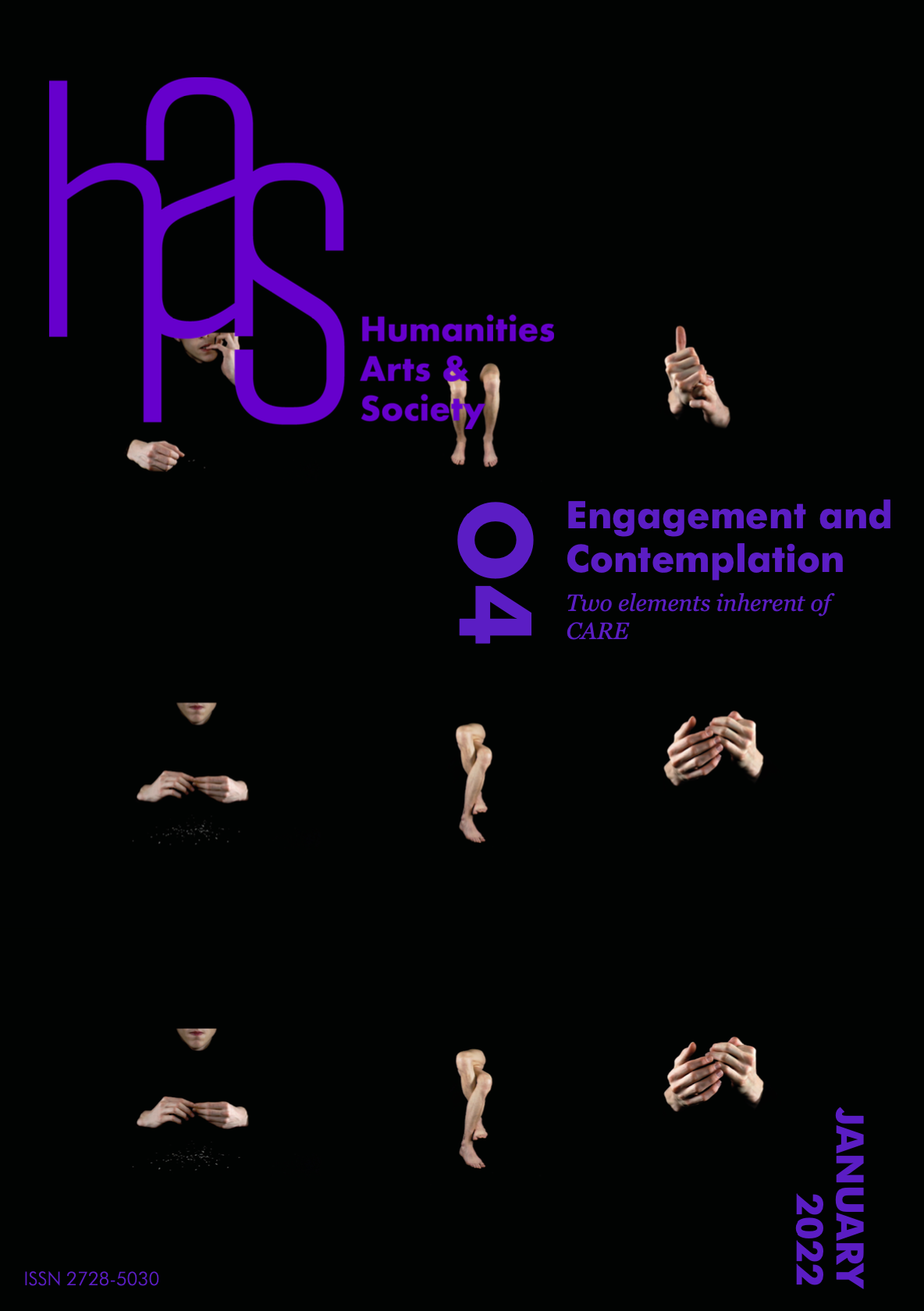

Sarah Nesbitt – Marevna Vorobëv’s Story – Pigmented Inkjet Print on Canvas, Hand-Me-Down Frame, Waxed String, Cut Tacks

2021

We live in a time in which history is being reconstructed, and opinions are misinterpreted as evidence-based facts. For this reason, we should know what constitutes accurate, reliable information.

To evaluate the gap between accuracy and fiction, I research forgeries, stolen artwork, plagiarism, memory, censorship, misattribution, and the writing and rewriting of history. My goal is to create broad awareness of our shortcomings in recording and portraying history so that people understand it, not as a static narrative frozen in the past, but as a medium of active engagement—a living, breathing investigation into what came before, constantly striving to reach the truth. In my recent art project, Stories To Tell, I sought to highlight how certain artists end up being left out of art history to create more time, care, and space for artists who fit the White European Male archetype. By highlighting these artists, I attempt to create a more accurate depiction and a deeper appreciation of art history.

Stories To Tell is a series of printed stories on canvas, of artists who have faced significant adversity, but have figured out ways to move forward. I love talking about this project. It started in my art history classrooms (I teach), where I found that the realm of art history has a terrible habit of leaving out talented artists due to sex, race, culture, and/or class. I found myself having trouble finding art history textbooks that included a wider, more realistic depiction of the artistic community, so I would teach my students about artists who weren’t appreciated as much as the “usual suspects” (white, male, European). I find that sharing (and seeing) these kinds of stories can allow people to feel connected to these artists, even if they existed well before the audience’s time. This project is a way for me to bring these rarely-discussed stories of hardship and encouragement out of the classroom and into the public. Bringing light to marginalized artists throughout history not only revitalizes forgotten artists of the past—and present—from all over the world, but encourages us to seek a more accurate depiction of our own histories.

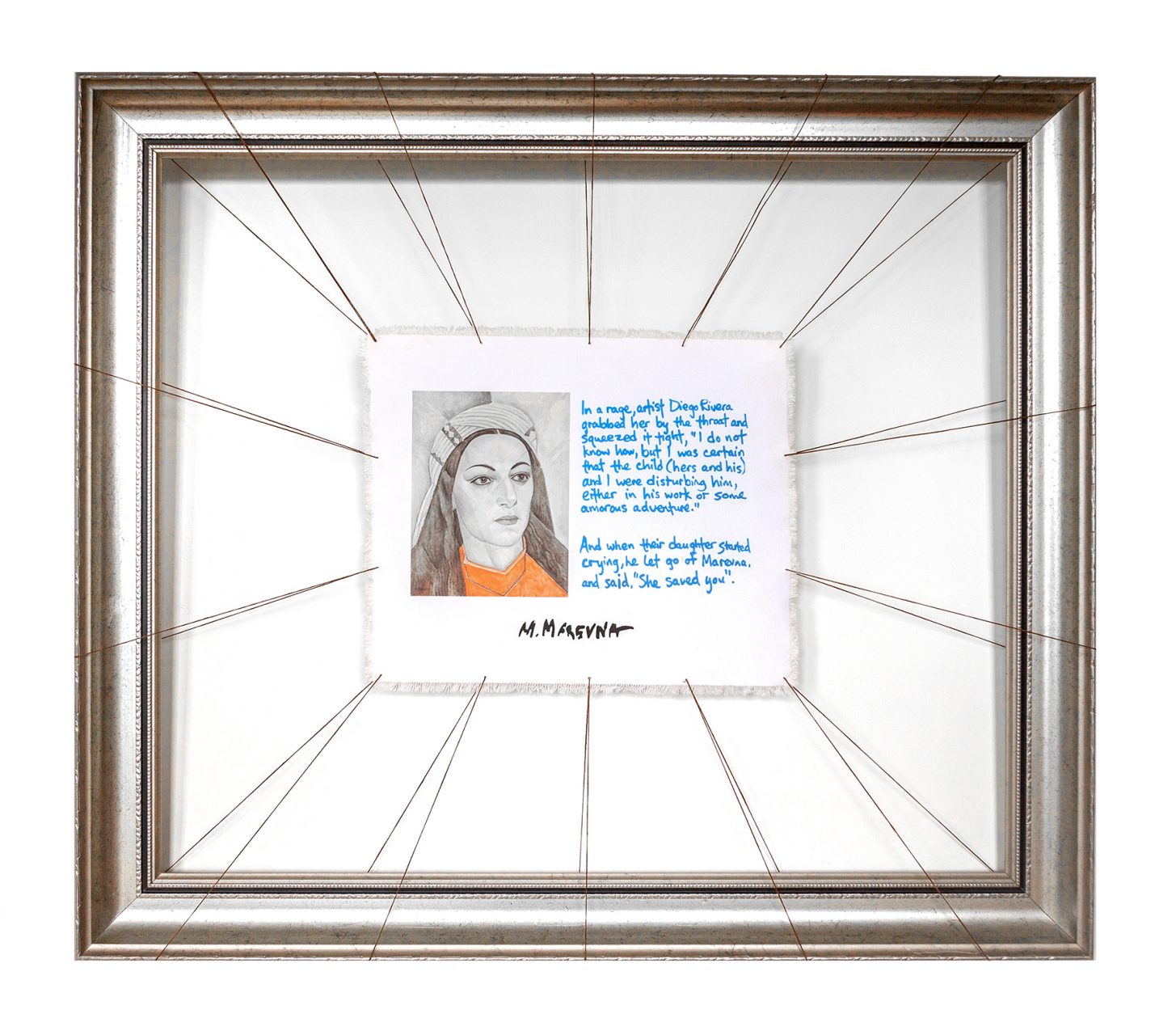

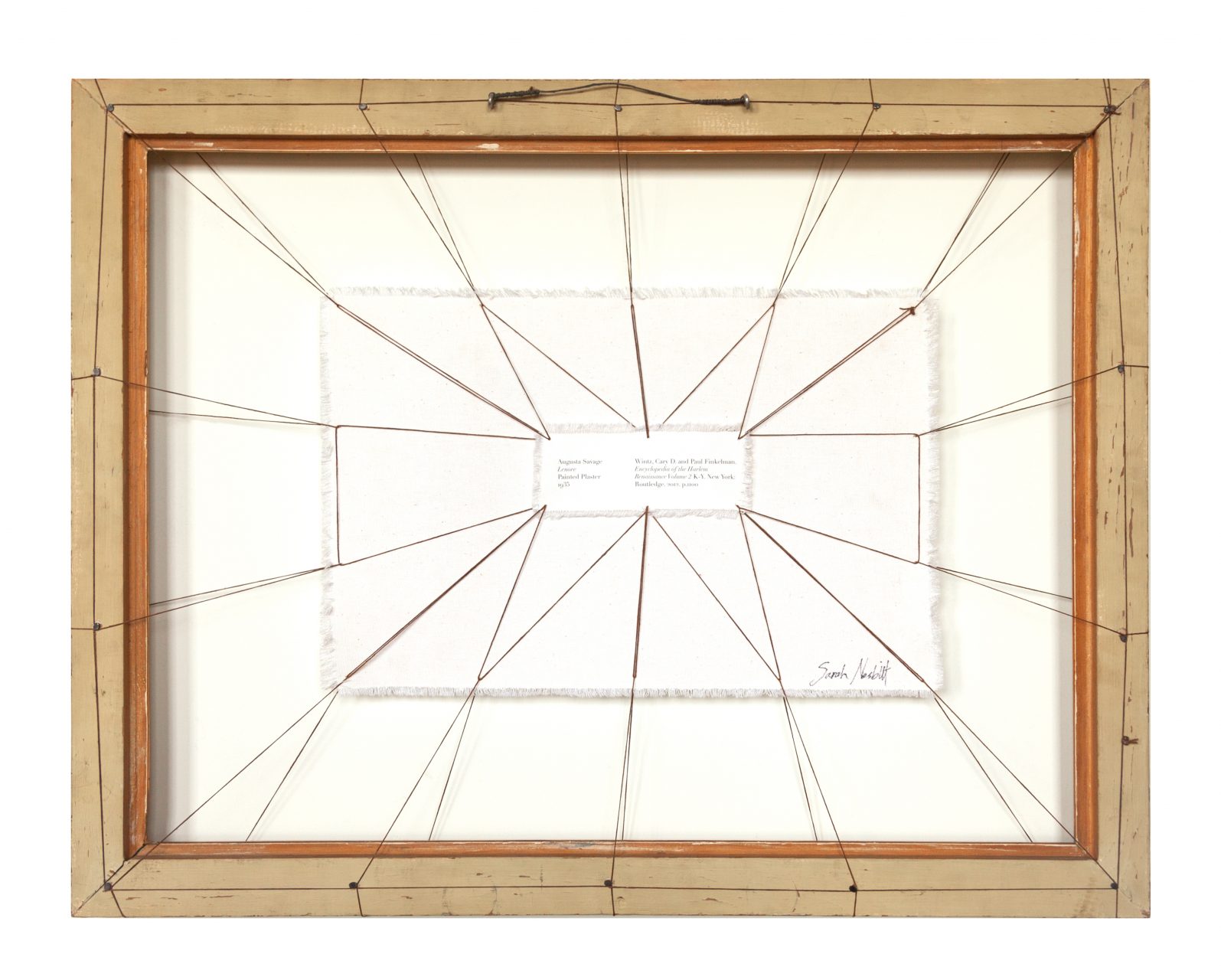

Sarah Nesbitt – Augusta Savage’s Story (1) – Pigmented Inkjet Print on Canvas, Hand-Me-Down Frame, Waxed String, Cut Tacks

2021

The stories vary from hope to frustration. They come from people who tell their own lives, or from people who advocate for others. They are stories of female and LGBTQIA visual artists. Imagine the number of stories from other fields and genders, untold due to feelings of trauma, shame, fear, mourning, and for many other reasons.

The stories are not exaggerated. They are not meant to be seen as an accepting view of the art community—we should do better than that, to relate what these people had to go through. The romanticized view of an artist as a desperate, starving, elitist, tortured, sex-crazed soul is a harmful stereotype. It diminishes the importance of the role that the arts play in our everyday lives, in how we perceive the world, and how we can communicate with each other. It also disrespects the artist. I’ve had many people look down on me if I tell them I am an artist, and I know that part of that has to do with this negative stereotype.

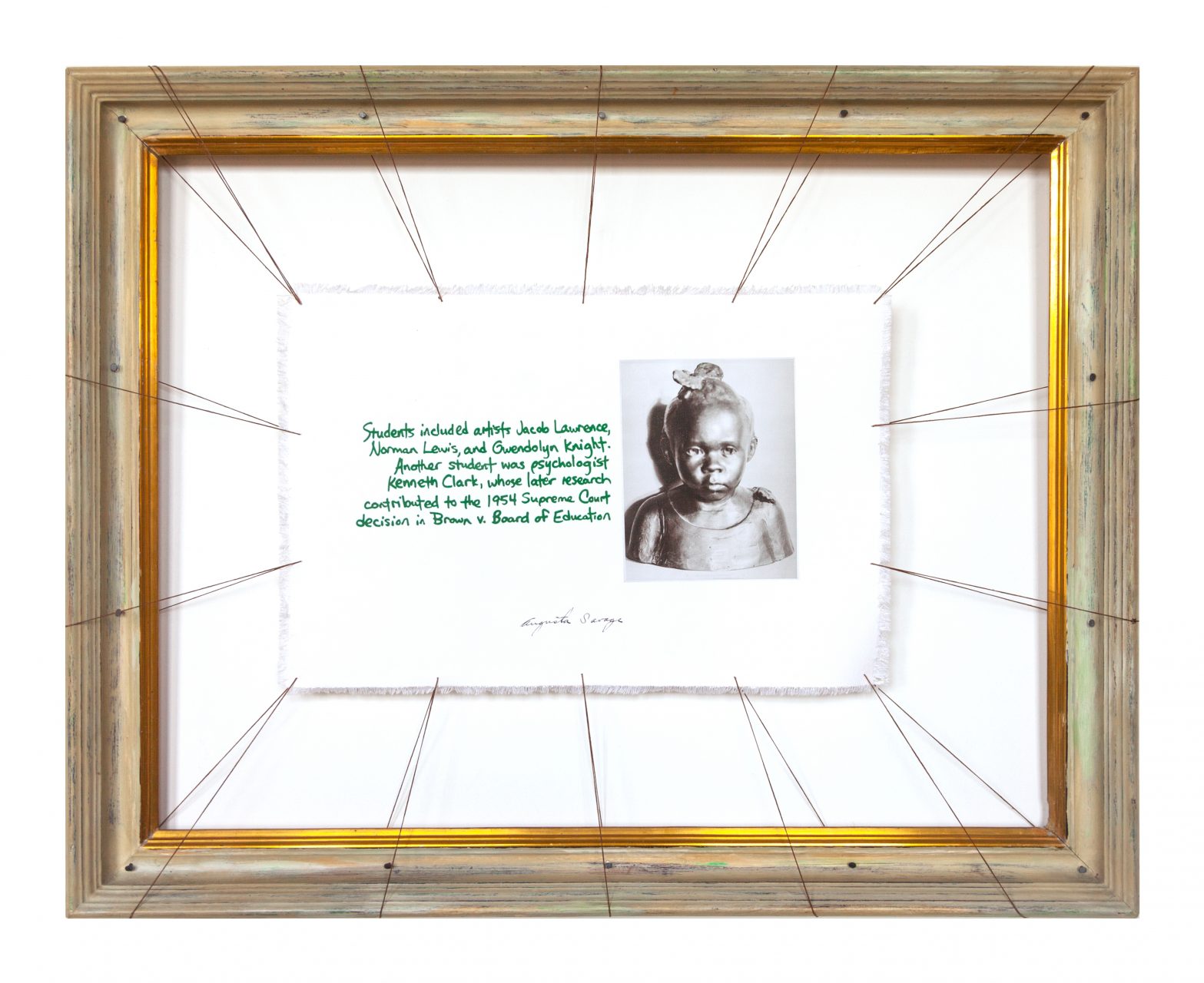

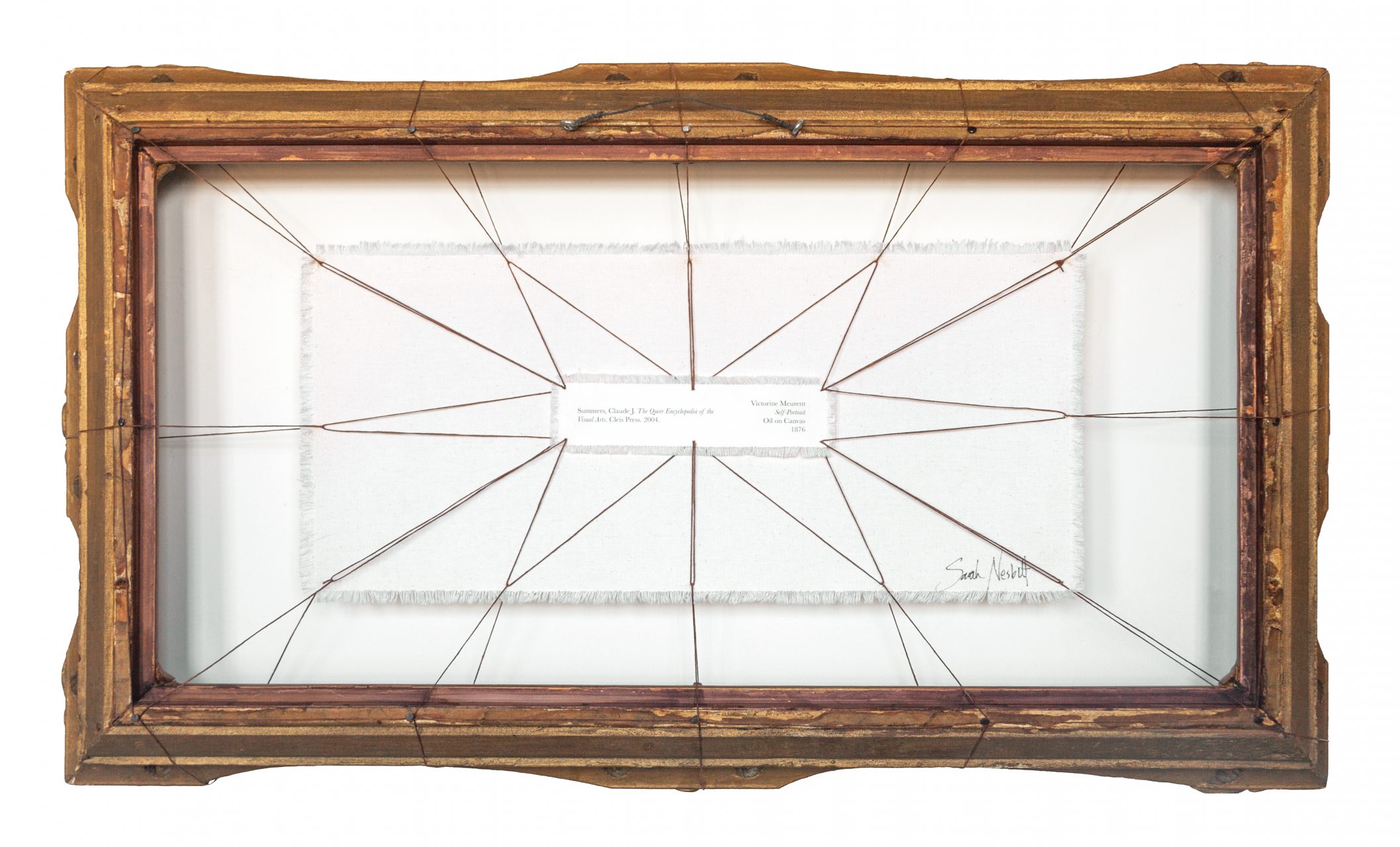

Sarah Nesbitt – Victorine Meurent’s Story – Pigmented Inkjet Print on Canvas, Hand-Me-Down Frame, Waxed String, Cut Tacks

2021

Using waxed bookbinding string and hand-me-down frames, I have attempted to highlight how close these artists have gotten to become well-known artists. The bookbinding string is the same as the string used to assemble the textbooks that teach people who the “great” artists were. The hand-me-down frames symbolize the ways these artists end up being ignored to pay attention to artists who fit the White European Male archetype.

Life in Two Worlds.

London: Abelard-Schuman. 1962. p. 253

Text on the right : Marevna Vorobëv

Portrait of Marika, the Artist’s Daughter (1919-2010)

Oil on Canvas

Year Unknown

Sarah Nesbitt

Lenore

Painted Plaster

1935

Text on the right : Wintz, Cary D. and Paul Finkelman.

Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance Volume 2 K-Y. New York: Routledge. 2012. p.1100

Sarah Nesbitt

The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts.

Cleis Press. 2004.

Text on the right : Victorine Meurent

Self-Portrait

Oil on Canvas

1876

Sarah Nesbitt

I don’t excuse talent or “genius” as an excuse to justify praising those who violate others. I have purposefully left out or harshly judged artists who have prevented others from reaching their full potential. Though I have been influenced by artists who I later found to be in this category of people. I take these discoveries as opportunities to praise others who don’t fall into this category. We shouldn’t praise people who become disillusioned by power, and who exploit others for their race, sex, or sexuality.

Sarah Nesbitt was born in Syracuse, New York, and has an MFA in Photography at Pennsylvania State University and a BFA in Photography and Drawing at the State University of New York at Oswego. Her interests lie in studying how history is used and perceived, in conjunction with investigating the importance of people’s actions and behaviors towards that information acquired by them.

Her work has been featured in publications such as The Washington Post, Hyperallergic, the third edition of The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes(Cengage Learning Press), Photographer’s Forum, Detroit Metro Times, Meanings and Makings of Queer Dance (Oxford University Press), and Theatre Topics (John Hopkins University Press).

Sarah Nesbitt was born in Syracuse, New York, and has an MFA in Photography at Pennsylvania State University and a BFA in Photography and Drawing at the State University of New York at Oswego. Her interests lie in studying how history is used and perceived, in conjunction with investigating the importance of people’s actions and behaviors towards that information acquired by them.

Her work has been featured in publications such as The Washington Post, Hyperallergic, the third edition of The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes(Cengage Learning Press), Photographer’s Forum, Detroit Metro Times, Meanings and Makings of Queer Dance (Oxford University Press), and Theatre Topics (John Hopkins University Press).