© Carla Della Beffa TimeLine, 2016

In dialogue with

TimeLine

by the artist Carla Della Beffa

This article presents a reflection on the Humanities’ contribution to the development of more inclusive and just perceptions of care, which was initially delineated through a semantic development which proposes an understanding of the concepts care, justice, and perception in its reverse sequence. In the next step, the curricula of some higher education courses in Portugal were partially analysed, from the perspective that the curricula can be a practical expression of a humanising action established by this movement.

Caring. Justice. Perception. The terms that introduce the present text show a semantic movement created by different forms of comprehension. The inverse sequence of terms—the specific proposition of this investigation—shows the colours of a horizon to be expanded throughout this article—Perception. Justice. Caring. It is here that the semantic development occurs, and will be narratively presented through the interaction with human and political sciences.

The introductory frame is based on inversion—a route that shows humanitarian actions, aiming at the fair perception of caring for oneself and for the other. The route of inversion is an invitation to the reader. Each term of this route reveals features of the same horizon, the interpretation of which demands the hard work of the attentive researcher in contact with the urgencies and challenges of present times.

Perception

The contextualisation of contemporaneity, expressed by the force of the transition between the 20th and 21st centuries, is vital to potential investigations. Anthony Giddens, a British sociologist famous for his Theory Of Structuring, is one of the authors inspiring this discussion. In his writings dating back to the 1990s, Giddens reflects on what he had previously called society of classes. Since then, the author has used the term Modernity, which characterises the ways of life or social organisation of Europe in the 17th century, and which has progressively reached the global scenario. The consequences of such modernity are perceptible in the present century, even though unexpected transformations have taken place.

(Authors’ Image)

According to Giddens, the change from traditional society to modernity presents emblematic conditions—the reduction of time-space relations, which creates new agendas, and a unique type of reflexivity, through which the modern person gets in contact with excessive flows of information involving him/her. In other words, the modern world is a world on the run since the pace of change is notably faster than that of systems in force in the past. Moreover, transformations have become increasingly fuller, and characterise the dynamic character of modern social life.

From the author’s perspective, an important advance is the split of time and space. Somehow, all cultures have their own way of organising themselves in time and space. In pre-modern contexts, for instance, time and space seemed to be associated and, as such, favoured conditions of existence that were apparently predictable. Nowadays, time and space, in a continual process of social distancing, cause new expressions of individual and collective life. In the same way, the typical organisations of modernity cannot exist without a new integration of time and space. Under such conditions, modernity is, in essence, a post-traditional order, with modifications in time and space that generate “updated” configurations of social life.

In his work, Giddens shows significant changes in societies since the 1960s—so-called globalisation, late modernity, radical modernity. In a certain way, the author no longer considers the long history of modernity, but the recent and relatively brief history of its radicalisation. Next, two characteristics of the process described by Giddens also illustrate the scenario for research in contemporary times.

Globalisation and tradition. The world of the 21st century is a scenario of individual and communal relations under tension. Local events can be conditioned by other events which, combined, reach the global sphere. The most obvious cases are common in economy. Still, the growth of electronic communications media, which instantly promote exchanges of information over the planet, must be considered. Such factors develop the social relations of the places where institutions are established, and strongly influence the daily lives of people all over the world. As to space, radical modernity consists of individuals uncomfortable about the places where interactions take place; as for time, radical modernity is noticed similarly through a sense of liberation, through a vague sense of belonging to tradition.

Reflexivity. Giddens emphasises the semantics of this term to address the ways in which individuals behave within the context of radical modernity—or reflexive modernity. In the same way, reflexivity is associated with the person who chooses one or another type of practice, one or another project of life, influenced by a lot of information, references, resources.

The scenario created by Sociology contributes to a critical reading about the social environment that illustrates the early decades of this century, filled with unpredictability.

Justice

Modern philosophy has shown growing changes in this century. Its contribution is important, and leads to paths of justice through significant expressions of understanding. In his vast work, the twentieth century philosopher Paul Ricoeur discusses the most profound philosophical tensions of contemporary times. He puts together methodological aspects of different philosophical areas from which emerge phenomenological, hermeneutic, existentialist, and analytical approaches, through the art of an original frame.

(Authors’ Image)

In his work, Ricoeur addresses topics from the problems of will and evil to a hermeneutic phenomenology of the self, through the insertion and performance of the human being in History, by the interpretation of the symbol, metaphor, and action, by the historical narrative and fiction, and by the issues of the ideology of utopia, ethics, and politics. In this sense, Ricoeur considers himself the heir of Husserl, Heidegger, and Gadamer, whose topics and methodological resources are subordinated to one objective—the creation of an ontology of action—a field that, for Ricoeur, remains unexplained according to Tradition traced by philosophy.

Ricoeur presents the horizon of a meaningful philosophy of interpretation, through the articulation of hermeneutics and phenomenology. Such renewal can occur according to two perspectives: (i) as Heidegger did, designated by Ricoeur as the short route of understanding, and (ii) in a more mediated way, which passes through the method—the long route. This is his proposal and personal contribution to hermeneutics and its justice.

Differently from Heidegger, Ricoeur does not intend to challenge the ontology of understanding of the former. However, he considers it necessary to celebrate the approach to an epistemology of interpretation. The epistemological consequence of Heidegger’s hermeneutics (subversive of the Husserlian phenomenology and performer of its first objectives), with its conception of the human being as being-in-the-world is: There is no understanding of oneself without the mediation of signs, symbols. The interpretation of symbols belongs to hermeneutics; however, such an interpretation should not be reduced to identifying symbols, since, with the integration of symbols into texts, it is possible to work out meaning, in “conflicts of interpretation,” as mentioned by the author.

Ricoeur proposes a less immediate route, because the ontology of Heidegger’s understanding seems too hasty—or short—because it implies the impossible direct passage from epistemology to ontology. In fact, access to existence calls for deviation through semantics, so the understanding of symbolic expressions and narratives is not limited to mere interpretation; rather, it constitutes an important stage in the journey taken by human beings in their search for understanding themselves. This movement reveals that semantics is covered with a shade of justice.

Ideally, the subject characterised by the long route does not identify himself with the Cartesian cogito, since the human being realises the understanding of himself through the understanding of texts, symbols, and signs. In fact, in the place of the consciousness of the self, a fuller and deeper self comes in, recognising itself through its actions and achievements. Reflection is manifested, along the long route, together with ontology and hermeneutics, of the self and its expressions.

The philosophy of reflection proposed by Ricoeur includes Heidegger’s ontology. However, it is very different from the philosophies of the cogito—it is not a reflection that starts from scratch and leads to absolute knowledge, it is rather a reflection that contains the consciousness of assumptions. The person that emerges from this point is receptive to caring and inclusion.

Caring

Several descriptions illustrate the sense of caring—for oneself, for the other, for the community. In this discussion, caring for oneself and for the other is considered through narrative-based hermeneutics, which opens unfinished routes of understanding.

(Authors’ Image)

To start with, it is important to make a distinction between the I and the self. The I represents a permanent identity, rooted by the sign, without the mobility activated by narrative; the self reveals a reflexive, personal identity, marked by otherness and narrativity. In fact, the self cannot be aware of itself immediately, but only indirectly through a deviation, prompted by narrative. It is a privileged mediation, which favours the arrangement of fictional and historical elements as a human task of existence. In this sense, the presence and action of men and women of all times create a strong opposition against structuralist expressions that occasionally reduce the text to a set of words and structures.

The narrative force is present in the self, which cultivates a hermeneutics of narrative identity for which the interpretation puts the self and caring together. In fact, caring arises because the human existence is based on community. According to Ricoeur’s expression, “good life”, with and for the other, caring is associated with inclusion, and with a movement from the edges to the center. At this point, there rises an urgency, captured semantically and built up narratively, which will be illustrated in the sections to come.

Curricula as the practical expression of a humanising action based on perception, justice, and care

The conceptual basis and the theoretical-linguistic reflection previously presented show that the notion of care, more than a political-legal concept, is an ontological concept based on the values of human dignity, freedom, and solidarity—that is, a humanistic and profoundly human concept. From this emerging perspective, we will analyse the answers given by the curricula of some higher education courses in Portugal.

The curriculum might be an important vector as an answer to the considerable challenges that humanity faces in the contemporary world, and that are deeply related to the ethical dimensions of respect for human rights and overcoming individualism, in the sense of thinking about the construction of belonging to the human community in a time of multiple technological innovations. It should also be noted that we will try to investigate the possibility of the practical expression of this humanising action of care in this context.

It is worth emphasising that the development of a more inclusive and fairer perception of care involves, among other things, justice and reflection on cultural diversity and the identity of peoples and nations. The insertion of these themes, as well as other, related ones, into higher education curricula might be a significant contribution of education and Human Sciences.

Based on the idea that “the humanities have an essential role to play in equipping societies to make sense of the contemporary challenges they face and enabling governments and other policy-makers and social actors to respond to them” (see the Lisbon Declaration on Humanities, Open Research and Innovation of May 2021: http://www.guninetwork.org/news/lisbon-declaration-humanities-open-research-and-innovation), as well as the importance of interdisciplinary dialogue, we shed light on Humanities in the curriculum, as an educational process based on humanistic perspective. In this sense, the Humanities and the Social Sciences must actively promote the critical spirit, the philosophical and ethical sense of the universal, in relation to the challenge of recovering the ideal of the Organic Totality of Greek antiquity.

This way, the humanities might be included in higher education course plans in a transversal way—which has been a trend in technical and technological areas—or it might constitute a modality itself.

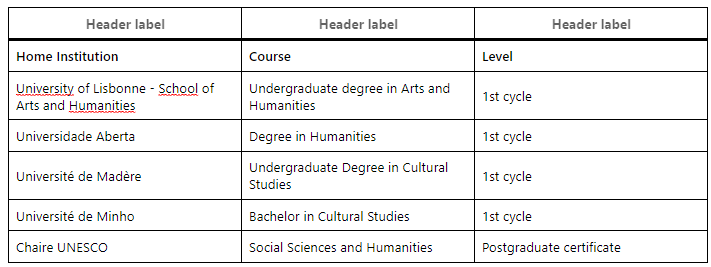

This text will proceed to a very brief analysis of some courses which were chosen for being part of the humanities and culture area—i.e., courses meant to promote the issues of fundamental rights, citizenship, diversity, and identity as pillars in their curricula (Table 1).

(Authors’ Table)

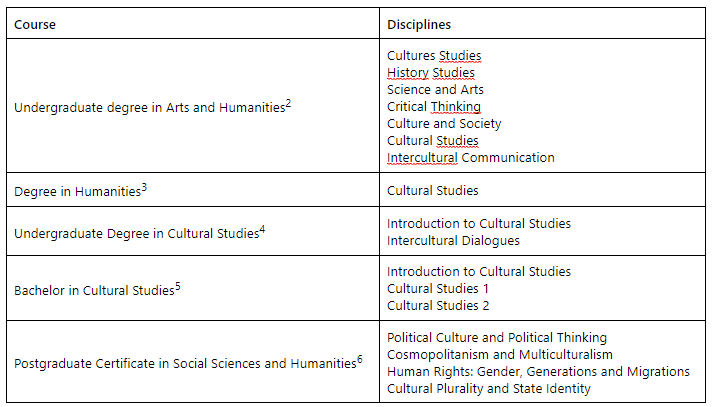

The themes of cultural diversity and identity are inserted into these courses plans by means of disciplines. From this empirical basis, the presentation of the results is organised as follows:

- List containing the disciplines included in the curricula (Table 2).

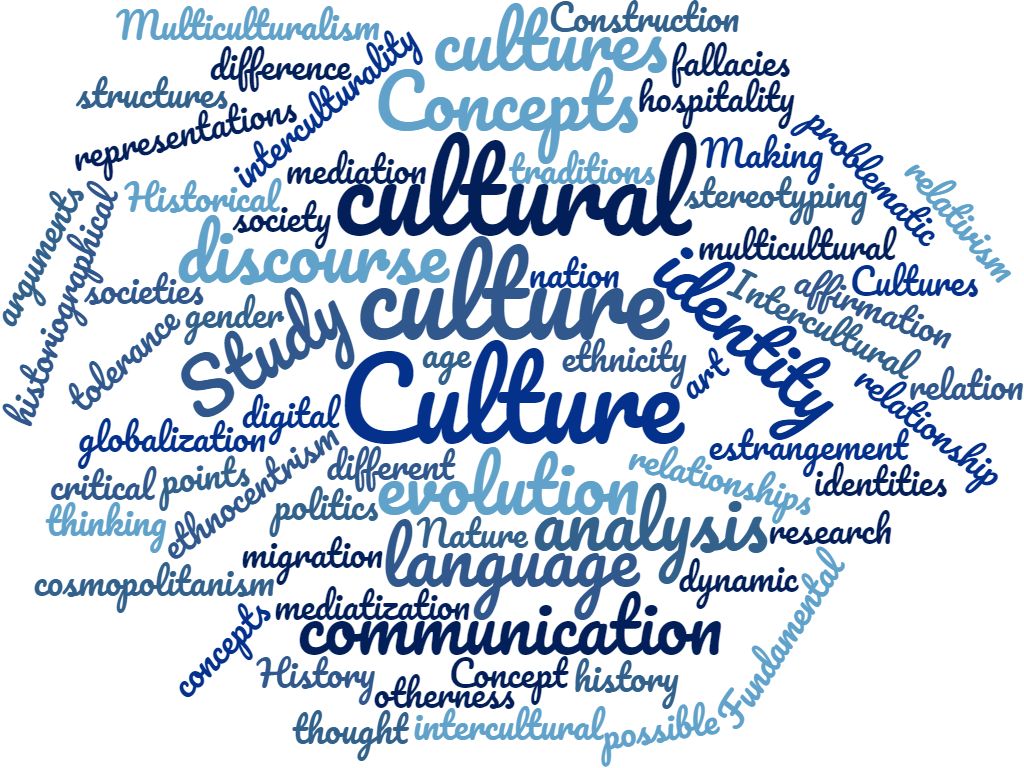

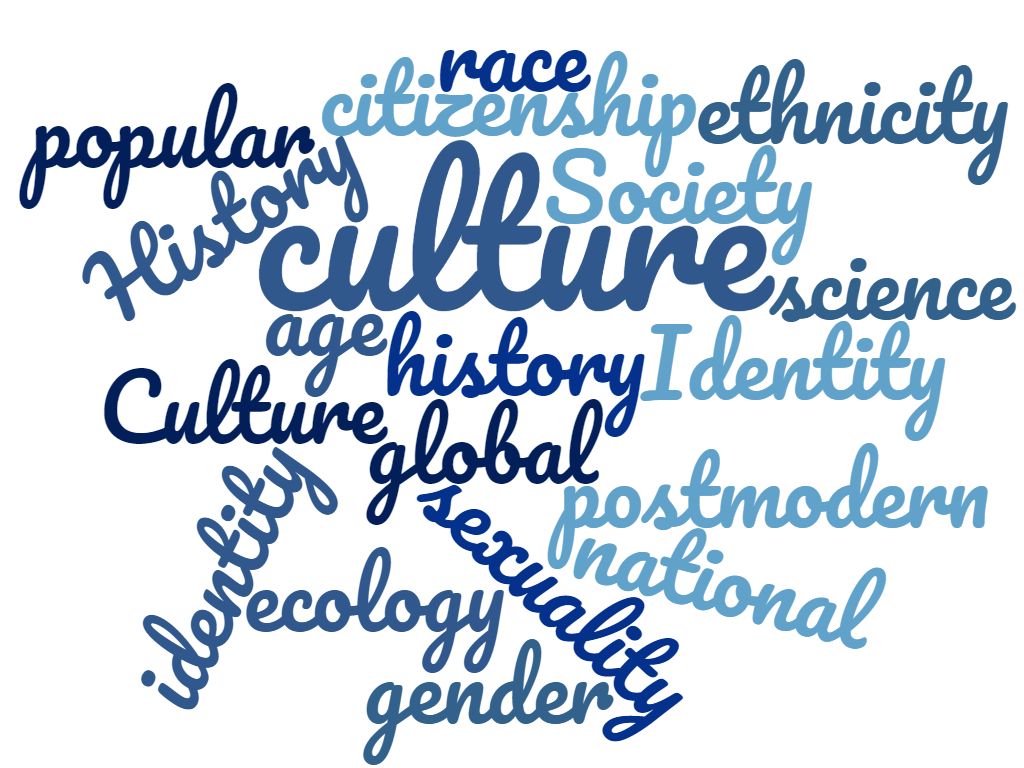

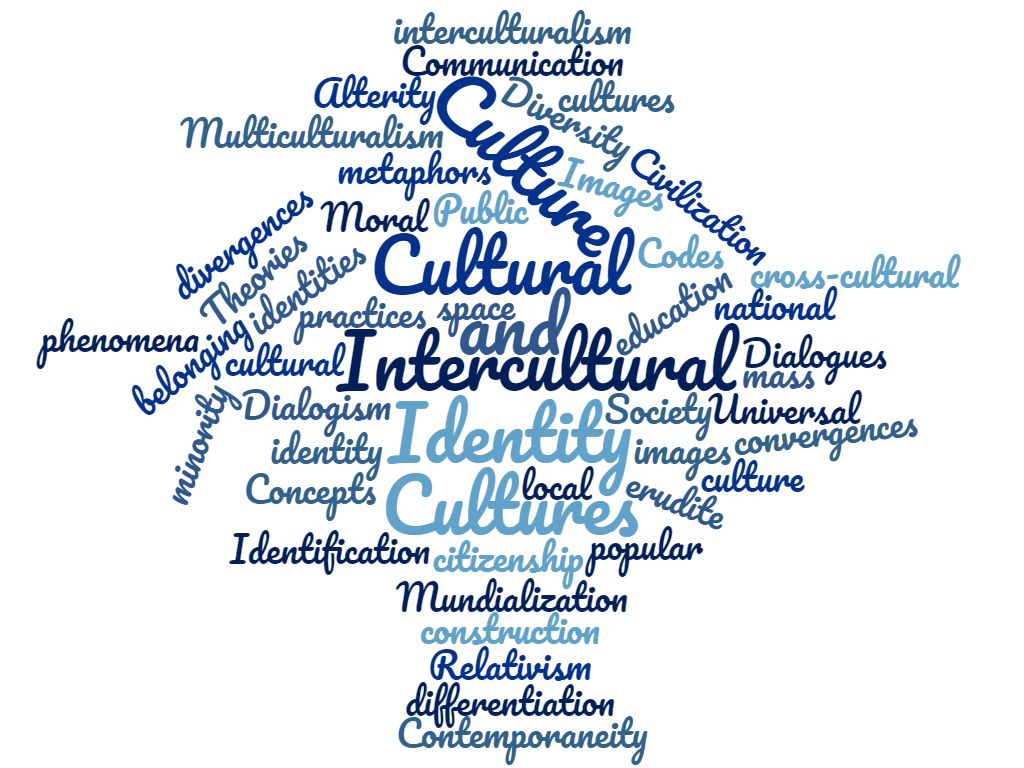

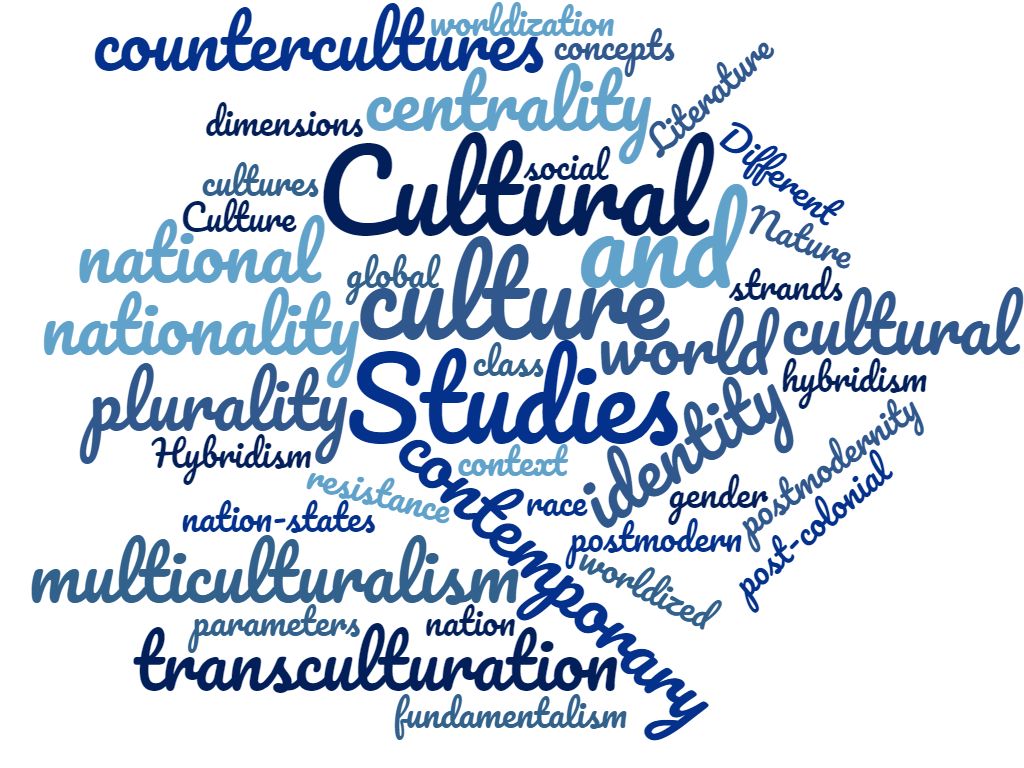

- Program analysis of the same subjects using the word clouds as visual strategy to demonstrate issues which have been privileged in the curricula of such courses.

List of Disciplines

(Authors’ Table)

Word Clouds

(Authors’ Image)

(Authors’ Image)

A higher education course is translated into practice through its curriculum, whose sense expresses the desired society and the citizens that one intends to form. In other words, the issues contained in a curriculum represent a certain worldview to be put into practice.

The word clouds indicate that when dealing with cultural diversity and identity, the themes privileged by these curricula are History, concepts of culture and cultures, diversity, identity, languages, communication, citizenship, race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, interculturality, plurality, politics, contemporaneity, countercultures, human rights, State and Nation. This frame demonstrates that these curricula are crossed by a humanitarian perspective.

In sum, it is possible to argue that the Humanities’ contribution to a fairer and more inclusive perception of care consists of the centrality given by this area to the major issues of contemporary society. Inserting the mentioned themes into the curricula is a political positioning coated with humanistic values, an essential factor for its realisation as fundamental values of Human Rights and grounds for a civilizational construction.

References

1Portugal’s higher education follow a three-cycle structure, leading to the bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and PhD, as well as also has postgraduate certificate courses.

2University of Lisbon. “Undergraduate degree in Arts and Humanities”. https://www.letras.ulisboa.pt/pt/cursos/licenciaturas-1-ciclo#artes-e-humanidades

3Universidade Aberta. “Degree in Humanities”.

https://www2.uab.pt/guiainformativo/planoestudos1.php?curso=61&ma=23

4Université de Madère. “Undergraduate Degree in Cultural Studies”.

https://www.uma.pt/ensino/1o-ciclo/licenciatura-em-estudos-de-cultura/

5Université de Minho. “Bachelor in Cultural Studies”.

https://www.elach.uminho.pt/pt/estudar/Paginas/Licenciatura-em-Estudos-Culturais.aspx

6UNESCO Chair on Education and Science for Equitable Development and Human Welfare (EDUWELL). Postgraduate Certificate in Social Sciences and Humanities. “Guidelines 2021”.

Bibliography

Giddens, Anthony, Modernidade e identidade, Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2002.

Giddens, Anthony, Tutner, Jonathan, Teoria social hoje, São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 1999.

Ricoeur, Paul, O si-mesmo como outro, São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2014.

Ricoeur, Paul, Tempo e narrativa: a intriga e a narrativa histórica (Vol.1), São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2016.

Isabel Maria Freitas Valente: PhD in Advanced Contemporary Studies (International Comparative Studies), Researcher and Professor at the University of Coimbra. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2403-5147

Marcelo Furlin: PhD in Languages. Researcher and Professor at the Methodist University of São Paulo, Brazil. Collaborative Researcher at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC, Brazil). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6282-3721

Eliane Cristina da Silva Nascimento: Master’s degree in Education, History and Philosophy of Science and Mathematics; PhD Candidate in Human and Social Sciences (UFABC-Brazil), research fellow at the Centre of 20th Century Interdisciplinary Studies of the University of Coimbra (CEIS20-UC); Instructor at the Federal University of Technology – Paraná (UTFPR). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8050-3219

Carla Della Beffa lives in Milan, Italy. She is a photo, video, visual, relational artist and writer. She has been drawing most of her life and started painting in 1992. She then went through several phases, media and themes, from net-art to books, each one appreciated somewhere, internationally or nearer home by galleries, curators and other artists, sometime a publisher.

Food, economy, words and relationships are at the core of her work.

Isabel Maria Freitas Valente: PhD in Advanced Contemporary Studies (International Comparative Studies), Researcher and Professor at the University of Coimbra. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2403-5147

Marcelo Furlin: PhD in Languages. Researcher and Professor at the Methodist University of São Paulo, Brazil. Collaborative Researcher at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC, Brazil). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6282-3721

Eliane Cristina da Silva Nascimento: Master’s degree in Education, History and Philosophy of Science and Mathematics; PhD Candidate in Human and Social Sciences (UFABC-Brazil), research fellow at the Centre of 20th Century Interdisciplinary Studies of the University of Coimbra (CEIS20-UC); Instructor at the Federal University of Technology – Paraná (UTFPR). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8050-3219

Carla Della Beffa lives in Milan, Italy. She is a photo, video, visual, relational artist and writer. She has been drawing most of her life and started painting in 1992. She then went through several phases, media and themes, from net-art to books, each one appreciated somewhere, internationally or nearer home by galleries, curators and other artists, sometime a publisher.

Food, economy, words and relationships are at the core of her work.