© Anaïs Pachabézian

In dialogue with

Petit Inventaire Familiale

by the artist Anaïs Pachabézian

I recently discovered a suitcase of family letters that my mother had stored and was reminded of something long forgotten. Coming to the UK as a child, I had to forget my cursive script and learn how to write again, but in print. I also remembered that it was my love of reading and of the natural world which sustained me during that time. I was not alone in this—Waterstones’s Children’s Laureate Cressida Cowell notes that “Decades of research show a reader for pleasure is more likely to be happier, healthier, do better at school, and to vote-all irrespective of background.”1 Now, working as a visual artist and educator, stories still inspire me. They make visible new possibilities, bring into definition my values and beliefs and help me imagine different futures for myself and others. What I read generates new ideas that I can be curious and care about.

© Anaïs Pachabézian

We could consider contemplation and engagement as thoughts/ideas (internal) and actions (external) respectively, conducted by the mind and body. However, this implies a linear relationship between the two and is limiting, as it excludes emotions and the heart. If we contemplate something, such as a story, we are in effect engaging with it. Whether as myth, news, jokes, or parts of conversations, stories can generate an emotional response. They can help us empathize with a situation, context, or characters, and build a sense of home. As George Saunders notes, “What a story is ‘about’ is to be found in the curiosity it creates in us, which is a form of caring.”2

© Anaïs Pachabézian

© Anaïs Pachabézian

Sharing stories can also be perceived as a way of showing we care, and can contribute to our well-being and sense of identity. We remember fables from our childhood and recount them to our grandchildren. Sometimes, stories are our only memories of people and places we have lost or had to leave. Depending upon the storyteller’s intention, they can be used to include and exclude, unite and divide, inspire and control, be a means to an end and an end in themselves. There is a difference, however, between caring about something or someone and caring enough about something or someone to change how we think and behave. This is where the application, and transfer, of values and skills gained from engaging with and reflecting on stories can play a part. Sarah Mears makes the point that, “Reading gives children the opportunity to practice feelings of empathy that they can transfer to real-life situations.”3

As we read, we are often exposed to diverse ways of living and thinking. While discussing the process of writing stories, Michael Rosen reflects, “What we create are the mixture of ideas and feelings tied together so it’s almost seamless.”4 To hold and hear someone else’s words within ourselves in an immediate and intimate communication is a powerful experience. It can reaffirm, change, challenge, or impact our understanding of ourselves, others, and the world around us.

© Anaïs Pachabézian

© Anaïs Pachabézian

One of the things that makes us unique is how we choose which of our experiences we want to examine or ignore. Hannah Critchlow states, “Our individual sense of reality is a construct and the potential for differences in the reality that shape different individuals’ experience is vast.”5 Our personal narratives influence our actions and thoughts, and therefore our engagement with and contemplation of the world. In many creative mediums, including literature and art, there has been an investigation of the relationship between our inner and outer worlds, between emotions and nature. As I started to be able to identify new trees such as Sycamore and Horse Chestnut as a child, I began to feel a sense of belonging. The idea of a different kind of literacy, that of nature, is identified and explored by Robert Macfarlane.6 Building a relationship with a place, a person, or an animal is a way to begin to understand, and subsequently care. If we can provide opportunities and access for people to connect to places through emotions, stories, and ideas, over time we may be able to create more diverse communities.

We can also consider the relationship between stories and time through the lenses of history and memory, hopes and dreams. The power of words includes their ability to let us feel, anticipate, reflect and act upon emotions, in multiple time frames and from diverse perspectives. In combination with imagination, this becomes a powerful tool. In “The Good Ancestor,” Roman Krznaric7 offers inspiring and practical ways of reflecting on and taking sustainable action; his ideas about planning for the future inspired me to examine possible relationships between contemplation (reflection and imagination) and meaningful engagement (caring action, i.e., community building and conservation).

Present action and the past

© Anaïs Pachabézian

- Contemplation of (imagining and reflecting on) stories about who we were, what we knew, and how we lived, to help us meaningfully engage with others and our world.

- Reflecting on (contemplation of) past caring action (engagement) from the perspective of who we are and how we live today.

Present action and the present

- Contemplation of (imagining and reflecting on) stories about who we are, what we know, and how we live today, to help us meaningfully engage with others and our world.

- Reflecting on (contemplation of) caring action today (engagement) from the perspective of who we are and how we live today.

Present action and the future

- Contemplation of (imagining and reflecting on) stories about who we want to become, what we want to discover, and how we want to live, to help us meaningfully engage with others and our world.

- Reflecting on (contemplation of) possible future caring action (engagement) from the perspective of who we are and how we live.

Each of these possible scenarios has its own narrative and can offer opportunities for empathy-building, especially if the “we” is examined from the viewpoint of different stakeholders. Engagement and contemplation, together with imagination and creativity, can work together to support us in learning from history, assessing our present, and imagining and planning for our future. We may believe that how we live today defines who we are and who we have always been. We may even think of aspects of our past in terms of legacy and heritage if it suits us, and reject or ignore others. If we include more stories in our curriculum from different perspectives about how our societies came to be—e.g., contemplation of (imagining and reflecting on) stories about who we were, what we knew, and how we lived, to help us meaningfully engage with our world and others—we are more likely to build a more inclusive society. With reference to the value of history in Britain, Neil MacGregor, art historian and former Director of the British Museum, states, “I don’t think it’s valued enough… we don’t give it the same place (as Germany) in our schools and I don’t think we examine enough our past in order to understand properly our present.”8

© Anaïs Pachabézian

Looking back at books I read many years ago reminds me of the person I was when I read them. I may have changed, but reading continues to nourish and motivate me. It offers me ways of examining a range of experiences, both positive and negative. We can use the emotions, engagement, and contemplation that comes from the act of reading to foster more sustainable ways of thinking and living. Anne Michaels comments, “I think we have to practice doing the right thing and literature is really a fantastic place to practice that, to exercise that muscle.”9 By designing storytelling that inspires connection and care more explicitly into our curriculum, and role modeling how empathy can be translated into action, we could impact how we live and who we want to be. Combining the power of language, real and imagined experiences, nature and creativity in a robust equation can help us find new stories to address the challenges humans and non-humans face together.

© Anaïs Pachabézian

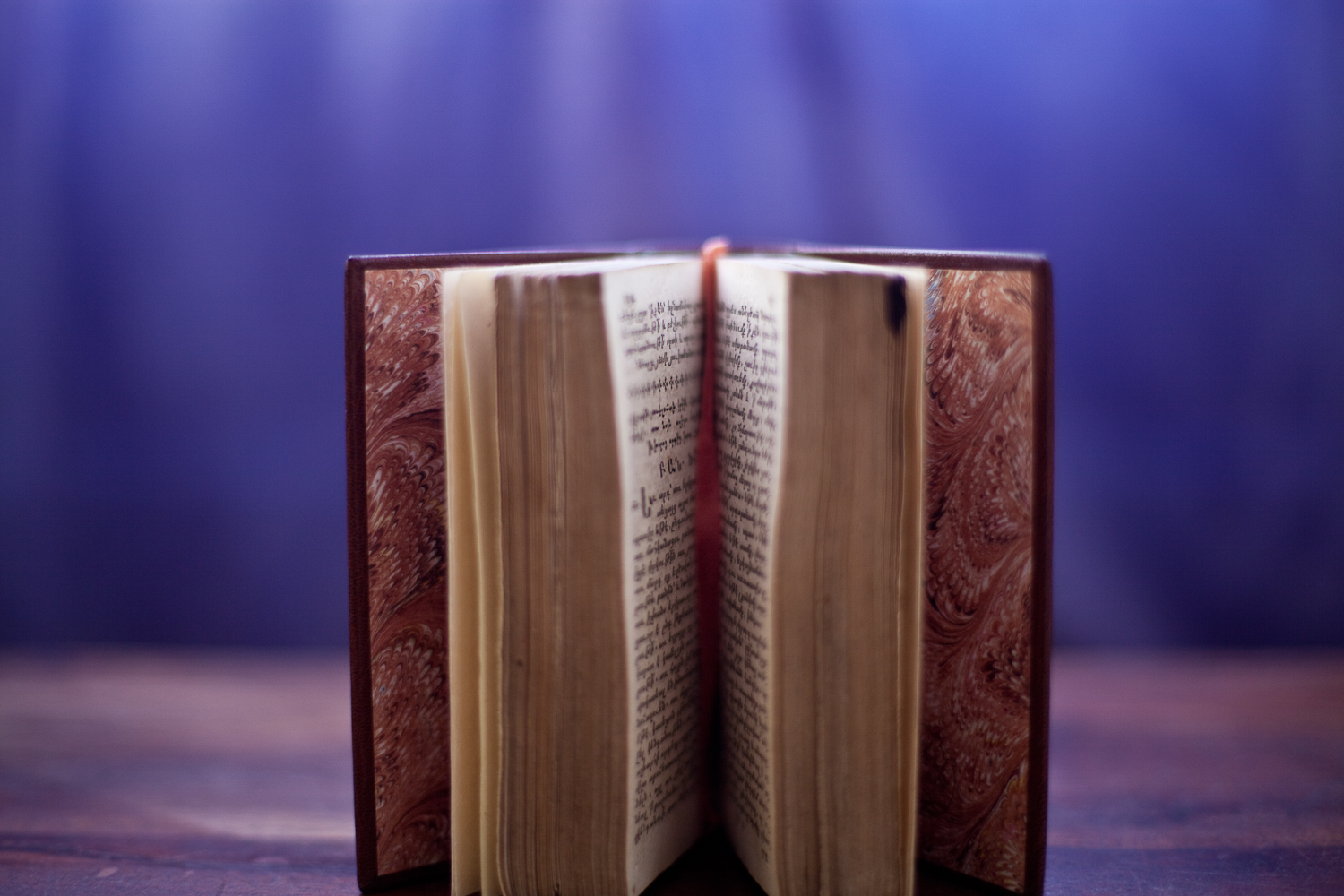

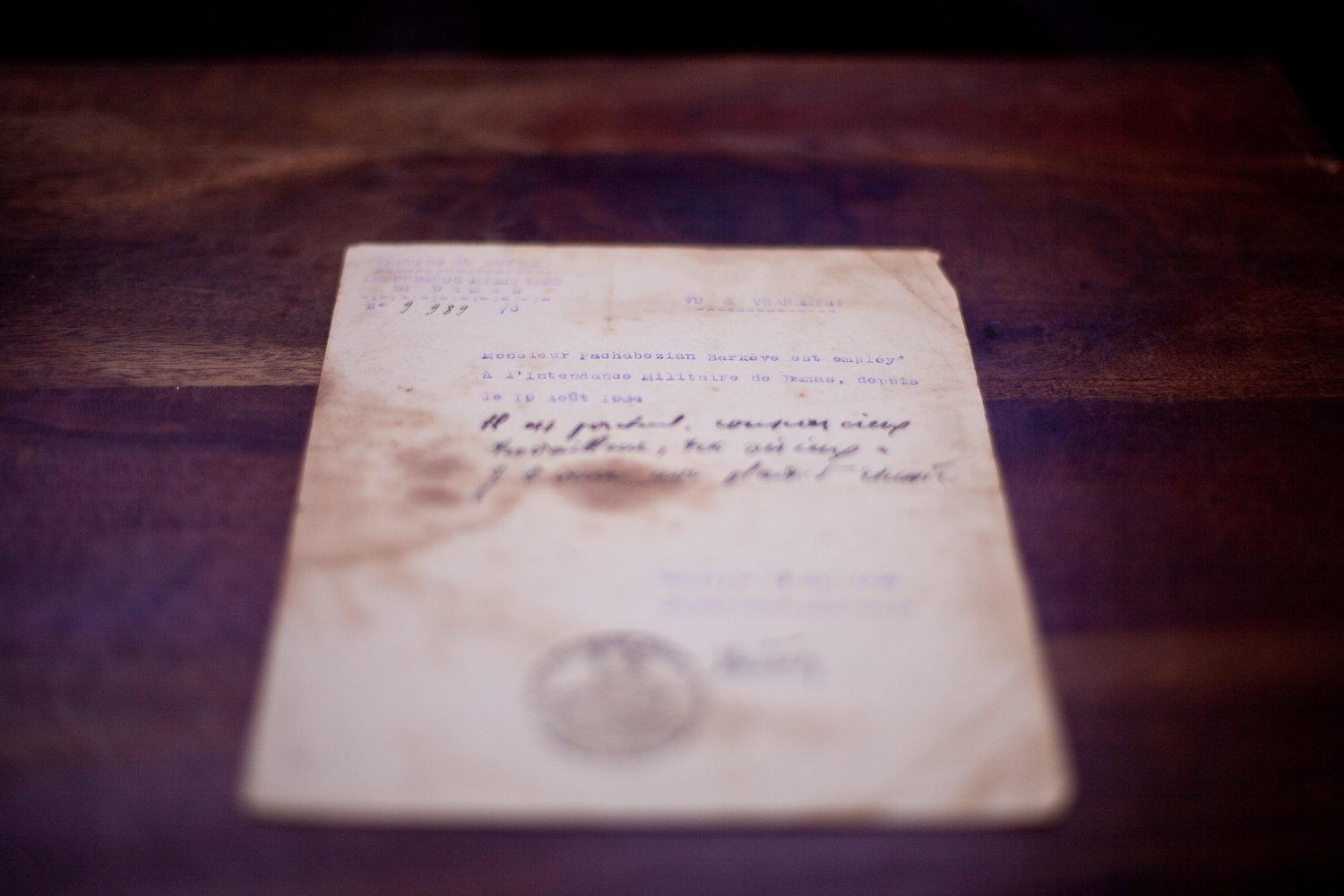

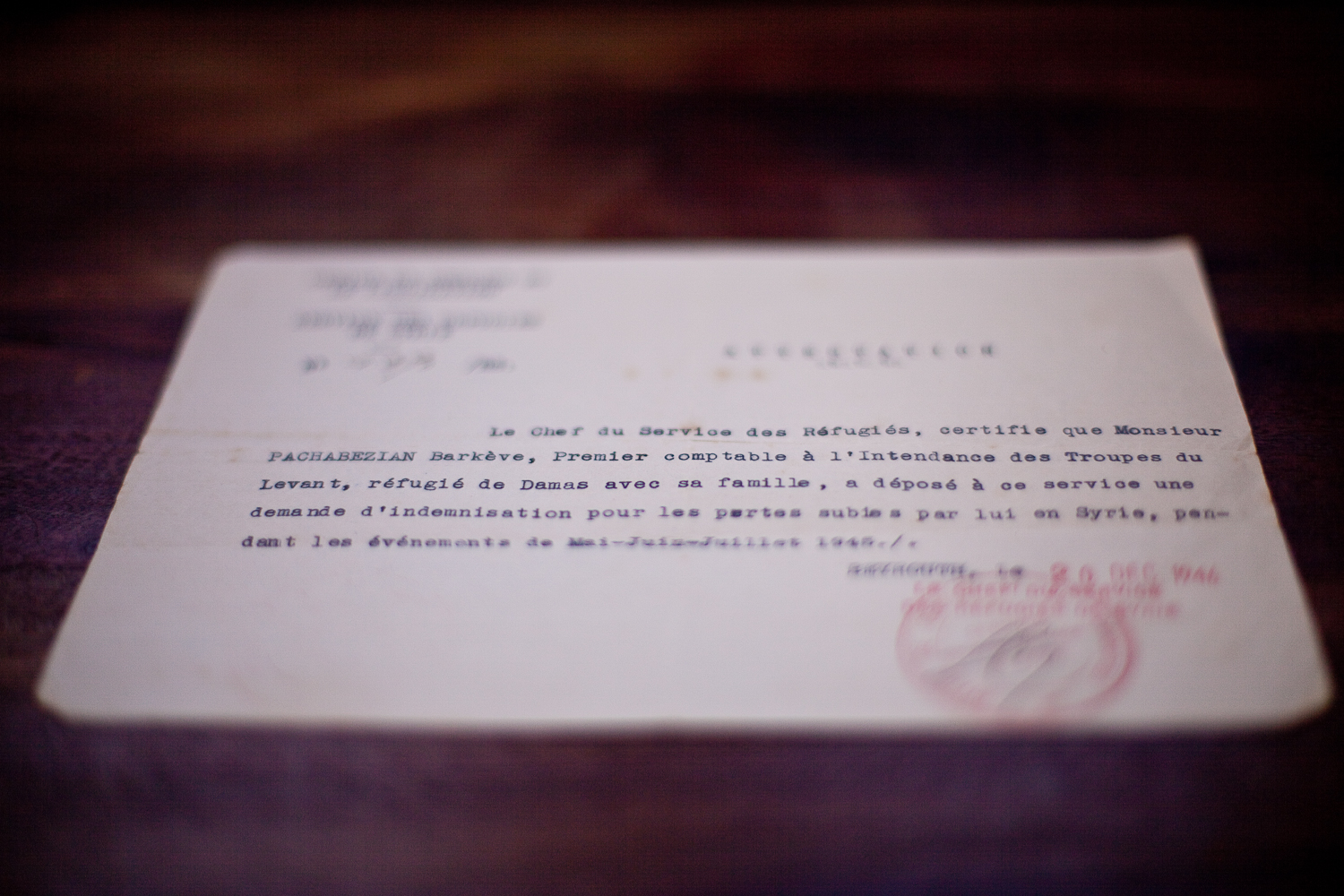

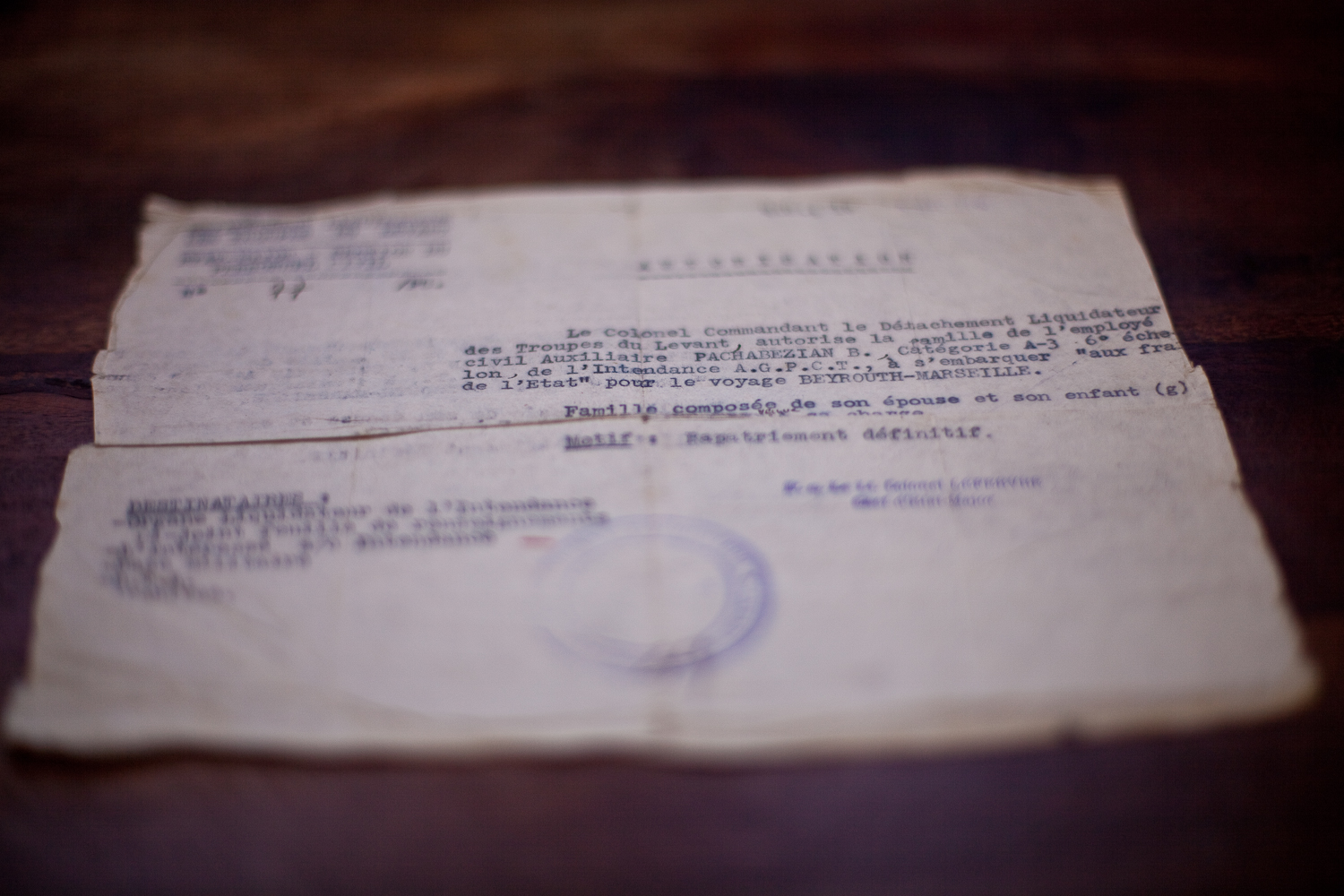

Little family inventory by photographer Anaïs Pachabézian

I am Armenian through my father. My great-grandmother with her three sons fled the genocide and the south present-day Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century. As refugees in Syria, my grandparents married in Damascus and then lived in Lebanon before emigrating to France.

My father was born in Beirut in 1946, a few months before boarding a boat to Marseille, with my grandparents who had just become French citizens.

For twenty years, I have been trying to put together the pieces of the puzzle of this history. This small family inventory is the beginning of a response to the reconstruction of this story, where the objects assembled speak in some way of a moment of this family novel.

Gathering these objects allows me, through appropriation, to better understand this family history and try to unveil mysterious parts of it. By following the traces of the past and by questioning these fragments, I try to fill in the gaps: to reconstitute the family history and to find answers to the yet unsolved questions.

Consequently, this series of nine photographs represents the beginning of an inventory (a work in progress) gathering some objects and documents belonging to me or to my father and my uncle.

References

1Cressida Cowell, “‘Libraries Change Lives’ : Lire la lettre ouverte de Cressida Cowell au Premier ministre Boris Johnson”. Book Trust : Getting Children Reading, 13 avril 2021, www.booktrust.org.uk/news-and-features/features/2021/april/libraries-change-lives-read-cressida-cowells-open-letter-to-prime-minister-boris-johnson.

2George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain : In Which Four Russians Give a Masterclass on Writing, Reading, and Life. Londres : Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021, 19

3Sarah Mears, “L’empathie peut-elle s’apprendre ?” Books2All, 28 mai 2021, books2all.co.uk/blog/2021/05/can-empathy-be-learnt/.

4Le Centre for Language, Culture and Learning de l’université Goldsmiths accueille Philip Pullman “en conversation” avec Michael Rosen, le vendredi 21 mai 2021. https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/philip-pullman-in-conversation-with-michael-rosen-tickets-148347283719?aff=ebdsoporgprofile

5Hannah Critchlow, The Science of Fate : Why Your Future is More Predictable Than You Think. Londres : Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, 2019, 111

6Robert MacFarlane, Landmarks, Penguin, 2015, 237

7Roman Krznaric, The Good Ancestor : How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World. Virgin Digital, 2020, 102. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Good-Ancestor.

8Nihal Arthanayake anime Neil MacGregor avec Nihal Arthanayake, The Penguin Podcast (podcast audio), 16 février 2021, consulté le 2 mai 2021. https://play.acast.com/s/thepenguinpodcast/neilmacgregorwithnihalarthanayake

9Bidisha accueille Anne Michaels et Bidisha : The Necessary Word, London Review Bookshop Podcast, 20 janvier 2021, consulté le 5 avril 2021. https://play.acast.com/s/londonreviewbookshoppodcasts/annemichaelsandbidisha-thenecessaryword

Sara Riaz Khan is a visual artist and educator. In her art practice, Sara explores ideas about transformation, a common humanity, and our connection to nature. She has supported community art projects, hospital outreach, disaster relief and literacy initiatives, taught Middle Years Program art and design and been a school artist-in-residence. As a Director at Harbord and Khan Educational Consultants, Sara develops ethical curriculum and has co-authored two International Baccalaureate resources ‘Interdisciplinary Thinking for Schools: Ethical Dilemmas MYP 1, 2 & 3’ and ‘Interdisciplinary Thinking for Schools: Ethical Dilemmas MYP 4 & 5’ (Harbord and Khan, 2020).

For the past fifteen years, Anaïs Pachabézian has been building a photographic body of work around tales where individual and collective histories are mixed. The notion of displacement (voluntary or forced) is at the heart of her projects. She is also interested in trauma, resilience and more recently in questions of intergenerational transmission. She mainly uses photography, although video and sound are also part of her practice to try to capture what is revealed in the emptiness. In parallel to these works, she carries out commissions and intervenes with various audiences during artistic practice workshops. She is also working on a documentary film project (grant Brouillon d’un rêve SCAM) where she is interested in her Armenian family origins.

Sara Riaz Khan is a visual artist and educator. In her art practice, Sara explores ideas about transformation, a common humanity, and our connection to nature. She has supported community art projects, hospital outreach, disaster relief and literacy initiatives, taught Middle Years Program art and design and been a school artist-in-residence. As a Director at Harbord and Khan Educational Consultants, Sara develops ethical curriculum and has co-authored two International Baccalaureate resources ‘Interdisciplinary Thinking for Schools: Ethical Dilemmas MYP 1, 2 & 3’ and ‘Interdisciplinary Thinking for Schools: Ethical Dilemmas MYP 4 & 5’ (Harbord and Khan, 2020).

For the past fifteen years, Anaïs Pachabézian has been building a photographic body of work around tales where individual and collective histories are mixed. The notion of displacement (voluntary or forced) is at the heart of her projects. She is also interested in trauma, resilience and more recently in questions of intergenerational transmission. She mainly uses photography, although video and sound are also part of her practice to try to capture what is revealed in the emptiness. In parallel to these works, she carries out commissions and intervenes with various audiences during artistic practice workshops. She is also working on a documentary film project (grant Brouillon d’un rêve SCAM) where she is interested in her Armenian family origins.