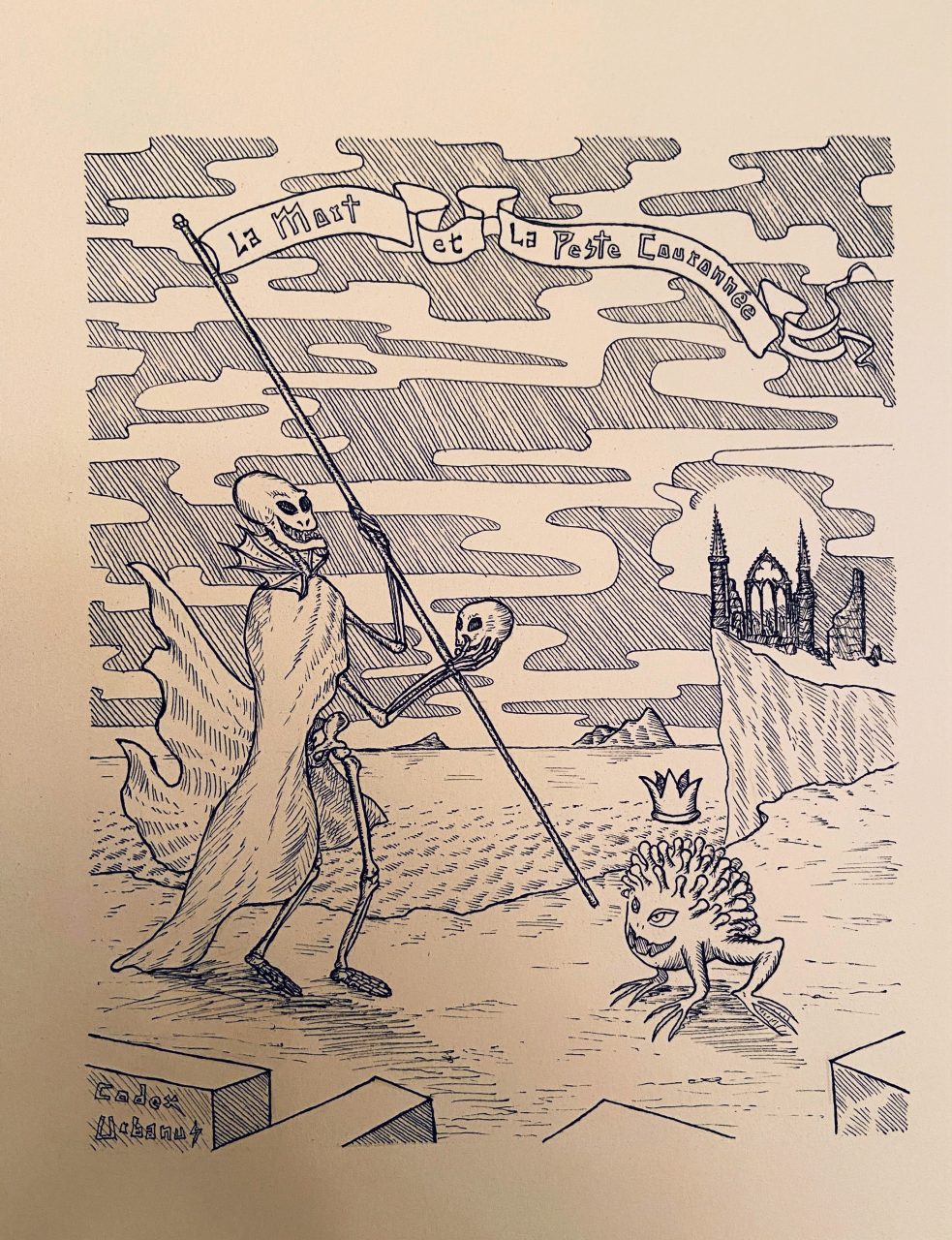

As a tribute to the 400th anniversary of the birth of Jean de la Fontaine, he has started writing – also on the walls of Paris – 50 illustrated fables which will also be published. An urban route is created along the Petite Ceinture between the Porte de Saint-Ouen and the Porte de Clignancourt.

What is your definition of street art?

For me, street art is a movement in which people place art in urban public space for free, systematically and WITHOUT AUTHORIZATION. This is its only specificity, because there is no example of people who did this before the 60s in the world, and this allows to give it its coherence: street art has no unity of form nor content, it is coherent because of its freedom linked to the absence of authorization (and whose corollary is often illegality).

How did you get into street art?

I’ve always drawn on sheets, from school to company meetings. Then in the 2000s, I stopped working in companies to be more nomadic and I felt a lack. But at that time, through my occupation as a guide, I discovered street art, and after a while, I said to myself that maybe I would like it. And we can say that the affinity is mutual…

Can you link your activity as a guide to that of a street artist?

There is a link with the genesis of my own street art activity. I initially became interested because American tourists asked me for a street art tour in 2008. Then, I discovered that it wasn’t just a delinquents’ thing, but an artistic movement. And like it happens for many people, once you get interested in it, that’s all you see: where previously there were only streets for me, I found an open-air vandal museum. My work as a guide has also given me a better understanding of this movement. When you are used to lead visits at the Louvre or Orsay museums, you have a perspective that allows you to have a better understanding of the history of art than the experts of contemporary art who have missed the importance of street art and graffiti.

What is your relationship with the city, its heritage, its history?

I always have two readings of cultural heritage sites, wherever I go: a real, historical, classical reading, and a dreamlike reading, where I use what I see to build things that cannot be seen. As such, I am a huge consumer of culture and travel. Paris is probably the ideal city for people like me, because it is both huge and intense. It’s impossible to say that I’ve seen everything in Paris – 40 years later I’m still discovering things – and there’s an absolutely insane density of things to see, some of which stood up to the assault of time, like the Hôtel de Lauzun, the Grande Synagogue des Victoires or the Réservoir de Montsouris. Humans in Paris are lucky enough to have one of the world’s most beautiful labyrinths in which to lose themselves, and street art settles in its interstices to complete the magnus opus that is Paris.

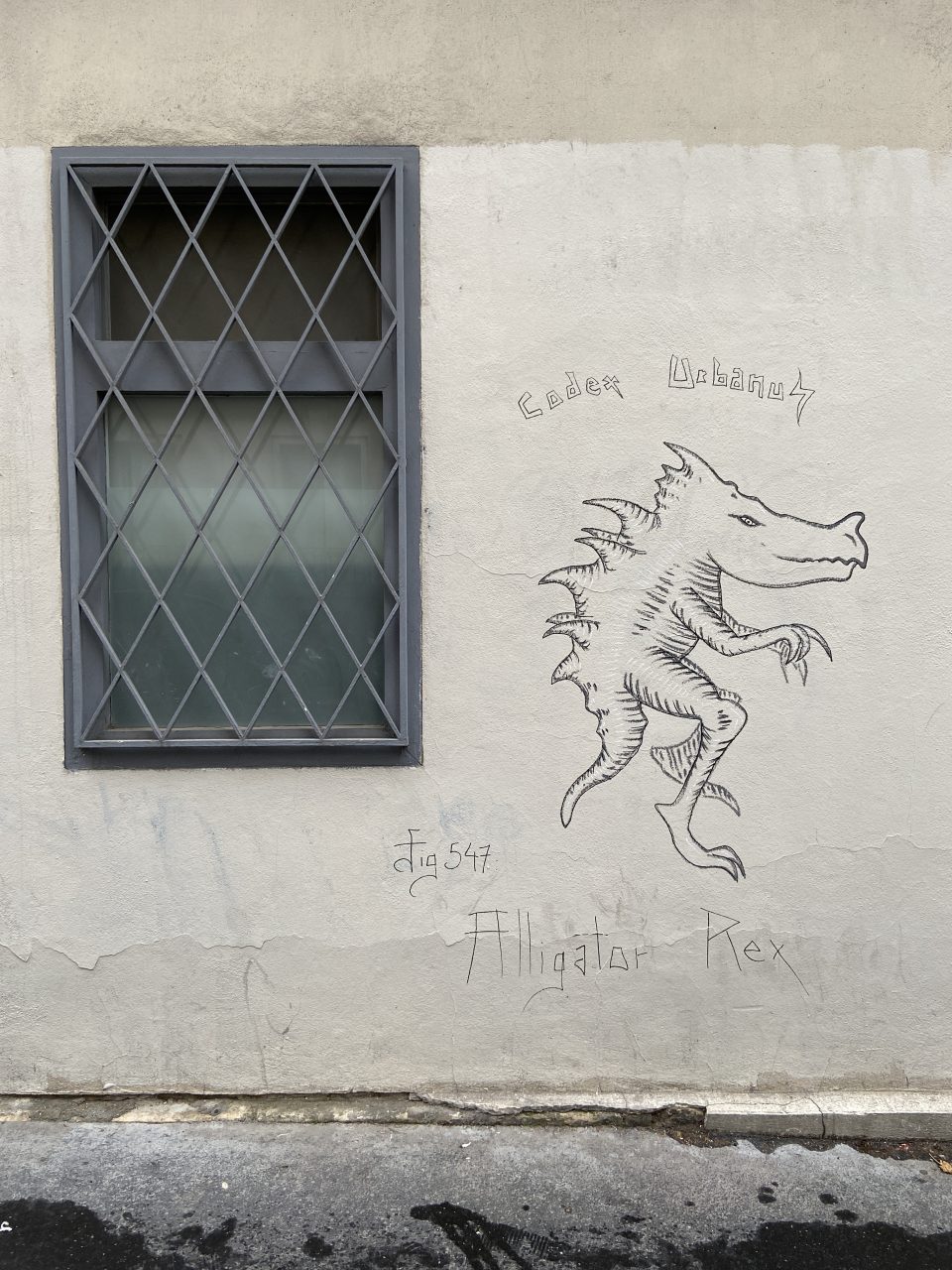

Your numbered chimeras seem to form a kind of bestiary, a treasure hunt, in which the Parisian pedestrian tries to find a meaning, an order… like your artist’s name which seems to suggest an urban collection… Is there one or is it more of a joyful and carefree approach?

A bestiary is by definition a collection – an animal alone cannot constitute a bestiary. And the very idea of “Codex Urbanus”, which means “Urban Manuscript” in Latin, is precisely to create a kind of fantastic bestiary on the concrete pages of Paris. But it’s just a structure, for each chimera, apart from respecting the naming, the numbering and the drawing with 3 paint markers,I take my liberties drawing and only know at the last moment what I’m going to do… It’s a bit like the Haussmannian specifications which gave the size of the buildings, the angle of the roof or the number and locations of the balconies, but which left the architects free to create in their style, which went from neo-classical to art deco while respecting the rules…

Your chimeras sometimes leave the street to go into the sewers of Paris, the Château de Malmaison, the Galleries… Can street art be both inside and outside? Can we still talk about street art?

Street art is necessarily in the public space and without authorization in my eyes. So it is impossible to have street art in the sense that I understand it in a gallery, a museum or even a festival. On the other hand, I am only known through street art, i.e. through my unregulated activity in the street. I’ve had been drawing for 30 years before I started painting on the street but no one cares, it’s Codex that interests them. It’s Codex that people come to see in galleries or museums, so it’s street art that people are looking for. So the label “street art” that is used for these events is both false – it can’t be street art – but it is a street art artist. It’s a bit unanswerable, and it’s not satisfactory because if you remove this street art label, you lose some of the people who don’t see themselves in it, and if you leave it in, you tend to make people believe that street art can be legal and lucrative, which is clearly false. Some people try to invent terms to qualify it, like “inter mural art” or “contemporary urban art”, but I don’t think we’ll be able to get out of the vagueness on this point…

You don’t limit yourself to walls – “the shape of a city changes, alas, faster than the heart of a mortal” (Charles Baudelaire) – since your works also appear on paper: books, engravings, silkscreens, old newspapers revisited by your mischievous coloured chimeras… and on Instagram, photographs of the ephemeral that become permanent. What is your relationship with the impermanence of street art and this evolution towards more permanent media?

I’m not a fan of impermanence personally. The ephemeral aspect of street art is a collateral damage of its lack of authorization, and the artists who say they love it don’t seem to be telling the truth! On the other hand, what interests me is the aspect of degradation. I’m well aware that if I’d had to ask for permission to draw one of my weird monsters I would never get it. Even today there are plenty of official things I’m not invited to because what I do doesn’t fit with the image people have of street art, which is necessarily monumental, colourful and sprayed. So the question of knowing to what extent I am making art or degradation arises each time I create: is the street better or worse after I was there? To reflecting upon this essential question, which is central to street art in general and to my urban work in particular, working on old documents is ideal: is a Napoleonic poster from 1808 better or worse after I’ve drawn on it with Posca?

Then there is the question of reproduction and uniqueness. Personally, I’m fascinated by one-offs, the idea of being in front of a drawing on which Leonardo da Vinci, Gustave Moreau or Salvador Dali worked in real life transcends me much more than multiples. The pieces I make in the street are unique, when they are erased, they are lost forever (unless I become so famous that they are restored under the layers of paint of the town hall!) Photography, since it is digital and therefore easy and infinite, is a kind of insurance: however ephemeral it may be, the practice of street art is digitally eternal because of their presence on clouds. If there is hardly anything to see of my work in the world in real life, there are thousands of photos to discover on the internet… Nevertheless, it’s not the same as meeting a chimera on a wall in Paris…

Is the life of street art dependent on social networks?

Street art is not dependent on social networks – it existed decades before the emergence of these – but there has been a boom following these social networks which have fulfilled their role well, by allowing easy and constant meetings between people who previously rarely crossed paths: street art followers, photographers, collectors and gallery owners. I experienced this very quickly when I started out, as I had no contacts in either street art or contemporary art, and I could see how quickly links were forged on the networks. It allows us to set up projects, to collaborate, to participate in events, I think it’s rather virtuous as long as we cut out the negative aspect of these networks which consists in letting ourselves talk about something other than our artistic activity. Today, we could do without social networks, but this would paid for in lost opportunities and contacts….

You have started a project based on Lafontaine’s fables where you invent new chimeras and write poems in the manner of … Can you tell me about the genesis of the project? How many do you plan to make? A new treasure hunt for the attentive Parisian, which will conclude with an exhibition? a publication? something else?

I try to do different projects every year, and 2021 is the 400th anniversary of the birth of Jean de la Fontaine. So I wanted to create new fables, the Fables Subies (Undergone Fables), since they are imposed on passers-by, as opposed to La Fontaine’s Fables Choisies (Chosen Fables), mine being original, whereas he was inspired by those of his predecessors (Aesop or Phaedra in this case). I therefore set about designing 50 fables, to display one per week, featuring my chimeras, with both a text and a drawing. It’s a lot of work, especially as I have to find not only adequate chimeras – if you know that the hare is fast and the tortoise slow, what about the beetle-giraffe? – and to find a nice story with a morality, all in a few months and while working on the side, it’s very ambitious but I’m very happy with the result. These fables will perhaps be shown in an official urban tour in Paris, and there will be a collection that will come out in the fall. Here again, finding a publisher was not easy, a big French publisher who does street art books told me – and I quote – “I don’t think a book is necessary. It would have been better if you had illustrated the existing fables of La Fontaine”. Fortunately, other publishers are more open to creation, but it’s always strange to receive this kind of answer. It reminds me that every project is a battle and that it is never, but never, won in advance…