The aim here is to propose a sociological look at war, as well as at our ways of documenting the world. This contribution is thus part of a broader reflection that questions the ways in which war produces and conveys its own imagery.

I made the images for the “Here, There” project in March 2022 as part of a research stay in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. They are part of a new fieldwork and long term investigation in this part of the Gulf.

From the beginning of the twentieth century, while photography transformed our representation of the world, military technological progress transformed the theater of operations into a place of exploration.

In continuity with my research on the modes of fabrication, diffusion and reception of information via the circulation of images produced by war (see HAS #03), I propose here to deepen my reflection on the limits of representation and the gaze we have on this type of imagery. The automation of the modes of image production have transformed technologies into the active subject of war, where weapons also become tools of perception and vision. The artificial eye of these machines blurs the perception of reality, and we can then ask ourselves: what do we see, how and where?

The arrival of drones on the battlefield, among other new technologies, has marked a major turning point in the place of the combatant on the ground. The vertigo of technology now joins the vertigo of terror, where a new apprehension of space and its dimensions is built.

At the same time, the simultaneity of the diffusion of war images between what is happening on the ground and what we see via the information that is disseminated in the media and on social networks means that we are now living the war in real time. We receive information directly in our pockets, on our smartphones.

Already with the Vietnam War and throughout the seventies, the fighting is more and more “mediatized”. With the mobility of the camera installed under a drone or on a missile, a form of simultaneity between the visual of the image and what it records in real time is also developed. The movement of the image induced by the movement of the camera concretizes a form of militarization of the view.

Being far away, seeing close up: the drone

Derived from the translation of the English word drone which means ” false-bumblebee ” or “purr” (of an engine), the term drone designates, in French, “unmanned aircraft”[1] in the air, on land or underwater and piloted remotely. In military jargon, they are known as UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) or Unmanned Combat Air Vehicles. These “new generation” machines are not considered as piloted machines in the same way as planes or helicopters.

UAVs have become an important intermediary in the transmission and collection of information on the ground, allowing data to be processed in real time by the presence of operators on the ground. The evolution of their use has also followed the evolution of conflicts in recent years and they have become a combat vehicle with unprecedented autonomy capabilities. Originally focused on reconnaissance, intelligence and surveillance missions, drones have gradually become “flying, high-resolution video cameras armed with missiles.”[2] Thus, in the absence of a pilot, these machines can proceed in a war context, with the vulnerable bodies[3] out of range. It is a question of lengthening the distance with the enemy, in order to be able to reach him without being reached in his turn.[4]

The first drones designed for reconnaissance missions appeared during the Vietnam War. The Americans used them to detect the presence of Soviet ground-to-air missiles. In 1973, the Israelis used them during the Yom Kippur War to “deceive” their enemy. Present on the ground during the 1991 Gulf War, it was not until the conflicts in ex-Yugoslavia, Iraq and Afghanistan that the drone fully demonstrated its aerial observation capabilities.[5] As for the first killer drone, it made its appearance in 2001. The Predator, conceived in 1995, only became a killer in 2001 during an experimental test during which American army officers took the initiative to equip it with a missile.[6] A new weapon was born.

The automation of the shooting of these machines also sees the management of the data resulting from this new type of images being modified. The devices put in place by these digital technologies induce a distancing of any human presence, until now necessary for the production of images. Whether it is from the point of view of data processing, of the diffusion of images or even of the mode of shooting, the total automation generated by such visual devices disrupts our relationship to the world and the way of representing it.

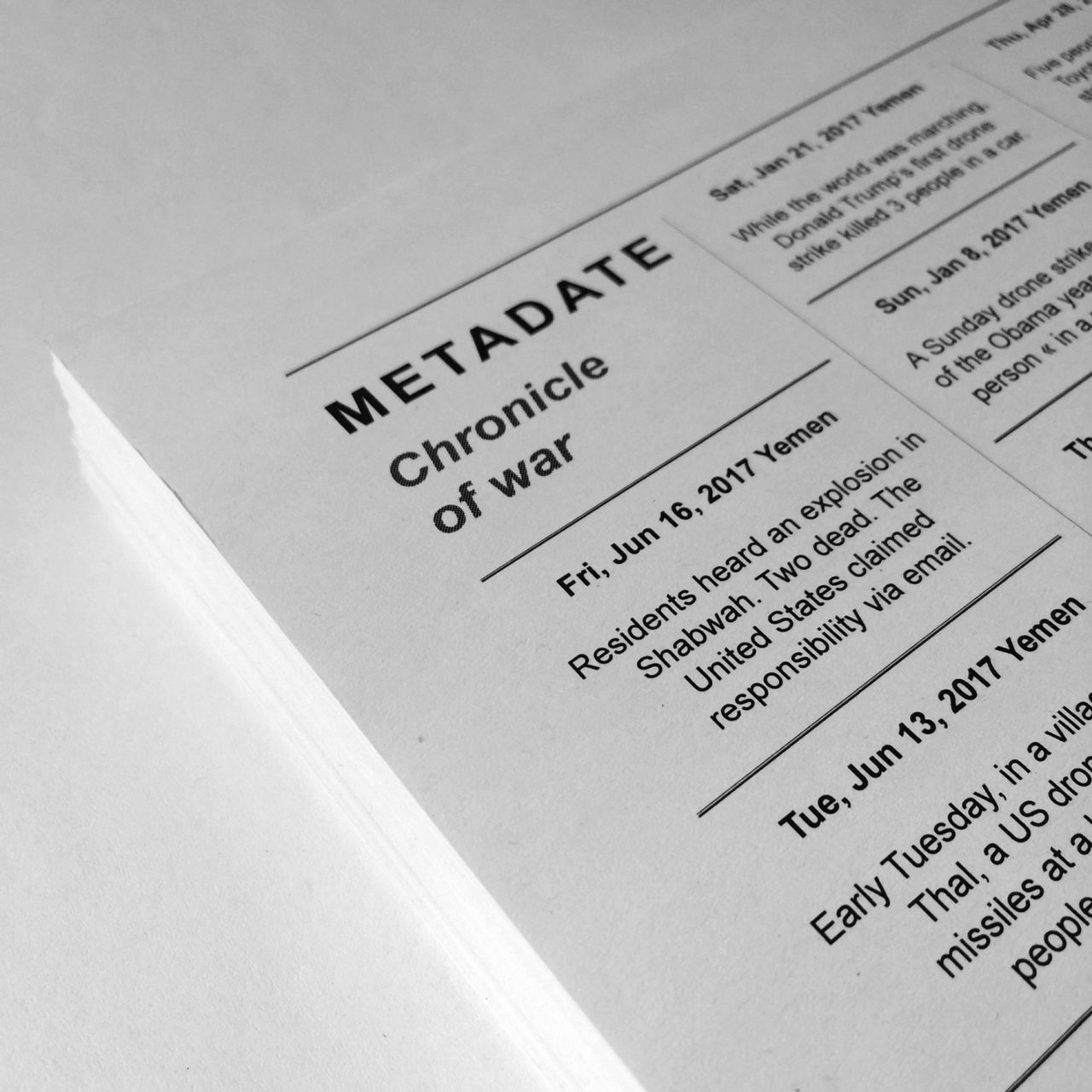

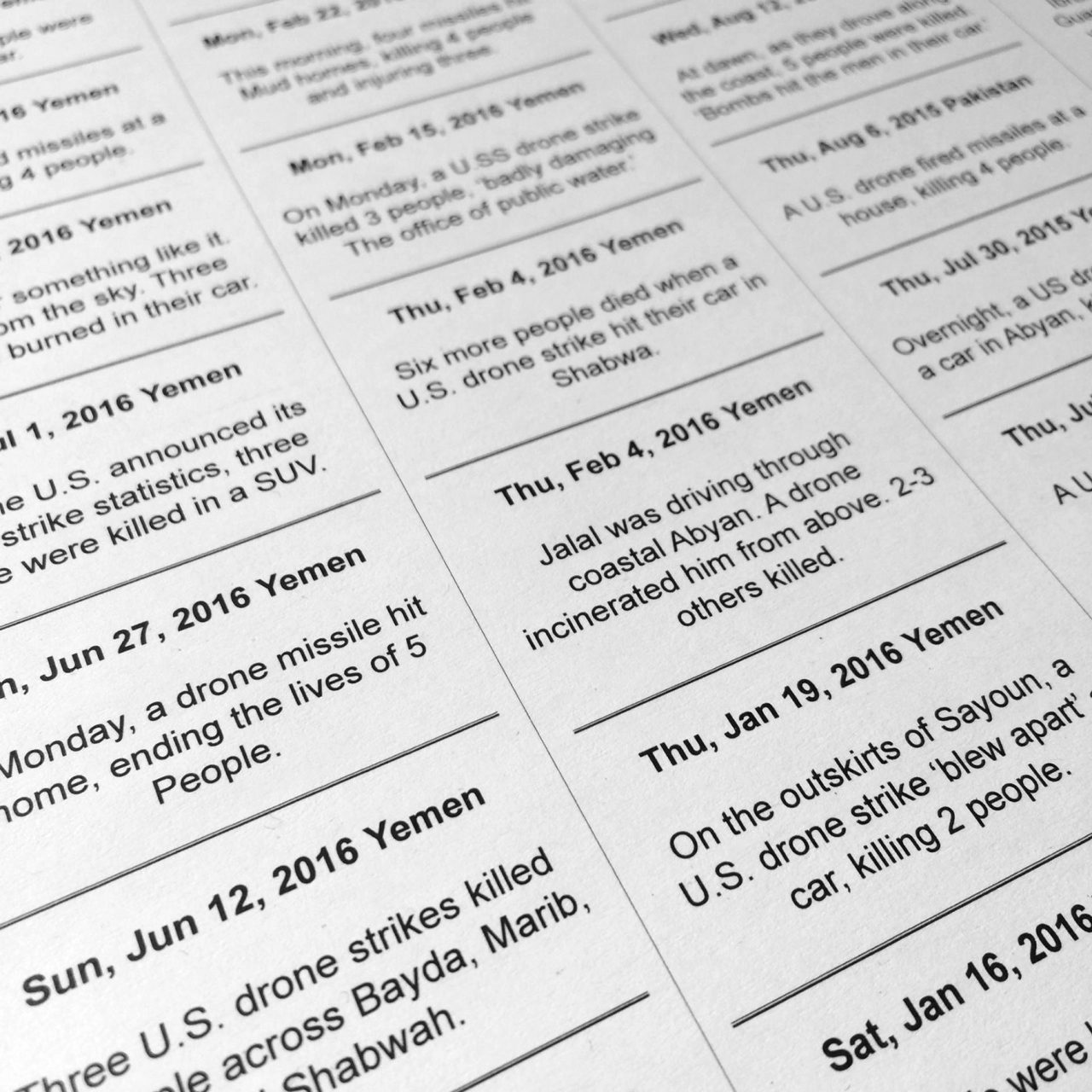

« METADATE – Chronicle of war »

In 2012, American digital artist Josh Begley developed an iPhone app, METADATA+, which tracks U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. Rejected many times by Apple which called Begley’s project “excessively objectionable or crude content,” the app was finally authorized in 2014, after a two-year wait. Based on data from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, every time a drone strike takes place in one of these countries, the app’s user receives a notification informing them of the location of the impact and the damage caused. He can then access a map, which archives all the strikes that have taken place since 2002. I had downloaded this application in 2017 (but it seems to have been deleted since), in order to archive all the drone strikes recorded by the application, in a decreasing manner, between June 16, 2017 and November 03, 2002. Presented as such (see images below) the information transmitted by the application was particularly chilling, and unambiguous, and seemed straight out of a real time obituary column, that of our contemporary world.

Today, images of war are seen remotely in real time; there is a simultaneity between analysis and intervention. To represent the equivalent of a war, it is an image in an office that we are shown. For example, the famous photo by White House photographer Pete Souza, taken in the Situation Room on May 1, 2011, during Operation Neptune’s Spear, which led to the death of Osama Bin Laden. It shows the majority of the presidential staff in a state of extreme tension, following live the intervention taking place in Pakistan. The photograph shows us that they see, but we do not see what they see. With the arrival of drones on the battlefields, war is now played out “at a distance”, and this seems to be the characteristic of modern warfare.

Drone pilots are based outside the combat zone, usually thousands of miles away, but paradoxically, they are located only fifty centimeters away from their control screens. Screens that have often been assimilated to video game screens, and yet the optical proximity between the pilot and the battlefield is omnipresent: it is equivalent to the distance between the eye and the screen.

Could conflicts be thought of from a distance? In any case, these new representations of war allow us to envisage an increasingly constant de-realization of conflicts, where it would be precisely a question of “escape representation”.

War in real time

During the Vietnam War, some teams of U.S. Marines waited for the arrival of the television channels to launch the assault, the camera thus becoming an extension of this mechanized death, and would fix immortal traces of it. Moreover, the war photographers who where embedded[7] to the theater of operations had a certain freedom and could choose the way they wanted to treat the conflict, the photographer’s body was an actor. During the Iraq war :

“Photography has gone from the autonomy of the photographer to the authority of power and forced authorization. Bureaucracy protects power at the expense of the subject who examines it. Images and truth suffer. A photograph is merely the end product of a general system.”

While

“for the Vietnam War, this final system was composed of the body and mind of the photographer, the body being free to move and circulate as it wished and could, the mind being dependent on the personal and often quite flexible and shifting ideology of the subject.”[8]

The Vietnam War was the first conflict where the presence of journalists allowed for a retransmission of the war, and a testimony of it through the broadcasting of images of the battlefield. This media coverage of the battle on a global scale, unprecedented in a war context, alerted American public opinion, the first to be concerned by this conflict. The Vietnam War was contemporaneous with the television revolution and, as a result, the war entered Western homes, with its images of suffering and death. The war became real, present, and the flow of images of violence that the “mass media” began to convey became increasingly difficult to accept for the populations. Television “brought the war into the living room”, in the words of McLuhan.[9] One could no longer perceive war in the same way as previous generations. To a purely analytical approach of the images of war, to the counting of the American victims, was added from then on an emotional approach of the events, raising within the public opinion of the anti-war and pacifist protest movements. Again according to McLuhan, “The television war has meant the end of the dichotomy between civilian and military. The public is now participant in every phase of the war, and the main actions of the war are now being fought in the American home itself.”[10] With the first war against Iraq, in 1991, we witness, for the first time during a conflict, the instantaneous retransmission of images taken directly from the head of the projectiles, by “filming bombs”.[11] This new kind of images, recorded in black and white and showing, most of the time, only the aiming reticule of the weapon, “served only for the photographic control of the effectiveness of the attack. “[12]

“The aerial shots, which were actually only meant for the eyes of military technicians, were supposed to encourage TV spectators to empathize with the technology of war. But we still remain political beings capable of communicating with each other, criticizing images and indeed differentiating between the first war, in which Kuwait was attacked and annexed by Iraq, and the second Iraq war.”[13]

In this war, the freedom of photographers is almost nil: the photographer is “only” the one who operates the camera, then carried by the armored vehicles, which also carry weapons. It is from this war that the concept of “embedded” journalists made its appearance in the Western armies. Described as an “invisible war” by Jean Baudrillard, it conveys the idea that live images of the city of Baghdad and of the actions carried out by the coalition “[…] deliver nothing. Here, the image never delivers anything, we never see the “surprisingly violent resistanceˮ, and even a general shot of Baghdad during the bombing does not clearly reveal what has been hit, or what the consequences will be.”[14]

If a shift has indeed taken place from weapons first conceived as tools of destruction, to weapons that become tools of perception, it is also because “for men at war, the function of the weapon is the function of the eye. “[15] As a result, images no longer function in the same way: the primary function of the image produced is no longer intended for a human being.

« Here, There »

The permanent use of drones in contemporary conflicts, the visual data they generate, as well as the simultaneous recording and dissemination of this information, lead me to rethink the use of these technologies traditionally specific to the military field. I based my research on the Gulf region, and particularly on Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq, three countries mainly involved in the 1991 conflict, a war whose visuals produced something new and unprecedented in the perception and, moreover, the understanding of the conflict, but also of those that will follow.

Infrared technology provides a good example of a perception tool capable of influencing the gaze. A technique from the beginning of the 20th century, originally military, infrared only met a military need because the photographs were only intended for operators. It was used by the army during the First World War to improve aerial photography on glass plates, for landscape mapping. Images that evoke a thud, infrared images have the ability to derealize reality, and delude our relationship to space. Where are we?

By working on places that played a major role in the 1991 Gulf conflict, my project “Here, There” questions the day and night surveillance of a territory, the obsession with control in our contemporary societies, the abyss of the infinite exercise of power. At the crossroads of purely scientific observational photography and disturbing special effects, the rendering of this process transforms places into luminescent and ambiguous settings beyond what, a priori, is made visible.

More and more, our relationship to the visible and the invisible is disrupted by technology. There is no more day, there is no more night. Between fiction and reality, the informative technological image remains just as unreliable today as it was in the days when we were looking for trickery. Where darkness comes to reveal and make visible, as to give to see an image, it is henceforth by the light that darkness is revealed. The flash of Hiroshima, blinding light, had imprinted the eternal shadow of bodies on the stone. Today, it is the power of techniques that illuminates the world that gives itself in spectacle.

Footnotes

[1]. Patrick Ehrhardt, « Le renseignement aérien piloté a-t-il encore un avenir ? », in Bulletin de documentation, n°521, décembre 1997, p. 67.

[2]. Cité par Grégoire Chamayou, Théorie du drone, La fabrique éditions, Paris, 2013, p. 22. « L’expression est de Mike McConnell, directeur national du renseignement, cité par Bob Woodward, Obama’s War, Simon and Schuster, New York, 2010, p. 6 », note from the author p. 316. (see the English translation A theory of the drone, by Janet Lloyd)

[3]. Ibid., p. 23.

[4]. Ibid. See « remote warfare » processes, note from the author p. 317.

[5]. Les drones, tome 1 : « Mieux connaître les drones », published by l’ONERA, Recherche aérospatiale, Chatillon, 2004, p. 5.

[6]. Grégoire Chamayou, Théorie du drone, op. cit., p. 45. It was a Hellfire missile AGM-114.

[7]. More than one hundred and fifty war correspondents died there.

[8]. François Soulages, « Monstrations et expositions photographiques des violences », in Montrer les violences extrêmes, sous la direction de Annette Becker et Octave Debary, Crepahis éditions, Grâne, 2012, p.47. (English translation by the author)

[9]. François Bernard Huyghe, Quatrième guerre mondiale : faire mourir et faire croire, éditions du rocher, Mes- nil-sur-l’Estrée, 2004, p. 162.

[10]. M. McLuhan, Q. Fiore, War and Peace in the Global Village, Bantam Book, 1968, p. 134.

[11]. Term of Klaus Theweleit.

[12]. Harun Farocki, Films, Théâtre Typographique, France, 2007, p. 125. (English translation by the author)

[13]. Harun Farocki, « Le point de vue de la guerre », in Trafic, n°50, été 2004, p. 452, text delivered on October 15, 2003, to celebrate the opening of the winter semester, at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (Karlsruhe), at the invitation of Peter Sloterdijk. (see English translation « War always finds a way », translated from German by Daniel Hendrickson)

[14]. Harun Farocki, Films, op. cit., pp.128-129. (English translation by the author)

[15]. Paul Virilio, Guerre et Cinéma I. Logistique de la perception, Les cahiers du cinéma, éditions de l’Étoile, Be- sançon, 1984, p.26. (see English translation War and Cinema. The Logistics of Perception by Patrick Camiller)

Hélène Mutter is a visual artist, researcher and doctor in Art and Sciences of Art. For more than 10 years, her approach is at the crossroads of artistic work and theoretical reflection on the social construction of the gaze on war. Multidisciplinary, her work unfolds in the manner of a long investigation that combines research and fieldwork that question, more broadly, the ways we have to think about the representation of our time and our society. She recently went to Saudi Arabia to begin a new long-term project in this part of the Gulf.

Hélène Mutter is a visual artist, researcher and doctor in Art and Sciences of Art. For more than 10 years, her approach is at the crossroads of artistic work and theoretical reflection on the social construction of the gaze on war. Multidisciplinary, her work unfolds in the manner of a long investigation that combines research and fieldwork that question, more broadly, the ways we have to think about the representation of our time and our society. She recently went to Saudi Arabia to begin a new long-term project in this part of the Gulf.