The lives of each and every one of us is defined by the anxiety/hope tandem. In the words of La Rochefoucauld, “Hope and fear are inseparable, there is no fear without hope, nor hope without fear.” (Ripert, 2002). We are all, as Leonardo da Vinci described, standing before a dark cave, our hearts torn between the fear of potential threats lurking in the dark (as seen in the detail of Saint Jerome in the Wilderness) and the desire to know whether there may in fact be something “miraculous” to be found (as seen in the detail of the Virgin of the Rocks) (E-Leo):

E tirato dalla mia bramosa voglia, vago di vedere la gran copia delle varie e strane forme fatte dalla artifiziosa natura, ragiratomi alquanto infra gli onbrosi scogli, pervenni all’entrata d’una gran caverna, dinanzi alla quale restato alquanto stupefatto, e igniorante di tal cosa, piegato le mie reni in arco, e ferma la stanca mano sopra il ginocchio, e colla destra mi feci tenebre alle abbassate e chiuse ciglia, e spesso piegandomi in qua e in là per vedere se dentro vi disciernessi alcuna cosa, e questo vietatomi per la grande oscurità che là entro era. E stato alquanto, subito salse in me due cose: paura e desiderio, paura per la minacciante e scura spilonca, desidero per vedere se là entro fusse alcuna miracolosa cosa. (Codex Arundel 155r)

Pandemic And Climate Crisis

Our present historical period is defined by the fact that the anxiety/hope tandem is present in the lives of the collective group. Regardless of where we live, we all simultaneously share the same anxiety and the same hope.

The pandemic has managed to achieve what the climate crisis seems to have failed to bring about, mainly because of a lack of awareness regarding the true extent of the climate crisis. It is worth noting that the health crisis and the climate crisis share many similarities:

– Both represent challenges on a global scale.

– Both are amplifying devices for poverty, social exclusion, and inequality.

– Both require the guidance of science. On this matter, the health crisis has given us a lesson in terms of the appropriate method to adopt, which is granting attention and credit to scientific data and advice.

– Both require a long-term response on every level.

What differentiates the two crises for the time being is the violence with which the pandemic has altered our lives in comparison to the climate crisis, which is in fact the reason why the response to the latter has been so much weaker and slower. It goes without saying that the climate crisis cannot be solved within the same time frame that is being projected for overcoming the pandemic, but current events have shown that widespread change is possible provided the risk is properly understood on a global scale.

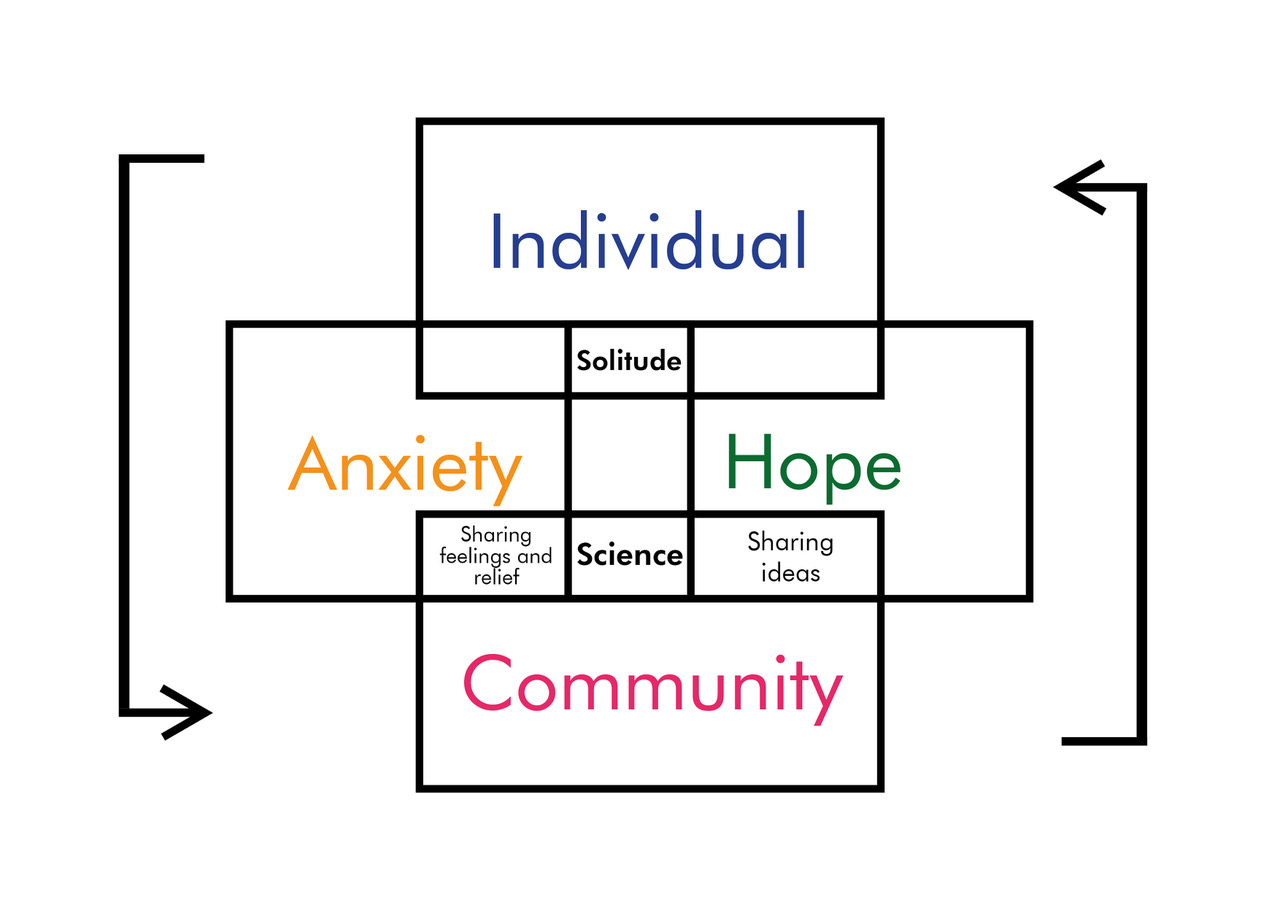

Knowing that we share these two states of mind—anxiety and hope—helps soothe the sense of loneliness that usually goes with the individual experience of this duality. We should not be surprised to discover that we share common symptoms of anxiety and fear concerning the virus and its consequences. Hope, on the other hand, takes on different shapes depending upon each person’s specific situation, even if we do all wish for the same thing—a future in which we can clearly see our place and role in the world.

Renaissance

Each and every one of us hopes for “renaissance.” Our desire for it, or to again quote Leonardo, our “fear of emptiness”—”Il voto nasce quando la speranza more” (MsH 48v, E-Leo) (“Emptiness arises where hope perishes”)—comes with a concern for the future which, although natural and even positive under normal life circumstances—”Paura ovvero timore è prolungamento di vita” (MsH 32r, E-Leo) (“Fear is necessary to push us to live, to ‘prolong our life’.”)—is currently at risk of bringing us to a dead end, crippling our sense of initiative.

In order to avoid this risk, and instead to set out with new ambition and a fresh mindset, we must show great resilience, and share our individual thoughts with the aim of transforming them into collective action. Delacroix said, “Hardship restores to men the virtues taken from them by good fortune” (Ripert, 2002). Since the pandemic, we are all more creative, committed to finding innovative solutions on an individual basis, all the while reflecting on a group, regional, and global scale. Creativity and science go naturally hand in hand, together combining rigorous methods and innovative approaches (Figure 1).

The current health crisis has sent out a clear signal: the world needs science. It has even become evident to those who once only credited science for its technological applications. As a result, it is no longer just scientists but everyone who demands research to be funded, doctors to be protected, and young scientists to be recruited. What selfishness this pandemic has revealed! This newfound “awareness” now stands where there was once the indifference that scientists have been a witness to at every cut to funding, and every outcry condemning the precarious working conditions of our researchers, all the while knowing that for many, either sick or related to the sick, life is a constant state of emergency, a constant worry about an all-too-near death, a painful wait for a drug still under trial due to a lack of research funds, a heart-wrenching desire for normality that is never satisfied.

The current pandemic has taught us valuable lessons about the relationship between science and society. Given their ethical, moral, and social implications, they should both become integral components of modern-day general education—not just scientific education.

Lessons On Science For Society

Science As A Beacon For All

Our history will be divided into before and after coronavirus, but science is and will always be about culture and progress, and today it offers us a life lesson; in these times filled with uncertainty and doubt, science has guided us by providing fact-based information. Let us summon, to this effect, Leonardo’s beautiful definition of science:

E veramente accade che sempre dove manca la ragione suppliscono le grida, la qual cosa non accade nelle cose certe. Per questo diremo che dove si grida non è vera scienza, perché la verità ha un sol termine, il quale essendo pubblicato, il litigio resta in eterno distrutto, e s’esso litigio resurge, ella è bugiarda e confusa scienza, e non certezza rinata. Ma le vere scienze son quelle che la speranza ha fatto penetrare per i sensi, e posto silenzio alla lingua de’ litiganti, e che non pasce di sogni i suoi investigatori, ma sempre sopra i primi veri e noti principi procede successivamente e con vere seguenze insino al fine, come si dinota nelle prime matematiche, cioè numero e misura, dette aritmetica e geometria, che trattano con somma verità della quantità discontinua e continua. (Libro di pittura 19r-19v, E-Leo)

According to Leonardo, “where reason is not, its place is taken by clamour,” and “where there are quarrels, there true science is not.” True science is that which hope has passed through the senses, which does not feed illusions to its students, and which moves forward according to principles, in a sequential manner, until it reaches its goal. He gives the example of arithmetic and geometry, which “truthfully” study continuous and discontinuous quantities. Leonardo thus proves himself a true “modern scientist,” given that today the awareness is that scientific disputes are resolved by allowing unfettered competition among different explanatory models, which are then compared on the basis of observation, experimentation, and calculation, following a criterion of coherence between the models and reality.

A great lesson that science gives us in this complex and complicated situation is the role that each of us must play. Science now teaches us, more efficiently than ever, that it is not a matter of choice, that the correct phrase is “each of us must do their part,” if not through knowledge and skill, then at the very least through a sense of civic responsibility that makes us see ourselves as being part of a community—in our case, the world—whose proper functioning, balance, and well-being depend upon the level of our commitment and our involvement in becoming ambassadors for the values of science. In this way, science develops our sense of individual, collective, and shared responsibility.

Science also guides us by teaching us teamwork based on dialogue and humility. In the world of science, the golden rule is that strength is measured by talent and skill. Here, humility is not a sign of weakness but a sign of strength. In these trying times, everyone remains humble in front of experts, recognizing the value of their expertise.

The Fundamental Role of Expertise and Skill

Today, everyone humbly acknowledges the value of scientific expertise. Scientists are acknowledged because each of us, throughout the world—decision makers included—needs to feel reassured and supported, and in good hands. And the good hands are those of scientists working day and night in order to save lives and find urgent solutions to the multiple and serious consequences of the current pandemic.

The need for excellence in science is no longer just a slogan. It is also the best response to fake news. Everyone can now understand the frustration scientists experience in fighting against the dangerous information that claims to be scientific fact despite the absence of the scientific community’s validation. We must however admit that scientists are not yet sufficiently committed, as the committees for ethics and integrity in research recommend, to the one hand correcting the scientific content that is fraudulently published, and on the other hand intervening, on social networks or other popular media, to bring the debate back to a level of objectivity and transparency and to restore the credibility of science.

Success of the Interdisciplinary Approach

Due to the need to encompass a wide range of fields during the current sanitary crisis, successfully-activated international interdisciplinary scientific collaborations have underlined the ability of science to overcome geographic and disciplinary borders—and often barriers.

In these difficult times, everyone is witnessing the success of the interdisciplinary approach that has proven crucial in addressing global challenges like the health and climate crises. Despite official statements, the interdisciplinary approach has yet to be properly valued and acknowledged. A desirable outcome for this late-blooming awareness could be that the interdisciplinary approach finally finds its rightful place through a thorough evaluation of interdisciplinary scientists and research.

Lessons On Society For Science

Success Of The Transdisciplinary Approach

The scientific community is increasingly aware of the need to expand its efforts to improve the communication of scientific knowledge, and thus contribute to shaping critical thought. Scientists have been recognized for their expertise, and as such have a moral duty to effectively interact with society in an effort which is not only interdisciplinary but transdisciplinary, meaning that it involves society.

The only way to bridge the wide gap that still exists between science and society is to promote and intensify dialogue and interaction. The urgent and crucial awareness of scientists must be accompanied by a concrete commitment on the part of private and public institutions to funding for training scientists in science communication, and by a structured commitment on behalf of scientists to add to their many tasks a constant interaction with society in order to popularize research results and to promote and defend the values and ethical principles of science.

Relations with Decision Makers

Scientists have been recognized worldwide for their expertise, but in order to establish this recognition permanently, it is necessary that their interactions with decision makers be built on solid foundations and based on trust. Scientists, having received the much-coveted attention of decision makers in times of crisis, face the complicated task of improving this complex relationship, in which both parties play a fundamental role—with, on one hand, decision makers consistently requesting help and advice, and on the other, scientists providing a steady flow of appropriate information.

In this context, training scientists in communication is crucial, and must include moral and social aspects in order to transmit the values of science, which are also the values of democracy and coexistence.

Contrary to the climate crisis, for which scientists have long been calling for a change of rhythm and paradigm to little avail, the pandemic has taught decision makers to listen to scientists and make—or at least try to make—decisions based on science. To achieve a sustainable future, and to keep the work of scientists from being dismissed by indifference—or worse, by private interests— while the change of rhythm has been violently imposed by pandemic, it is up to policy makers to lead the way toward a decisive paradigm change based upon the new social consciousness and upon the laws of scale that science has brought forth—i.e., the protection, care, respect, and solidarity which operate within our families must be implemented on a global scale.

A Lesson On Women Scientists For Science And Society

Sadly, we seem to have missed yet another chance to give a voice to female scientists. While women have undeniably played a key role in the most violent phase of the pandemic, they have been almost completely ignored in the current reconstruction phase, and have yet to be given the space to contribute in this global challenge that requires everyone’s help.

In Italy, a group of women issued a letter to the Prime Minister demanding that he appoint a larger number of women to the scientific and technical committee aiding the government, the “Task force per la ricostruzione” (“Reconstruction task force”), in which women are still the minority.

What is even sadder is that domestic work, drastically heightened by the pandemic, is still almost exclusively attributed to women, making their condition incompatible with a professional career—in the field of science or any other. But as the UNESCO-L’Oreal International Programme For Women in Science has long stated, “The world needs science and science needs women.” So, if science is indeed a beacon of light, it is crucial that women scientists be given the chance to share with men the role of lighthouse keepers.

We must keep this in mind when considering the education of our children. We must convey the message that the fight against gender-based discrimination is part of the larger fight for human rights, and is essential in helping to strengthen the position of women as driving forces of change, as outlined in the 2030 Programme of the United Nations. Teaching the practice of respect is an essential part of the urgently-needed mentality shift whose distinctive feature must be interdisciplinarity. It is vital that we adopt a holistic approach, based on equal rights, social justice, respect for cultural diversity, international solidarity, and shared responsibility.

The great merit of the pandemic in relation to science, and above all to the science/society relationship, is that it has highlighted the extraordinary power of science in effectively changing mentalities. In the words of Niels Bohr, “Each great challenge carries within it its own solution. It forces us to alter our way of thinking in order to find it” (Ripert, 2002). The pandemic has demonstrated what scientists have long known, that it is possible to have a scientific approach to life without being a scientist, and that in this way, life actually becomes much easier.

The most noble example of science’s ability to facilitate and improve our lives is best illustrated by modern science’s contribution to the shaping of the democratic ideal (College de France, 2014 and Corbellini, 2011), according to which decisions are made based upon information acquired through extensive analysis of facts. By encouraging people to think for themselves, to accept the existence of different points of view, and to evaluate different opinions using plausible and—as far as possible—objective criteria, scientific education has contributed and continues to contribute to the spread of the spirit of democracy.

Federic Migliardo is Professor in experimental physics at the University of Messina, Italy. She is currently serving as president of the scientific council of the Conference of the Parties in the Centre-Val de Loire region and is a member of the National Commission on Research Ethics and Integrity and the EURAXESS committees. Her research has been awarded through the international UNESCO-L’Oréal For Women in Sciences Programme. She also works with the National Geographic Sciences Festival in Rome and is co-founder of the project Sciences for Life for Lampedusa.

Federic Migliardo is Professor in experimental physics at the University of Messina, Italy. She is currently serving as president of the scientific council of the Conference of the Parties in the Centre-Val de Loire region and is a member of the National Commission on Research Ethics and Integrity and the EURAXESS committees. Her research has been awarded through the international UNESCO-L’Oréal For Women in Sciences Programme. She also works with the National Geographic Sciences Festival in Rome and is co-founder of the project Sciences for Life for Lampedusa.