Digital Reading: Historical Roots

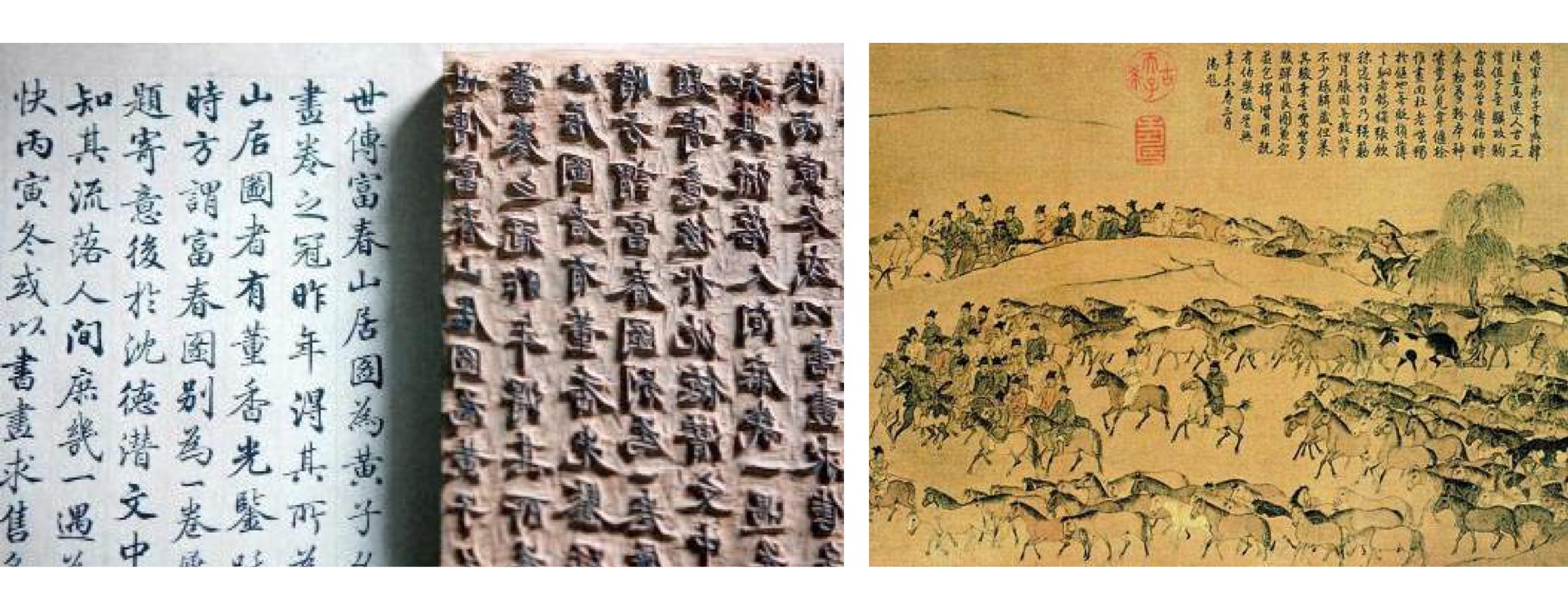

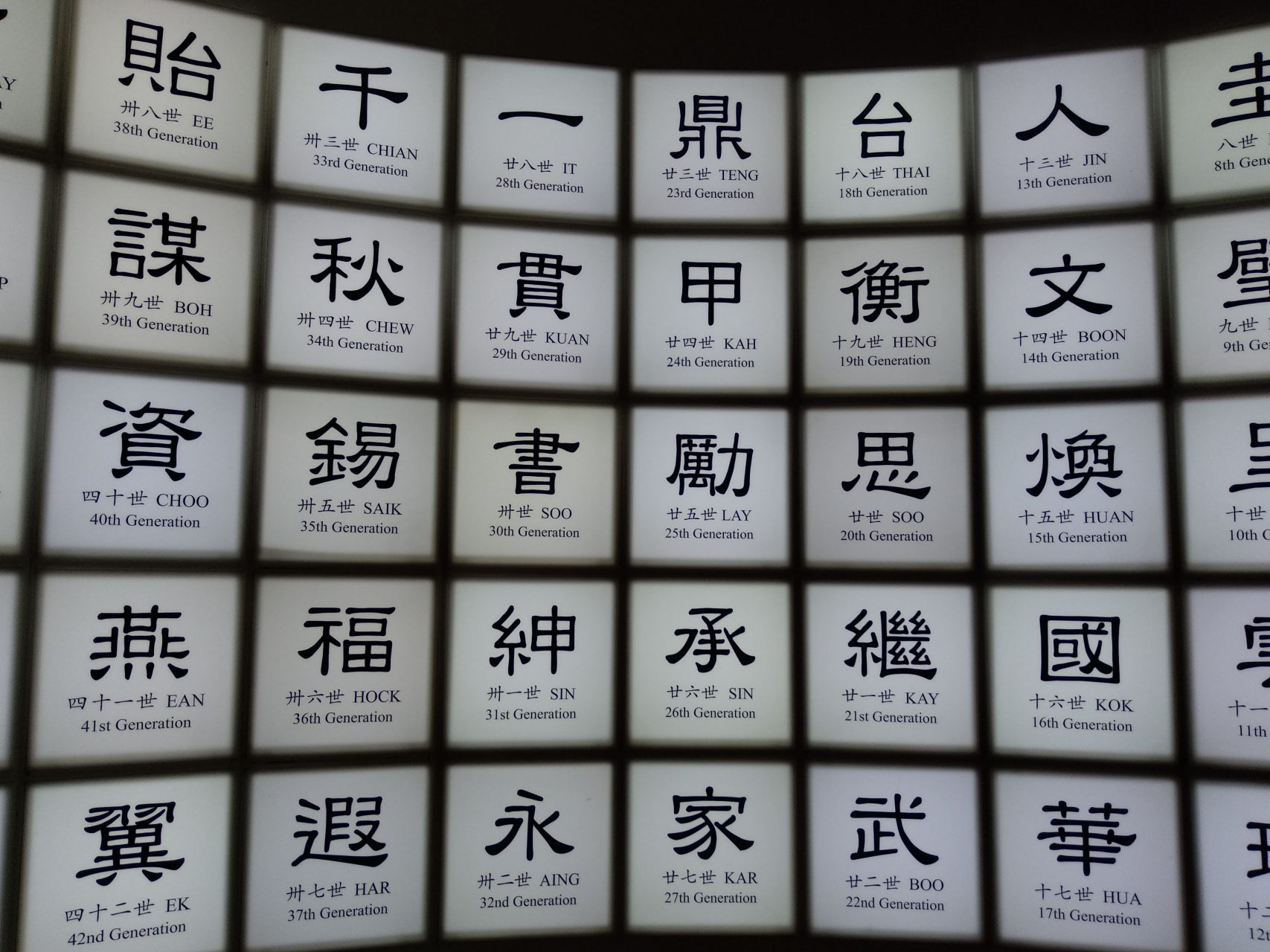

Some scholars have assumed that online literary activities are but one step further in the technological revolution of print culture, which historically provided the technical means to create a mass audience, speeding the spread of information and flattening class distinctions. Print media liberated the non-elite, empowered women, dethroned authoritarian literati officials, enlarged the demographic base of information-sharing, and unleashed the power of ordinary men and women. In Chinese history, this began in the eighth century with the invention of woodblock printing, followed by the gradual spread of print culture from the Song to the Ming dynasties.1

Is the logical next step the rise of internet literature and digital reading, which has brought over eight million authors and up to 200 million readers? These numbers are undeniably historic, with respect to both production and consumption. If numbers speak, the market is the only objective measurement for “truth” in human development. But is it? Or should it be?

There is no question that access has been a critical determinant in gaining the power of knowledge. In terms of availability and readership, first of all there has been the problem of becoming literate, after which there remained the question of gaining access to the world of letters, especially in the days when the formats for the written word were mud blocks, bamboo strips, or hand-written compositions in brushwork. Back then, popular culture was a subject of serious concern, because technology, not just autocratic politics, monopolized the circulation of information.

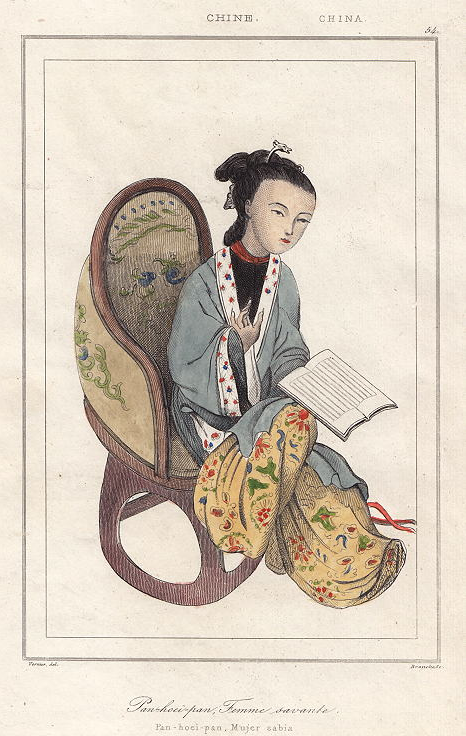

With the advent of print culture and its ability to rapidly duplicate and reproduce messages, print material, folded into leaflets or bound into volumes, was being carried by shops in cities and towns. This was the great equalizer, the socio-political instrument that empowered the reading public by taking the authoritative control of information away from the ruling classes. Informative and satirical prose collections, novellas and dramas, pungent and hilarious stories, were widely circulated. Even women, who were not supposed to be studying the classics, did so anyway, alongside their brothers, indulged by their fathers and uncles. Women even composed and published commentaries, albeit using their husbands’ or brothers’ names. That is what access to information enabled.

Now, as the statistics illustrate, internet literacy has moved society to its next stage, via digital reading and writing. Though diehard conservatives and old-fashioned elites continue to read on paper, there is no denial that a page has been turned without everyone’s consent or participation. People only need to observe their children or grandchildren to realize that many, many more now read by following lines on a screen, than turning pages by the movement of a finger.

Sociologists tell us that all-male internet reading groups existed before women created their own digital reading clubs, the emergence of which prompted the internet company Tencent’s purchasing and creation of what is now the Yuewen Group on the Hong Kong stock exchange in 2003. Italian, French, and English literary historians tell the same story about the appearance of the novel as a genre, emerging on the European cultural stage to meet the demand for reading material by curious, educated, and affluent urban women seeking pleasure in their leisure time. Printed books and the literary form of fiction needed to be there to meet their needs, not to mention writers eager to please them, rewarded by fame and wealth.

We may view authors on the internet literary market with a similar perspective. Its ostensibly market-driven character carves out a convenient escape, if you will, away from restrictive political surveillance, as the pleasurable nature of most of the content, called “cultural entertainment,” offers a mutually accommodating haven, a semi-cultural reprieve from this moment of transition. The danger of subversion from a social force that is undermining from the bottom up may become palpable as long as the in-your-face threat is transformed into drop-by-drop amusement, eased by the soft, laughable plots of tedious, trite episodes about love and hate.

But what about public duty and the moral order that people say should always come with information and literacy?

The Evolution Of Internet Literature—A Chronology

Though much about the surfacing of Chinese digital literature remains debatable, the fact remains that it is a singular phenomenon, unlike any other in the world of cultural production and literary consumption. Depending upon how you count, this phenomenon exploded onto the cultural stage within the last four years, counting from May 2017, when Yuewen went on the Hong Kong stock exchange, or 17 years, counting from October 2003, when fee-based internet reading provided the first business model. If, as the proverbial saying in Socialist China goes, the market is the only measurement for truth, there is obviously something to be accounted for here.

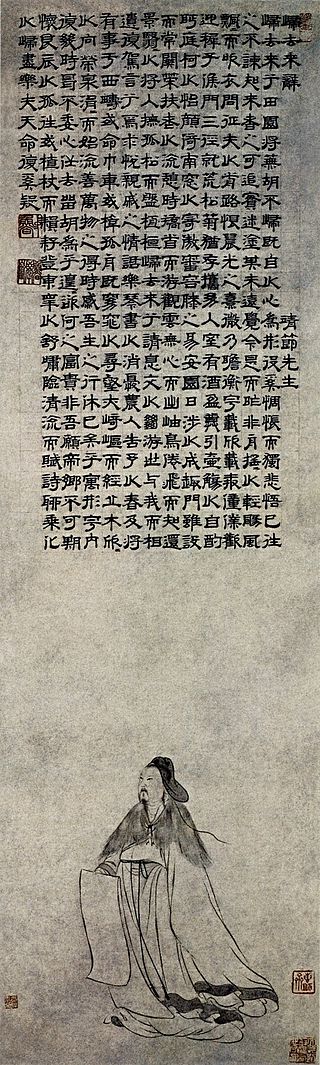

Two features of the internet literature in China stand out—one substantive, the other sociological. Examining its content, one cannot fail to recognize its roots in the traditional literary genre of the strange and fantastic, a genre that goes back centuries in Chinese storytelling and readership, to the Wei-Jin or Six Dynasties’ Tales Of The Strange. Unbelievable stories circulated in towns and villages, crossing boundaries between the unreal and the believable.2 Petit-bourgeois dilettantes earned a living by jotting down suspicious stories for the growing market for commercial literature following the Song Dynasty, which mushroomed by the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in the Ming.

Strange Tales From A Chinese Studio is the best-known example from the Shandong province, where old stories of fox spirits falling in love with poor civil service students attracted many listeners, whether they believed them or not.3 By the high Qing era of Qianlong, even Ji Xiaolan, the Chief Editor of the Imperial Complete Library In The Four Branches Of Literature and the highest highbrow under heaven, could not resist the temptation of jotting down odd tales, leaving behind his Notes From The Thatcher Hut Of Reading The Imperceptible.

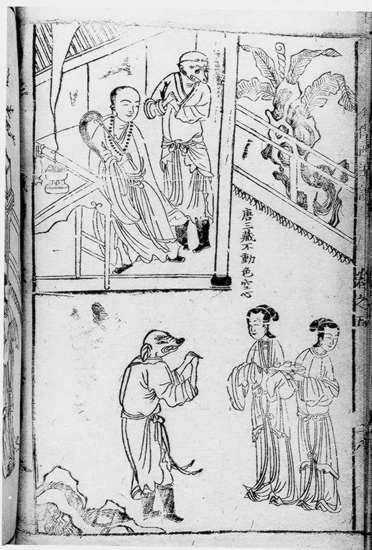

Even if one were to skip the sprawling development of the martial arts thrillers of the late Qing to early Republic, Chinese readers’ taste for the fantastic in period settings is still notable, hardly mitigated by forces of modernity. One need go no further than the Monkey King in Journey To The West 4 by Wu Chengen (1506-1582) to see that here lies a cultural reservoir ready to overflow, taking with it the audience for children’s stories, animation, television, and cinema. This literature requires no initiation or education. You do not even need to read (or be) Chinese to appreciate it.

The women’s readership that provided the market base for Shengda Internet Literature to go commercial in July 2008, was the critical business moment which eventually led to Yuewen Digital Reading. For literary historians, it adds evidence to the familiar story of gender as the factor that gave literature its “modern” aspect. The novel did the same thing for nineteenth-century European literature, emerging on the English, French, and Italian literary scenes.

If one were to add a third cultural-political perspective to the historical significance of the internet literature of the early twenty-first-century Chinese writing-and-reading scene, it would be the liberating character of internet technology. It guarantees a bottom-up, interactive immediacy and, in the current Chinese context of economic transformation, it can hardly be held back or contained by any force. It has staged a cultural explosion that has stormed the market, and requires no other legitimacy. It throws readers, authors, editors, managers and producers into a state oblivious to the politics surrounding them.

Old Romance Novels Go Viral

Those familiar with late imperial Chinese culture know that literature embodying the tastes of the petit bourgeoisie in the Song cities and towns exploded with the late Ming print culture in the sixteenth century. The stories were often based on the oral tradition of storytelling, in its vernacular form, closely associated with theatrical performances, amusing the highbrow as well as the low.

Two sub-genres capture the essence of this literature: the Romeo and Juliet type of love stories epitomised by The Story Of West Chamber, The Peony Pavilion, and Dream Of The Red Chamber on the one hand, and the Robin Hood type of martial arts stories such as Romance Of The Three Kingdoms and The Water Margin. Both are part of traditional Chinese romance literature. Often with an element of the fantastic, these stories uncovered the dark side of society seen in government bureaucracy, righting wrongs and answering social outcry. Earlier admiration for the knight-errant with marvellous martial-art talents combined well with mythological characters carrying magical spells. Tough heroes with soft hearts, sympathetic to the weak and needy, became the trope of martial-arts romance literature, one to which many remain addicted.

One final literary touch needs to be added to complete the full picture of early modern Chinese literary taste— the sequential chapter style of market-town storytelling. Most of the aforementioned narratives consisted of 40 to 80 chapters, many with another 40 or more trailing after. Fans have grown an unquenchable thirst to follow the tales regularly, step by step, over an extended period of time.

These literary tastes were taken to the next level in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in decadent, glamorous Shanghai. From the 1890s to the 1910s, magazines and newspapers in the vernacular language like Saturday Weekly or Good Compassions Pictorial provided the venues. Out of 36 such publications, all but one were from Shanghai. They were popular and commercially successful, providing people with entertainment at an affordable price. Though criticized by high-minded scholars and May Fourth intellectuals such as Zhou Zuoren or Qu Qiubai (1899-1935), these critics could hardly suppress the public appetite.5

They carried the essential genes for the going viral one century later, on the internet, when Chinese society and the mainland economy offered them the perfect environment to take the main stage of popular literature.

The Creation Of A Reading Habitat

The Chinese reading public that includes the 1.5 billion of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, plus the over 60 million of the Chinese diaspora, have not only inherited the realms of romance and martial arts literature that go back centuries, but also a narrative style that is intrinsically sequential. The subject matter also tends to fall back on inherited topics—dynastic transitions, courtesan struggles, palatial treasons, dark intrigues, and factional fights, in which traditional medicine, sectarian religion, Buddhist and Taoist monastery entanglements and popular beliefs mingle as familiar parts of Chinese life. The post-war era among the overseas Chinese in Taiwan and Hong Kong continued to feed a growing multimedia market which moved from the Shanghai cinema of the 1920s and 30s, quickly taking on television in the 50s and 60s, then the worlds of games and e-sports—a path serial literature in Europe or America never travelled.

Questions can continue to be asked about whether the charms of the Chapter Novel and its continuation in the sequential publishing of modern magazines and newspapers was what did the trick. But the problem is that the modern literature of Europe and America succeeded in most of the above, but fell short of catching on or cashing in as it did in China. Why?

The reading habits nurtured by the episodic storytelling tradition in Chinese literature trained their followers to be accustomed to the unfolding of drama in daily episodes. Opening with a short introduction to sweep in new audiences, addressing their fans as “you folks,” they did a trick in between chapters that the daily newspapers and magazines picked up. The never-ending storytelling tradition was to keep their listeners and readers addicted, so that if wanted to find out what happens next, you had to listen to/read the next episode.

How else can we account for the reading habits created by this form of story-telling? Social imagery going as far back the telling of strange tales in the third century carried both the consumers and producers of Chinese popular literature through the vernacular stories of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the dramas of the Yuan (1279-1368), the print culture, performing arts, and travelling theater of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911), sprawling during a time span too long and a socio-cultural void too immense, it appears, to be backtracked.

Other theories have to be ventured as to why monumental literary creations like The Arabian Nights, or the phenomenal novels of nineteenth-century European literature—Madame Bovary (1856) in France, Anna Karenina (1875) and The Brothers Karamazov (1871) in Russia, or Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) in America—did not create a similar habit of reading and authoring. All of these novels were originally published as serials in the magazines and newspapers of the early modern era, though they admittedly were not episodic in compositional style.

The cultural production scene of 1920s and 30s Shanghai witnessed fiction publishers selling rights to the budding film industry. Questions need to be asked as to why there was such a booming market for the post-war martial arts and romance storytelling, which might just reveal a closer link to the digital era and the post-reform development of internet literature in contemporary China.

Afterthoughts

Internet literature clearly created new pathways to reading and additional venues for learning, further enhanced by the continuous lowering of the age group of the reading public in the digital era. So-called digital natives—an ever-younger generation of internet users who have grown up technologically savvy—get both information and gratification via electronic means, almost from birth. Through this reading habit, the critical element may not be conviction but familiarity and convenience, which has been made undeniably easy by internet technology and the digital market. Even though it is criticized as wasteful extra-curricular activity and non-educational indulgence, contemporary Chinese youngsters worldwide are getting their information by electronic means. Hundreds of millions of Chinese readers are fed by the internet, whether this is approved of by society or not. Their numbers and the duration of their user time continue to grow—a fact made blatantly evident during the public lockdown and social isolation of the pandemic.

Content analysis and the structural study of viral internet literature nevertheless shows that romance literature, martial arts stories, and fairy tales continue to capture peoples’ attention, in the cultural products of animation, television, and cinema as well as in literature. The old habits of following sequential narratives contribute to the pattern of the phenomenon in no small measure. This presents a potentially alternative view about truthful beliefs served by poetic justice, and the development calls for respectful attention paid to the cognitive significance of internet devices as new venues of learning, for better or worse.

Notes

1 Licille Jia and Hilde De Weerdt, eds., Knowledge and Text Production in an Age of Print: China, 900-1400 (Brill, 2010); Cynthia Brokaw and Christopher A. Reed, eds., From Woodblocks to the Internet: Chinese Publishing and Print Culture in Transition, Circa 1800 to 2008 (Brill, 2010).

2 See Xiaofei Tian, “From the Eastern Jin through the early Tang (317-649)” in Kang-I Sun Kang and Stephen Owen, eds., The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature Volume 1 (Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 199-285; Robert F. Campany, Strange Writing: Anomaly Accounts in Early Medieval China (State University of New York Press, 1995); Mu-chou Poo, Ghosts and Religious Life in Ancient China (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

3 Judith Zeitlin, Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale (Stanford University Press, 1993). For translation, see John Minford, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (Penguin, 2006).

4 For translation, see: Anthony Yu, The Journey to the West, 4 vols. (University of Chicago Press, 1983, 2012)

5 For an account of modern Chinese fiction, see: Chih-tsing Hsia, A History of Modern Chinese Fiction (Yale University Press, 1961; 3rd ed., Chinese University Press, 2016).

Hsiung Ping-Chen is Secretary-General of the International Council for Philosophy and Human Sciences ( CIPSH) – and CIPSH Chair in “New Humanities”, University of California, Irvine.

Hsiung Ping-Chen is Secretary-General of the International Council for Philosophy and Human Sciences ( CIPSH) – and CIPSH Chair in “New Humanities”, University of California, Irvine.