The Tower of Babel of Eastern culture

On the Eurasian continent, 2000 years ago, the Sogdians treasures traversed Rome, Persepolis, Xi’an, and many other cities across Europe and Asia1. Accompanying the caravans were monks and priests of various denominations, who brought with them not only their religions, but their culture and art.

By exchanging with the local people, the Sogdians mastered and learned about languages and culture, music and art, and their techniques and tools. Through the sharing of histories and customs, and through the action of engagement and contemplation, they accepted each other’s differences, and eventually created an exciting and rich culture.

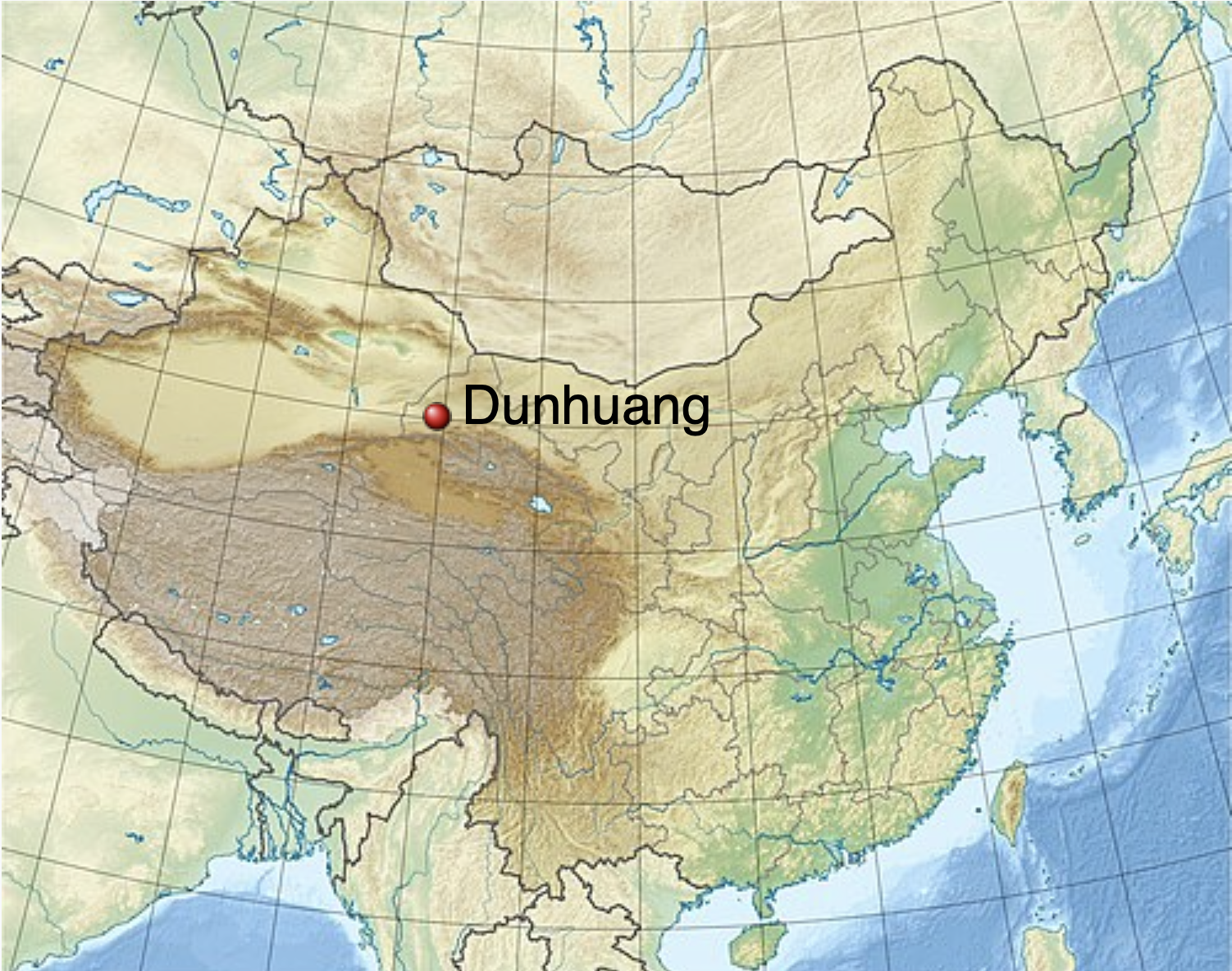

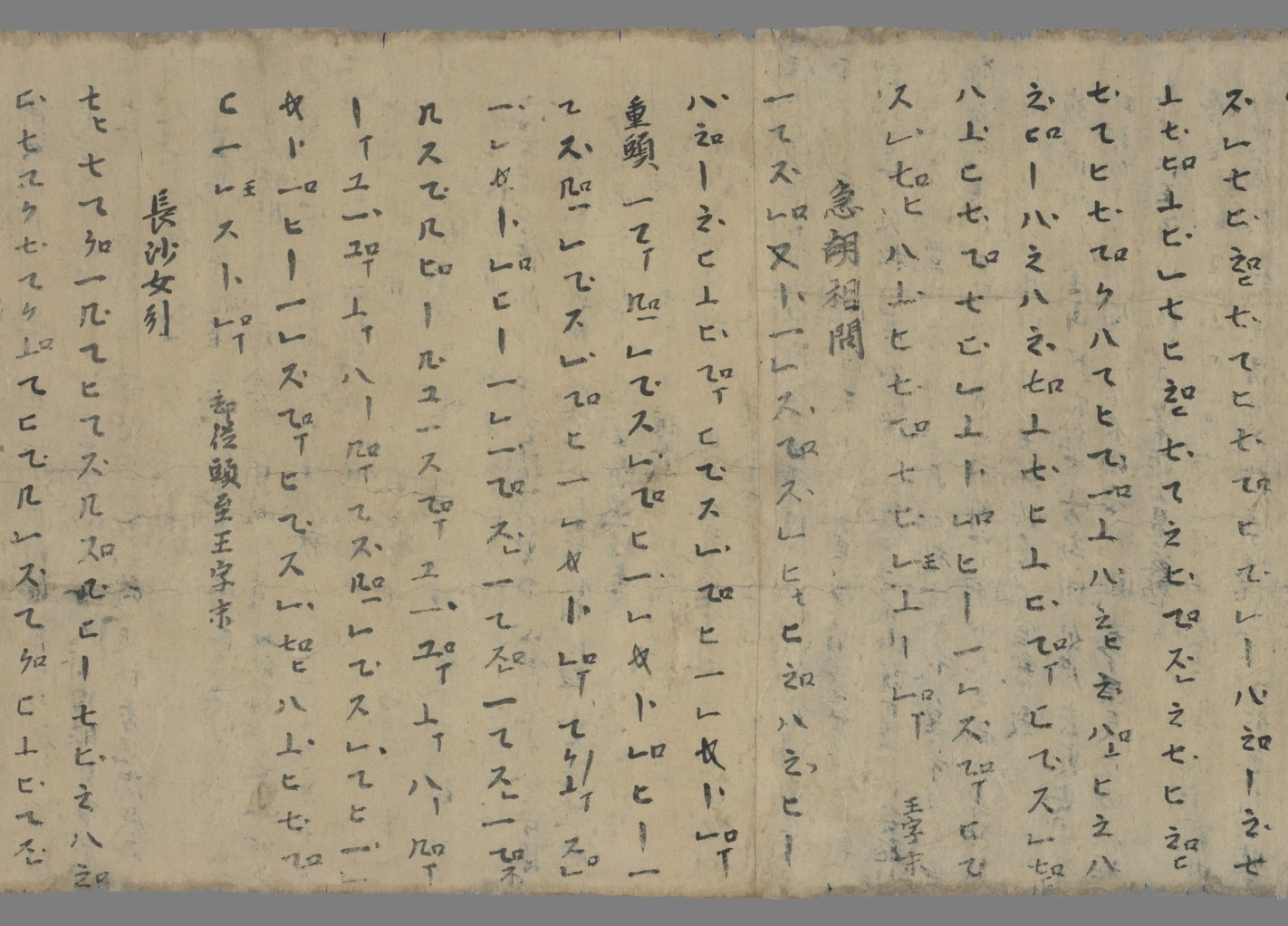

In the second year of Jianyuan of the Qin Dynasty (AD 366)2, the Buddhist monk Le Zun3 roamed through what is today’s Gansu province4. Just before dawn, he saw a golden light shining on the front of the Sanwei Mountain that looked exactly like ten thousand Buddhas, so he dug the first of many caves into the rocky cliff. This marked the beginning of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang (see Pictures 1 and 2)5. Documents from Han, Wusun, Rouzhi, Huns, Xianbei, Sogdian, Dangxiang, Uighur, Tubo, Xixia, Mongolia, Manchu, Hui, and many other ethnic groups are collected here. Nowadays, the site has spawned a special discipline called Dunhuang Studies due to its abundant frescoes, sculptures, scriptures, music scores6, and documents.

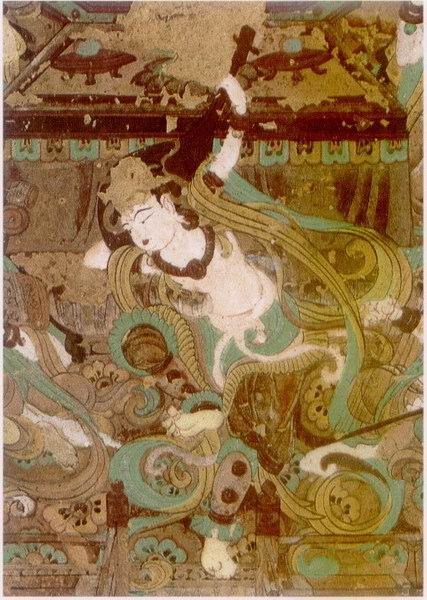

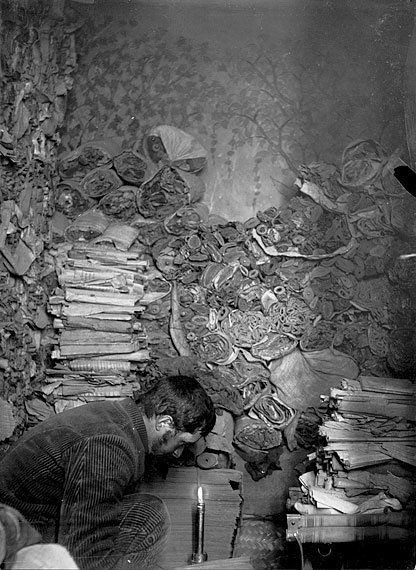

Dunhuang has more than 200 grottoes representing music, depicting many musical ensembles (see Picture 4), musicians (see Picture 5), and musical instruments on their murals. There are images of more than 500 different types of ensembles and more than 40 kinds of musical instruments played in various ways, including blowing, beating, stroking, and strumming, totalling more than 4 500 forms. The Cangjing Cave7 (see Picture 6) also contains scores and other musical materials. These precious documents demonstrate the development of Chinese music over the period of approximately one thousand years. They provide rich material, not only for the study of the history of Chinese music, but also concerning the exchanges between Chinese and Western music. These multi-cultural features have made the Mogae Grottoes a model for the exchange and integration of different ethnic groups, different languages and cultures, and contrasting religious beliefs during their long history. The Mogae Grottoes can thus be considered the Tower of Babel8 of Eastern and Western culture (see Picture 3).

I often wonder how this real and existing Tower of Babel was built, how it survived wars and transcended races and religions, to allow people, from different ethnicities, speaking various languages, and holding different beliefs, to coexist and cooperate to create such a treasure house of art and human culture. In my opinion, the power of faith is the one thing held in common among these different beliefs. That is to say, they share a belief in love and kindness, and the belief that the value of human beings should be to bring goodness into the world.

Dunhuang’s ancient music scores translated by the Oriental Symphony Orchestra

Aside of Dunhuang, Chinese elements are commonly used in Western music and vice versa in modern times. For example, Tchaikovsky9 included a “Chinese Dance”10 in The Nutcracker, and Mahler11 used the poetry of the Chinese poet Wang Wei12 from the Tang Dynasty, and those of other Chinese poets, as the lyrics of Das Lied von der Erde13 (Song Of The Earth). Both Puccini14, in Turandot15, and Debussy16, in Pagoda17, explored Chinese themes. In China, the well-known violin concerto The Butterfly Lovers18, co-composed by He Zhanhao19 and Chen Gang20, is an example of “learning from the West.”

While there are differences between Eastern and Western culture, the practices of our predecessors teach us that those differences can be overcome by goodness, kindness, and the infinite creativity originating in our hearts, with miracles possible. In the post-pandemic era, the development of mankind is faced with numerous hurdles. I wish to follow the footsteps of our precursors, to create music projects in the spirit of communication and tolerance like those represented in Dunhuang, and to build communication bridges over time and geography.

After a conversation with Lu Hang, an expatriate artist in France, we began a cooperation on the Dunhuang music project. In 2019, we were fortunate to work with Mr. Cui Bingyuan21, a famous Chinese composer, also interested in Dunhuang, who had participated in the Dunhuang Ancient Notation Symposium by visiting Dunhuang twice in the same year to collect music. The result will be presented with the support of the National Art Foundation of China. The Oriental Symphony Orchestra (see Picture 8) will use two translated movements derived from the ancient music scores of Dunhuang (see Picture 7) and will also perform five narrative movements that combine Western symphonic music with ancient Chinese musical instruments. Modern projection technology, 3D mapping, and computer design will be employed to allow the audience to imagine the past and the present, and to “feel” the integration of East and West, ancient and modern, from an audiovisual perspective, which aims to reflect the values of tolerance conveyed by Dunhuang for human civilization.

The piece will be performed as follows:

The First Movement—Preface: The East

The composer uses glockenspiel, vibraphone, harp, percussion, and strings to create an ethereal sound, followed by a theme of five consecutive descending strings. The phrase starts the “narrative” of the entire piece, after development and variation.

The Second Movement—Mogao Grottoes stand here: Le Zun

This movement is a dual-theme variation for cello and band. The anthropomorphic cello shows the rich, tenacious inner world of Le Zun from a first-person perspective. Through texture, speed, strength, as well as theme variations, the presented narratives imply the important and long influence Dunhuang has had in the world.

The Third Movement—Translation of Dunhuang music scores One

The third and sixth movements directly show the research findings of Professor Chen Yingshi 22. The third movement consists of the first air “Pin Nong,” the third “Qing Bei Yue,” the fourth “Man Quzi,” the sixth “Ji Quzi,” the 7th “You Quzi,” and the 8th air “You Man Quzi,” from the ten pieces of Dunhuang’s scores (see Picture 9), with B d g a as the tuning of the pipa. Each theme is played according to the pitch of the translated music scores, with part of the scoring moved octaves higher. At the same time, woodwinds and strings are very cautiously involved, under the premise of ensuring the complete expression of the translated notation, to display the multi-voice texture of this section.

The Fourth Movement—Colored Sculptures of Bodhisattvas

The coloured sculptures of Bodhisattvas in Dunhuang are perfect models of human beings. Religious rituals, contemplation, introspection, and joy are represented. This movement is elaborated with adagios and narrated in the form of “questions and answers,” poetically showing the compassionate, pure, and beautiful image of the Bodhisattva. The dignity of divinity and the compassion of the world are transformed into kindness in the sculptural works.

The Fifth Movement—Performing Flying Apsaras

This movement consists of two parts. In the first part, from the beginning to the 71st bar, the theme is composed of an up-and-down melody in B minor, ascending to the sixth level like the colorful streamers of flying Apsaras (Goddess of the wind) swaying in the wind. The second part, starting from the 72th bar, uses bamboo flute and pipa to create dance themes from nature, creating a lively and lightly-bouncing picture. After many variations, the movement ends with a continuous “bounce” by the bamboo flute.

The Sixth Movement—Translation of Dunhuang music scores Two

This movement is also divided into two parts. In the first, the pipa is tuned A c e a, with the 12th air “Qing Bei Yue,” the 13th “You Man Quzi Xijiangyue,” the 16th “You Man Quzi Yizhou,” the 18th “Shui Guzi,” and the 20th air “Changsha Nv Yin” are selected from Dunhuang’s scores. In the second part, the pipa is tuned A c# e a, palying the 22nd air “Sa Jin Sha” and the 24th air “Yi zhou”. In addition to the pipa, this movement also has Chinese bamboo flute, zheng, and multiple percussion instruments.

The Seventh Movement—Dunhuang: Prosperity and Light

The introduction uses the material from the first movement, played five consecutive times to echo the beginning. The first theme is a beautiful soprano solo which represents the magnificent Apsaras, flying and swaying. After the string music is repeated twice, the pipa plays a narrative second theme. The development uses the 12th air, “Qing Bei Yue,” from Dunhuang’s Music Scores, which makes the orchestra sound like an enlarged pipa recital, sonorous and powerful. The “Great Compassion Mantra,” played by the flute, appears at the end, which is not only an echo of the previous movement, but also a vision for a better future.

My heart has long yearned for there, though I can’t go

In 1990, when the Voyager 1 (see Picture 10) 23 spacecraft was about to fly out into the solar system, it took a photograph of the earth from a distance of 6 billion kilometres (see Picture 11). Six years later, Carl Sagan 24, the well-known astrophysicist and science writer, declared 25: “Every one of us lives here—on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.” To the universe, the earth seems so insignificant. To the earth, human beings seem so small.

When confronted with conflicts and collisions between different cultures, we bear greed, hatred and ignorance in us, and unleash wars, disputes, contradictions, and accusations from Pandora’s box26. If we can build relationships of tolerance, understanding, mutual cooperation, and communication through engagement and contemplation, like the humans who once lived in Dunhuang, perhaps we could use more of our time and resources needed to explore truth and redeem our history. This is the direction that each of us should strive for.

Albert Camus once said, “If God exists, all depends on him and we can do nothing against his will. If he does not exist, everything depends on us.” We are mortals after all, and these beautiful visions may be too romantic. Nevertheless, it is precisely because we firmly believe and practice our beliefs, that human society moves forward. More than 2000 years ago, Sima Qian28 said, “My heart has long yearned for there, though I can’t go.”29 What about us today?

References

1 Sogdian (Ancient Persian: Suguda- or Sogdiana), an ancient ethnic group in Central Asia who originally lived in the Sogdiana region of the Zeravshan River between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, Today, it belongs to Uzbekistan, and parts of it are in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdian is made up of oasis countries of different sizes. They were good at doing business, and controlled the trade on the Silk Road.

2 Jianyuan (365-July 385) is the third and final reign title of Fu Jian, Emperor Xuanzhao of the Qin regime during the Sixteen Kingdoms period.

3 Li Kerang’s “Reconstruction of the Buddha’s Niche Stele of Mogao Grottoes” records that the ascetic monk Le zun came to the foot of Sanwei Mountain in the second year of Jianyuan of the former Qin Dynasty (year 366) and saw the “glory” and “Thousand Buddhas”. He dug out the first grotto in history at the Dangquan River Valley at the foot of the Sanwei mountain in Dunhuang, thus creating the splendid Buddhist culture of Dunhuang.

4 Gansu is a province of the People’s Republic of China. It is located in the northwestern region of China and the upper reaches of the Yellow River. Its capital is Lanzhou City.

5 The Mogao Grottoes are located on the cliff at the eastern foot of Mingsha Mountain in Mogao Town, 25 kilometers southeast of Dunhuang City, Gansu Province. The caves are staggered, row upon row, with up to five floors above and below. They were begun in the pre-Qin period of the Sixteen Kingdoms, and their construction continued through the Sixteen Kingdoms, Northern Dynasties, Sui, Tang, Five Dynasties, Xixia, Yuan, and other dynasties. There are 735 caves, 45,000 square meters of murals, and 2415 clay sculptures. It is the largest and richest surviving Buddhist art site in the world. The Library Cave, discovered in modern times, contains more than 50,000 ancient cultural relics. In December 1987, Mogao Grottoes was listed as a world cultural heritage site.

Fokan Ji 《佛龕記》 Original text: 莫高窟者厥,秦建元二年,有沙门乐僔,戒行清忠,执心恬静。当杖锡林野,行至此山,忽见金光,状有千佛。□□□□□,造窟一龛。

6 “Dunhuang Musical Scores,” also known as “Dunhuang Music Scores” or “Dunhuang Pipa Score,” is a set of pipa scores found in the Library Cave. On May 26, 1900 (26th year of Guangxu, Qing Dynasty), Taoist Wang Yuanlu found a closed stone chamber in Mogao Grottoes, and among more than 40,000 volumes of Buddhist scriptures, poems, and letters, found the “Dunhuang Music Scores” and “Pipa Twenty Scores Table.”

Ponampon, Phra Kiattisak (2019). Dunhuang Manuscript S.2585: a Textual and Interdisciplinary Study on Early Medieval Chinese Buddhist Meditative Techniques and Visionary Experiences. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. p. 14. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

7 In 1900, a Taoist priest called Wang Yuanlu who lived in Mogao Grottoes carried out a large-scale cleaning in order to convert part of the caves that had been abandoned into Taoist temples. When he was clearing the silt in Cave 16 (numbered later), he stumbled upon a small door on the wall of the corridor on the north side. When it was opened, a square room with a length of 2.6 meters and a height of 3 meters appeared (now numbered Cave 17), containing more than 50,000 documents and cultural relics such as paper paintings, silk paintings, and embroidery from the 4th century to the 11th century (that is, from the Sixteenth Kingdom to the Northern Song Dynasty), which was later named “Cangjing Cave.”

8 The “Tanah Genesis” (also called “Hebrew Bible” or “Old Testament” “), tells the story of the origin of the different languages produced by human beings. In this story, a group of people who spoke a single language came to the Shinar (Hebrew: שנער) area, migrating from the east after the “Great Flood.” They decided to build a city and a tower, the Tower of Babel (Hebrew: מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל, Migdal Bāḇēl), tall enough to reach the heavens. God, observing this, confounded their speech so that they could no longer understand each other, and scattered them throughout the world.

9 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian name Пётр Ильич Чайковский) May 7, 1840-November 6, 1893, a Russian composer of the Romantic period.

10 “Chinese Dance” In the second act of The Nutcracker. In it, Tchaikovsky built a lively and gorgeous candy kingdom through a piece of dance music.

11 Gustav Mahler (July 7, 1860-May 18, 1911), Austrian composer and conductor.

12 Wang Wei (692-761), Tang Dynasty, landscape painter and pastoral poet.

13 Das Lied von der Erde is a large-scale vocal symphony by the Austrian composer Gustav Mahler. Mahler stated that his work was taken from Hans Bethge’s “Chinese Flute.” There are six movements in the work, using seven Tang poems from the poet Hans Bethge’s free translation collection, “Chinese Flute” (Die Chinesische Floete, published in 1907) as the lyrics.

14 Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini (December 22, 1858-November 29, 1924), Italian composer whose famous works include operas such as La Boheme, Tosca, and Madame Butterfly, which are frequently performed today.

15 Turandot: “Turandot” (Italian: Turandot) is a three-act opera composed by Giacomo Puccini. The script is adapted from the creation of Italian playwright Carlo Gozi. After Puccini’s death, Franco Alfano completed the play based on Puccini’s draft. In the opera, Puccini partly adopted the tune of the Chinese folk song “Jasmine”.

16 Debussy:Achille-Claude Debussy (French: Achille-Claude Debussy; August 22, 1862-March 25, 1918), French composer. Debussy was one of the most influential composers at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

17 Pagoda is the first piece of the French composer Debussy’s piano work Estampes, composed in 1903.

18 Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai Violin Concerto (“The Butterfly Lovers”), often abbreviated as “Liang Zhu Violin Concerto” or “Liang Zhu,” was created by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, students from the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, based on the Yue opera Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai..

19 He Zhaohao (August 29, 1933 – ) Chinese musician, Zhuji, Zhejiang native.

20 Chen Gang (March 10, 1935 – ), Han nationality, Shanghainese, Chinese pianist and composer.

21 Cui Bingyuan, born April 1956 in Fengcheng, Liaoning. Chinese national-level composer, member of the Chinese Musicians Association, director of Shaanxi Musicians Association, full-time composer of Shaanxi Song and Dance Theater, deputy dean of Xi’an Conservatory of Music.

22 Chen Yingshi (1933-2020), professor at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, mentor for Doctoral candidates and consultant for the Chinese Music History Society and the Chinese Musical Temperament Society.

23 Voyager 1 is an unpiloted outer solar space probe developed by NASA, launched on September 5, 1977. It is the first man-made spacecraft to have left the solar system, and the farthest man-made spacecraft from the earth in history. On August 25, 2012, it became the first spacecraft to cross the solar system and enter the interstellar space.

24 Carl Edward Sagan (November 9,1934-December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, astrophysicist, cosmologist, science fiction writer, and founder of the Planetary Society.

25 “From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it’s different. Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.”

“On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

“The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar,’ every ‘supreme leader,’ every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

“The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner.

“How frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.”

Sagan, C., Pale Blue Dot: a vision of the human future in space, Random House, 1994.

26 The Buddhist concept of Greed refers to the greed for the five desires, hatred is anger, intolerance, and ignorance is foolishness and delusion. Because greed, hatred, and ignorance can poison people’s lives and wisdom, they are called the “three poisons.” The reason for their being called “poisons” is that, like poisons, they can harm all living beings, and are the root of all the troubles in the world.

27 “Si Dieu existe, tout dépend de lui et nous ne pouvons rien contre sa volonté. S’il n’existe pas, tout dépend de nous,” Le Mythe de Sisyphe, éd. Gallimard, 1994, p. 16

28 Sima Qian (145 BC-early 1st century BC), courtesy name Zichang, was born in Longmen (Hancheng—Shaanxi nowadays), a historian and writer of the Western Han Dynasty. The “shiji” (Records of the Grand Historian) written by Sima Qian are recognized as a model of Chinese history books.

29 Originally from “The Book of Songs—Xiaoya·Chexia.” Later, Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian: Confucius Family” specially quoted it to praise Confucius. “The Book of Songs has it: ‘his character is like a mountain for people to look up to, and people can’t help but follow his behavior as the code of conduct. My heart has long yearned for there, though I can’t go (there).’ This changed the original meaning.

Wang Muxi was born in Beijing in 1988. Studied violin since childhood. Studied in the middle school attached to the Central Academy of Arts and crafts in high school. Graduated from Beijing Dance Academy in 2010, Stage Design.

Since 2018, she has served as the executive director of China Oriental Symphony Orchestra, designed and produced the symphonic music project “Dunhuang’s Ancient Music Scores Translated by Oriental Symphony Orchestra” , which has won the support of China National Art Foundation. And is committed to promoting the popularization of aesthetic education in China.

Hang LU is an artist, graduate of the Fine Arts Institute of Sichuan in China and the School of Fine Arts of Bourges in France. He has exhibited at the Blue Roof Museum in China and Galerie Crous in France.

Wang Muxi was born in Beijing in 1988. Studied violin since childhood. Studied in the middle school attached to the Central Academy of Arts and crafts in high school. Graduated from Beijing Dance Academy in 2010, Stage Design.

Since 2018, she has served as the executive director of China Oriental Symphony Orchestra, designed and produced the symphonic music project “Dunhuang’s Ancient Music Scores Translated by Oriental Symphony Orchestra” , which has won the support of China National Art Foundation. And is committed to promoting the popularization of aesthetic education in China.

Hang LU is an artist, graduate of the Fine Arts Institute of Sichuan in China and the School of Fine Arts of Bourges in France. He has exhibited at the Blue Roof Museum in China and Galerie Crous in France.