Anxiety and hope are both nourished by imagination. They are the result of our history as much as our environment, which—through repetitive external stimulation, information, and prophecies—can sometimes induce a lack of security that shakes the very foundation of our being, and at other times can bring joy, enthusiasm, and comfort. Anxiety is all around—it whispers in our ear and narrows the space within and around us. It lays its vast veil of confusion over our blinded gaze, an object-gaze of anticipation in which the subject becomes the object of its own projections, the shadows gain a body, and the body turns to shadow.

Hope opens up all that is possible. We project ourselves into paths, accomplishments, and solutions that broaden our horizons, widen our gaze, and restore movement and multiplicity to the future as well as to our thoughts. It implies trust in that which emerges, changes, or is maintained. It counteracts the anguish of loss and death.

Hope And The Present

Anxiety manifests itself in the way we use objects—digital objects, physical activities, cultural objects, work, nature, health. When these objects are limited to affording a release of tension, they act as outlets, leaving little room for any alternative or longing. The object is consumed, the subject is consumed. In terms of our interpersonal relationships, this release can manifest itself as overly seductive behaviour, but as soon as it fades, it gives way to more creative ways of interacting, to a reciprocity that transcends the encounter and gives hope.

The primacy of visual imagery in so-called modern societies carries with it certain ideals that bind the individual to a game of incessant and anxious catch-up with themselves. The ideal is not intended to be achieved, but if it is too far removed from reality, it generates—on both the individual and collective scale—a feeling of powerlessness, discouragement, exhaustion, even despair.

And yet, hope is only here. Here. In the present, in the space of the here and now. It is now: I am writing. It is later: You are reading. It is at all times and never more. What relates the present to hope?

The present is the possession of our readilyavailable psychological, sensory, and motor capacities—now, in the present time we inhabit. This possession is, however, always relative. It can be encouraged by favourable contexts, and it can be optimized if we manage to create the internal conditions needed to use them, provided we are not hindered by our health (let us note that in the case of disability, the presence of the other plays a major role). Our nervous system connects us to our perceptions and to our sense of feeling, within our own context and in the precise moment we are living. Our body is here—it informs us of what we feel.

If hope lies within this psycho-sensory present, then the methods and actions that bring an individual closer to themselves, and therefore to self-awareness in the present, must contribute to hope.

The development of somatic techniques illustrates this well—the Feldenkrais Method, Body-Mind Centering, Eutony, Holistic Gymnastics, the practices of Ehrenfried and Bartenieff, to name a few. Having appeared in Europe and North America between the 19th and 20th centuries, these techniques consist in using movement and internal physical perception to develop awareness of one’s being and the way in which one interacts with one’s environment.1

Creation As An Emergence In The Moment

Let us consider Indian meditation techniques before the emergence of Buddhism in that country,2 as well as neuroscience in the West. The practising of concentration and awareness enables a proximity to sensory perception, emotional phenomena, thought processes, and the subject’s resonance in the moment. The relaxation methods developed in the 20th century in Europe and the United States, based on yoga or hypnosis, are part of this approach—such as Autogenic Training and Progressive Relaxation.3 We can also mention Sophrology’s multifaceted approach.4 Each of these practices offers the chance to reconnect with our bodily experience through deep muscular relaxation, generating mental rest that can at times even include an existential dimension.

Finally, the creative act also plays a part. Whatever the artistic field in which it expresses itself, particularly when it exists for itself regardless of any exterior expectations, the act of creation is an emergence in the moment. Perceptive and sensory acuity, the expressive movement, reveal the uniqueness of the creative subject within the time frame of their experience of being, which, in the here and now, is always new.

If we refer to Edmund Husserl’s phenomenological approach,5 which evokes a body made of flesh and experience, we sharpen our self-awareness in the present through our sensory perception. By calling upon the bodily experience and the mobilization of our attention toward it, we gain access to the vast field of multiple and subtle sensations we can respond to in order to sustain, modulate, or change a given situation. Retaining such power over ourselves, we are also capable of using it on our environment. We are constantly sculpting our clay through a dialogue between the self and the world.

These experiences also imprint images within us—impressions which can revive a memory from our past and even mingle with current perceptions through an overlapping, or even confusion, of time. These reminiscences, both authentic and legitimate in their emerging psychosomatic reality, involve a movement of return—a return of the past, of similarity and, it would seem, even a return of sameness. And yet, much like the present moment, the experience of the body—the thinking, feeling, moulded-by-history body—is always new.

The uniqueness of every moment suggests that plasticity is plausible and that renewal is always possible. In order to access this novelty, we need to identify the sensory quality and the very nature of our feelings. The psyche does not respond to fixed, linear logic, nor is it hermetically closed off from new information, provided it be in sufficient contrast to be perceived. The task at hand is to choose non-routine methods of differentiation, mediation, and guidance in order to tap into the acuity which is already present in our nervous system. This sometimes includes the presence of the other as a witness of a shared present. In the case of the creative act, the artwork itself plays the role of the “other,” reflecting back to the creator the original tones of his expressive gesture. Far from sterile repetition, we are here dealing with consecutive novelties. Accepting the singularity enclosed within them creates hope.

Between Hope And Anxiety

As individuals, we each have a unique history made up of a series of events which have shaped us through their impact on our emotions, and through the symbolic interpretations—or lack thereof—that we assign to each experience. This shaping of the self is influenced by the environmental conditions in which we have evolved. Regardless of our individual will, the mechanisms and contents of our thoughts, emotional processes, and actions testify to the activity of our unconscious mind and its influence. The body carries the mark of this in its posture, habits, and functioning.

In order to be able to hope, it is necessary to re-establish the notion of choice, which is only possible through first perceiving the field of possibilities. We can attempt to extract ourselves from predictions, and from our tendency to stage reality through the projection and rumination that are specific to anxiety, by reducing the excessive psychosomatic stimulations which saturate the functioning of our nervous system. This cognitive commotion and sensory cacophony can also be brought on by our environment, which conveys a lack of security that can be conducive to the most potent forms of anxiety (collapse, annihilation, death) and push us to withdraw from the world. Taking action over anxiety’s somatic manifestations allows us to experience a tangible space of action that is within our reach.

There are several psychotherapeutic approaches that aim to outsmart the unconscious mind’s tricks and anxiety’s patterns. Beyond the therapeutic approach, let us now consider sensoriality and sensorimotricity as possible pathways between anxiety and hope. Somatics, meditation, and creative work, whether practised in the fields of healthcare or in everyday life, create hope, not because they are close to a socio-cultural ideal of how human beings should be in the face of political and economic violence—extreme self-control, composure, forceful yet calm at all costs—and not because they echo the stereotypical idea of bliss based upon a vague interpretation of oriental wisdom by an often misguided and exoticism-seeking West, which moreover has now turned it into a commodity.

These practices generate hope because the individual, by being able to pay attention to themselves, by listening to what they feel, and by observing themselves, train themselves to exist within a present without the need for imitation. Gaining clarity, the subjects become capable of seeing beyond their habitual ways of perceiving and feeling. By learning to lower their muscular tone and their nervous excitability, the subjects offer themselves the possibility for more diverse and less impulse-driven action and thought. They develop an alert awareness and, being less impressionable, are able to make enlightened choices. They allow the unprecedented to arise within themselves and open up horizons in places they once felt trapped.

The creative act also carries within it certain psycho-sensory elements that sharpen the perception of the creative subject in the moment. In their quest, the subjects face a series of trials which, beyond their apparent repetition, whether they serve a conscious or unconscious purpose, lead them to find something within themselves.

The Unexpected

The habitual aspect involved in our gestural behaviour, meant to make the execution of our daily tasks easier, comes at a cost, and can easily turn into automatism. The illusion of sameness lulls us into an impression of repetition which can shape us, paralyze us, and sometimes even numb us, cutting us off from our sensations. Does the passing of water, running endlessly over the rock, dig a single furrow, forever dictating the path for future water? The furrow makes a trace. It acts as a guide, it invites, but despite its influence, it does not claim a monopoly. It humbly bears witness—its presence is reassuring, inviting, cradling.

In his teachings, Moshe Feldenkrais insists that the accomplishment of any desired action, including the ability to change one’s way of doing things, depends upon one’s awareness of one’s own action.6 Consciousness of action cannot forego subjectivity. Subjectivity exists through it and can be interpreted, understood, known. Feldenkrais proposes experimenting with new, unusual bodily postures in order to undo the numbing effects of routine and familiarity.

When we speak of the present, we are therefore speaking of consciousness. From the latin cum and scientia, it is the knowledge of what is relative to oneself, and in our case, to the sentient self. By knowing where we stand, and by drawing on what we feel, we can shape and hone the use of our selves, thus acting as true authors of our actions and deepest intentions. From there, we can lessen and even suppress the actions we carry out against ourselves, often feeling regret, as if victimized by them. We can open other avenues.

In the extreme case of psychic fractures, such as traumas which can powerfully freeze feelings in time, a therapeutic approach is necessary, particularly with regard to so-called “unassigned experiences.” However, the search for self-awareness in the moment remains valid in that it offers a way out of the fixation of time so as to access “the after,” meaning “the present,” or in the case of ongoing traumatic experiences, to access that which bears vitality in moments which bear death.

Finally, let us consider the hope lodged in the unexpected—the well-known serendipity of the seeker who examines the “here” only to find the unexpected has emerged elsewhere. Relaxation and channelling thought through acute sensory and perceptual feeling creates availability. Far from a magical phenomenon, it is an aperture toward that which may arise, and a willingness to welcome it. Let us consider the works of the Surrealists, which give rise to spontaneous, thought-less creative action, and from which arise novelty, wonder, the unexpected and… laughter, which is so closely related to hope.

That which occurs within the intimate space that is the body has repercussions in the social body. The former is our tool to thwart the consequences of the unthought known.

Hope is rooted in our sense of being. If we fear death, then we must nurture that which sustains life. Trials and experiences of the self are a pathway to hope and to refusing fatality—”sense, feel, act.”7

These creative approaches aim to overcome the injunction of being by welcoming that which arises in the present, as a witness and a creative subject. They respect our tendency to choose reassurance when faced with anxiety, without drawing any conclusions, allowing us to go beyond the initial quest for relief and security.

Tranquilly, regaining power over oneself through introspection, knowledge, and re-connection, is the opposite of violence—etymologically translated as the extreme force exerted upon something or someone. Discovering one’s potential for action with regard to oneself and one’s environment is to calm anxiety—which is self-ignorance in disguise—and regain not only hope, but also faith in one’s existence and that of the world.

Vertigo

No clashes on the brim or the gap. The body of the world unfolds here.

It all starts with the eye. Next comes the mouth, the hand, the ear, the skin, then the entire cellular orchestra. From fragment to whole, the shift is subtle.

Step by step, we make our way through the maze, pulling up the veil, exposing the face. A smooth and head-on walk.

Scarcely have we crossed the threshold, a whirlwind of contradiction snatches us away from reason. Sideways, upside-down and across, beyond the reflection, from the horizon line upturned, from the opposite side of the face, downside-up of the duality, before what mirror, through what prism and whom to believe? Oranges are bananas, green is blue, empty is full. Breezes or gusts of absurdity carry with them the alien melody that comes looking for us.

No need to struggle. It’s a game, we play. Let’s stay in the eye of the storm and unclip the phalanxes.

Letting go.

It’s so dark around here. To seek the calibre too much, one becomes blind

to it.

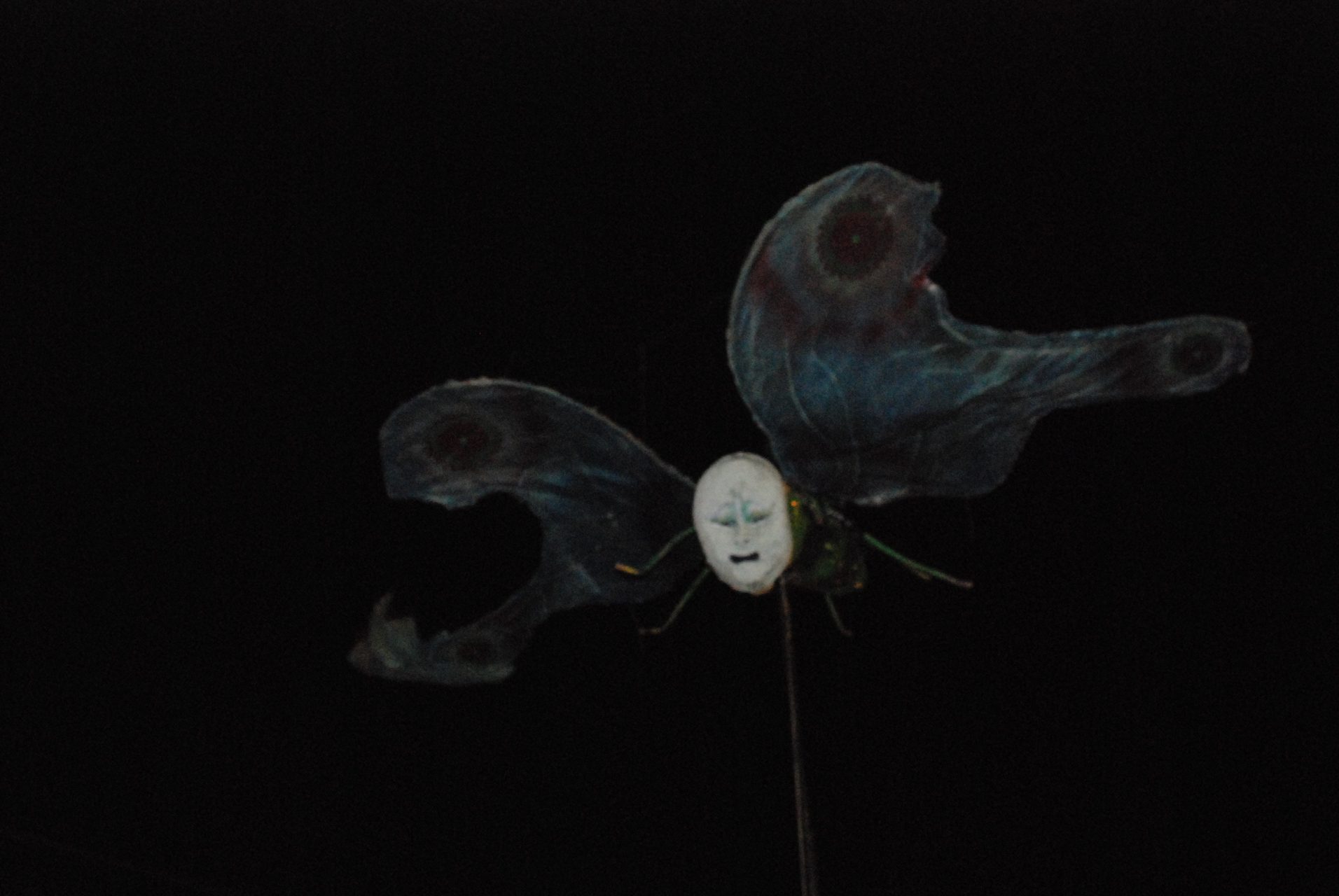

Help me float away, take me into the delight of mistakes, the mirth of trickery, the cunning of bewitchment! Fool the eye, fool death in this infinite dream defying the theorems. I take a smoke bath at the risk of drowning. Ghosts, snake charmers, pay attention to us, because in our deliberate vulnerability, we bet everything.

Who will believe that we saw glory here on stage singing her spectre?

Drunk on directions, deformed with contortions, clouded by thoughts, letting go again. It does not take much: an orb movement, a slight rotation of the globe, not even a twitch or a flicker, rather the drift of an eye.

We drift to reach the mirage. We drift to reach the miracle. You drift to emerge beyond reason, to tear your back, freezing, from the wall, because from the unfathomable darkness is born the deadly vertigo. It aims at us, yes, it aims at me, at you and implores you to give meaning and depth.

From this shade devoid of any reflection, this dreadful abyss, this extreme chasm clothed in velvet, at last you are born, a clay statue. Artwork made of argil.

At the risk of rain.

The Night Before the Forests,8 we walk across the land of cistus, without punctuation. Cistus grows with rage and zeal on the burnt land. Always a foreigner, he is crying out. He magnifies desire. In the face to face, one on one, his cry strips modesty bare, tears off its clothes and throws up fear. The violence of the call screams love. Unknown in the mouth. A flood of saliva keeps the alien at bay. This taste, hinted at in the corner of the lips, already slips away, question mark on the tongue, quickly, to absorb the juice, to relish the vanishing elixir, to spit out the meat.

Still we walk.

In the garrigue, creatures made of flesh and emotion become heady with scents until unearthly hours. Along mystical and secret paths, the myrtle adorned with a silk haik makes his entrance.

He embalms, permeates, raptures.

Impressionist landscape of sapphire and opal, surreal feeling of celebration.

A festival of roots; pistils and stamens in a tango, calyxes dancing round, a farandole of grapes, corollas blooming: we are here in the land of Cockaigne. The mischievous thyme is exhaling. Concealed, he is picked up by the handful. Untamed rosemary openly blossoms; how tall and exuberant we feel next to the kermes oak, bush of everlasting childhood. The wild madder exalts her red; the lustful honeysuckle embraces the hummingbird moth. A frenzy of leaves and thorns swarming around carves deeply into the flesh, cutting through any fabric that is now spun, caught, or holed. Around us, the rock is breathing. We can hear her.

She tells fossilized stories here and there, crazy tales of sea spirits still babbling in the cavities at nightfall. A limestone book, big as the universe, opens before us. A manuscript with a chiselled binding, mucilage as its embroidered linen and sediment words upon which the algae, swirls of jade, morph into eagles or dogs.

At the edge of the cliff, a cave.

The bedrock invites us into the bath of Artemis: the lady of wild beasts will dance here tonight to the sound of the drum. On its white-hot skin, the presence will resonate, in refracted waves, in persistent echoes.

Dangling beauty.

In the land of cistus, we shall gaze.

- Education Somatiqe France

- Eric Rommeluère, S’asseoir tout simplement. L’art de la méditation zen, Paris: Seuil, “Sagesse,” 2015, 160 p.

- Dominique Servant, “La relaxation : nouvelles approches, nouvelles pratiques,” Issy-Les-Moulineaux, Masson, Pratiques en psychothérapie, 2009, p. 175.

- Académie internationale de Sophrologie Caycédienne

- Edmund Husserl, Les méditations cartésiennes. Introduction à la phénoménologie, Paris: J. Vrin, 1966, p. 136.

- Moshe Feldenkrais, La puissance du moi, Paris: Editions Marabout, “Psychologie,” 2010, p. 303.

- Bonnie Bainbridge-Cohen, Sentir, ressentir et agir, Brussels: Contredanse, “Revues Nouvelles de Danse,” 2002, p. 367.

- Bernard-Marie Koltès, La nuit juste avant les forêts, Paris: Editions de Minuit, “Romans,” 1988, p. 64.

Adeline Voisin is a clinical psychologist with degrees from the University of Lyon II in psychology with a specialization in inter-culturality and from the University of Lyon I in clinical criminology and physiology. She is trained in dance therapy and relaxation techniques and she develops art and body therapies for psychiatric institutions. She is the founder of Surf Art Trip that offers experiences to immerse oneself in the natural environment of the ocean coasts, the creative act and one’s own body.

Adeline Voisin is a clinical psychologist with degrees from the University of Lyon II in psychology with a specialization in inter-culturality and from the University of Lyon I in clinical criminology and physiology. She is trained in dance therapy and relaxation techniques and she develops art and body therapies for psychiatric institutions. She is the founder of Surf Art Trip that offers experiences to immerse oneself in the natural environment of the ocean coasts, the creative act and one’s own body.