A year before the dystopic outbreak of a global pandemic, an ongoing situation that has taken its toll on numberless lives while restricting millions of people to their homes, a group exhibition inspired by Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own was presented in Greece, exploring the concepts of room and creativity in secluded spaces. The Voyage Around My Room exhibition, conceived and curated by PhD candidate Kika Kyriakakou, opened on March 18, 2019 in the Municipal Art Gallery of Athens, as part of the UNESCO Athens World Book Capital program. Kyriakakou invited a diverse range of visual artists, writers, and academics, including Jonas Mekas, Sylvere Lotringer, Sophia Al Maria, Juliana Juxtable, and Amalia Ulman, among others, to reflect on the notions of room and confinement in relation to their artistic practices.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

In 1929, Virginia Woolf pointed out the importance for an artist of having a personal, creative space and a regular income with the above sentence in A Room Of One’s Own, one of the most influential essays of feminist literary criticism (Moran, 2001: 477). Woolf’s comments have received a lot of praise, inspiring writers, artists, and readers all over the world. According to Jianjun (2010: 47-48), the essay has become “the inspirational source for the fundamental queries of a female literary tradition and the historicized, politicized and gendered second wave women’s movement in the last century, and is also much appreciated in the present post-modernist or post-feminist time”. In 2019, the Voyage Around My Room exhibition, inspired by Woolf’s essay, reflected upon personal space in the 21st century, alluding, at the same time, to Xavier de Maistre’s 18th-century book of his voyage around his room, a personal, and rather witty, journal illustrating how somebody could overcome space restrictions in a creative and constructive manner.

The show’s primary intention was to openly address contemporary notions such as private space in the 21st century, digital feminism, queer art, and the #metoo movement, and their relevance to the gender equality movement and current artistic processes. A year later, the exhibition, dedicated to the concept of the room and the confinements and restrictions it invokes, would acquire additional readings and references due to the unprecedented conditions of global lockdowns and self-quarantines.

The room in the social media era

Private and intimate moments are now instantly uploaded and shared through social media. Walter Benjamin’s era of mechanical reproduction has evolved into a meta universe of selfies, reality shows, and virtual living, revealing new perspectives and constant changes in peoples’ relationship with public space and sharing, AI and technology. Overexposure, narcissism, and objectification prevail online while everyday life is shared in the privacy of everyone’s room.

The room as connotation for self-expression and equality

Escape from closeting, borders, bias, dogmatism, and patriarchy are concepts interwoven with the contemporary discourse on LGBTI+, women’s movement, and human rights struggles. Almost a century after the publication of Woolf’s essay, the room still stands as a symbol of individual freedom and financial independence, underlining the necessity for diversity, egalitarianism, and non-discrimination in modern societies.

The room as a collection space and an artist’s cabanon

From wunderkammers to artists’ studios, the room has always borne a personal validity, often reflecting the personality, intellect, creativity, empathies, and obsessions of its owner. Beyond its physicality, the artist’s room functions as an allegory of memory, of personal identity and body, of artistic expression, and the need for escapism and travel.

Space, room, privacy, and isolation—further literary allusions and references

Personal space in literature and art will often bear dual dynamics and interpretations. In one respect, the room can be idealized as an area in which writing and creativity can evolve in the way it is depicted in Woolf’s essay. From Thoreau’s Walden (1854) to Susan Sontag’s The Volcano Lover (1992), personal space has been exemplified either as a way of getting closer to nature and to our primary instincts and purposes, or as a means to perpetuate our personal perseverance through collecting and creating distinctive cabinets of curiosities.

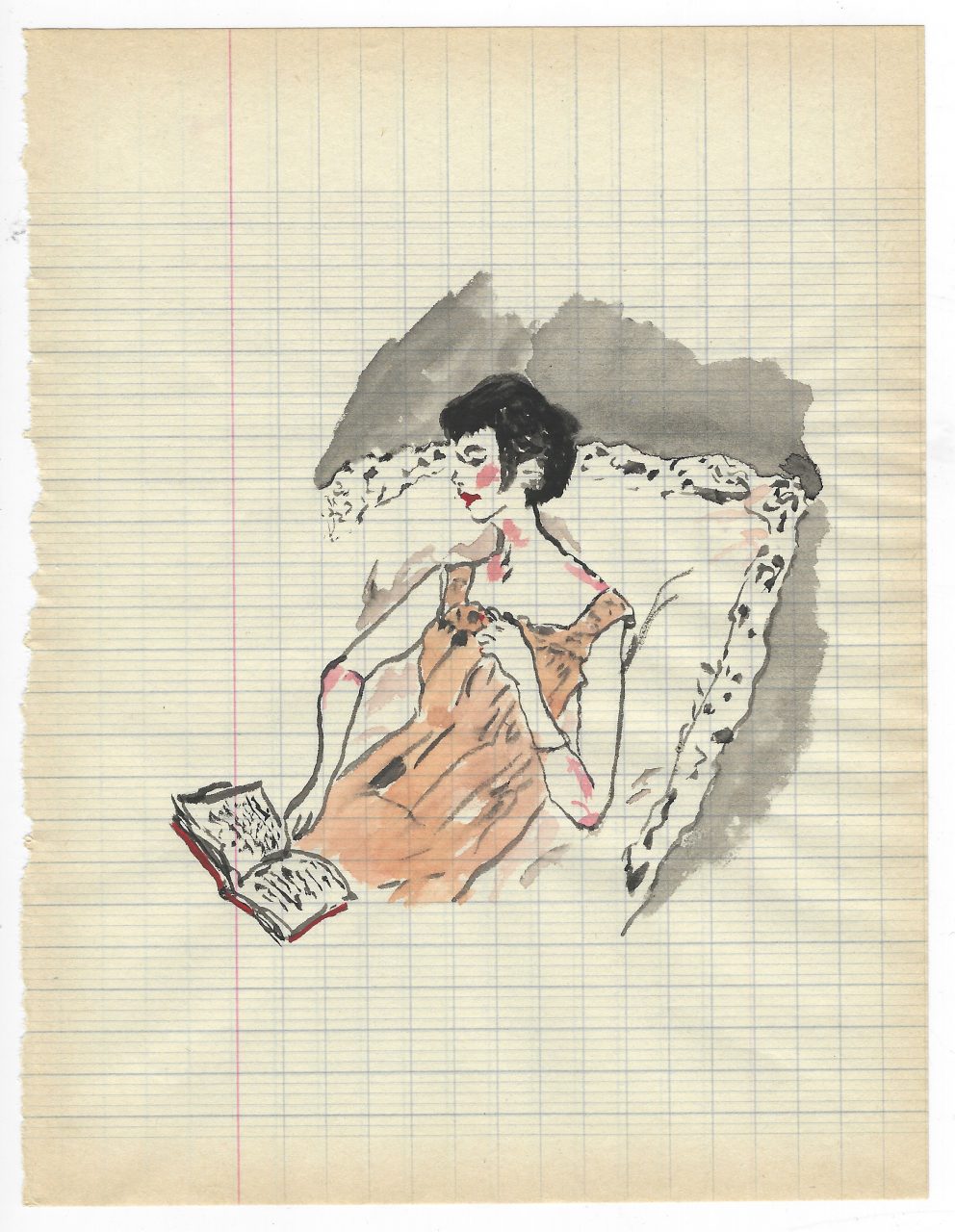

Sharon Kivland, Liseuse de Capital (2019) detail, courtesy of the artist. Voyage around my Room exhibition (2019), Athens.

However, the concept of home and personal space has not always been idealized. In A Doll’s House (1879), Henrik Ibsen expresses how the Victorian home, and Western, 19th-century societies in general, were nothing more than places of confinement and restrictions, deeply rooted within patriarchal structures and stereotypes. Nora Hemler, Ibsen’s renowned feminist heroine, transcends housewifery to achieve independence and self-awareness—an unexpected scenario in a theatrical work that caused much controversy amongst audiences at the time.

In the 1970s, artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro decided to approach the notion of house, private space, and room in a different, more communal manner, as the times demanded. During the first project of the California Institute of the Arts’ Feminist Art Program, titled the Womanhouse, the two artist/educators, along with a number of their students, took over a dilapidated building and turned it into one of the first all-female expressions of art. Womanhouse was an exemplary instance of feminist art within the house, of the notions of domesticity and space in art as well as a to-the-point institutional critique regarding women artists and their exclusion from the art establishments of the time.

In the dawn of the fourth wave, feminist artists once again decided to address unresolved women’s rights issues, like the ones brought up by Linda Nochlin in her 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” With the recent emergence of the #metoo movement and the widespread sociopolitical turbulence deriving from systemic oppression and marginalization, artists are reevaluating their roles, missions, and language. Though almost a century old, Woolf’s essay still proves relevant to what is occurring in the world today, resonating, to a great extent, with contemporary discourses on arts, gender identity, and politics.

Amalia Ulman Privilege 5.4.2016 (2016), courtesy the artist, Arcadia Missa, London and Deborah Schamoni, Munich. Voyage around my Room exhibition (2019), Athens.

The Voyage Around My Room exhibition—artworks and connotations

During the Voyage Around My Room exhibition in Athens, all fourteen participating artists and writers were asked to address key notions of the A Room Of One’s Own essay through their work, using media ranging from assemblages, installations, drawings, sculptural pieces, and texts to videos and online works. All artworks functioned as collective comments on the notion of room and Woolf’s feminist legacy, while addressing topics like gender stereotypes, private space and time, domesticity, adolescent angst, isolation, as well as interpersonal relations and public identity in the social media era.

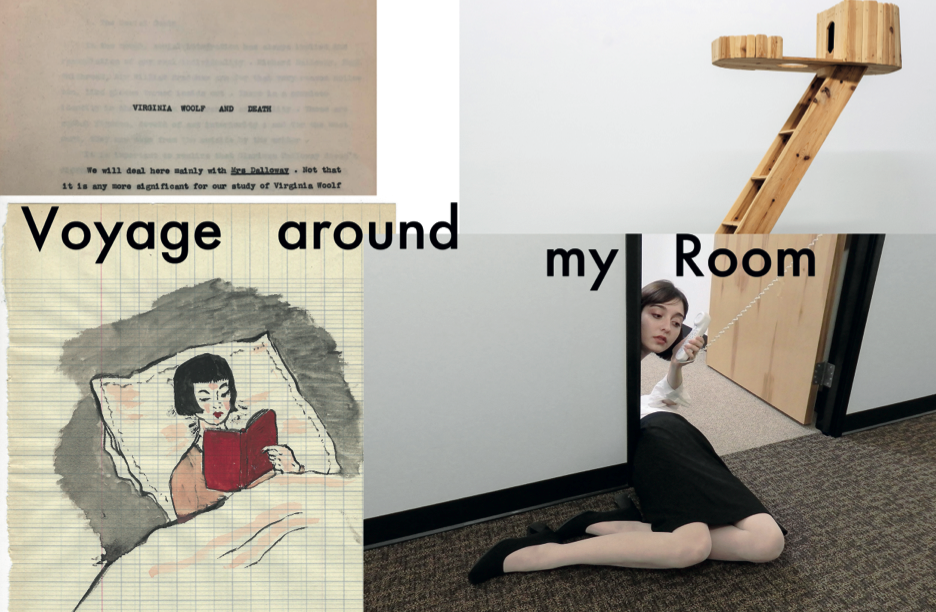

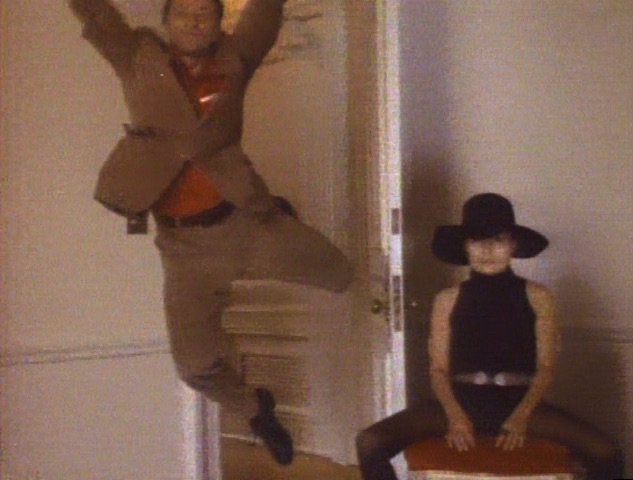

On the occasion of the show, poet and artist Jonas Mekas, known as the godfather of American avant-garde cinema, presented his 365 Day Project, a website composed of 365 individual videos posted daily throughout 2007. Long before Snapchat, Instagram stories, and Facebook Live, the renowned cinematographer had decided to share his everyday moments online on a daily basis, sometimes in the privacy of his own room. Visual artist Dimitris Ioannou created a display of 1/35 scale modelist bunkers, under the title “Back in the days when I was a teenager, Before I had status and before I had a pager” (2019), a sculptural installation reflecting upon adolescence and isolation, often occurring in a space that it is not our own. Writer and artist Sharon Kivland produced an installation titled “Liseuses De Capital” (2019), a contemporary reflection on women reading in their bedrooms and boudoirs, and their political and social concerns. Visual artist Dora Economou created a large-scale ceramic display titled “Cracker” (2019), a series of stoneware pieces resembling the forms and veins of leaves, alluding to the wrongly-presumed fragile female character.

Visual artist Kostis Velonis’ sculptural piece, “How to guarantee conditions of contemplation to the older feline population (‘pet sculpture’ series)” (2016), commented on the relationship between privatization and the public sphere with gender connotations. His kitten-house sculpture is based on an unrealized speaker’s platform designed by El Lissitzky for Lenin. The cat, a domestic symbol of privacy and female objectification, is requested to adapt to a new living space, a platform traditionally designed for public speeches and alpha male political beings.

Visual artist Juliana Huxtable’s work “Untitled (For Samuel)” (2012) was a comment on alienation and sexism in video games, often played in the privacy of one’s bedroom, and her experience of boyhood as a transgender woman. Director and academic Eva Stefani presented The Box, a film that narrates the life of a seemingly isolated old lady in her apartment—a lonely woman whose only friend appears to be a TV news spokesman that she reverently watches every night in her “box.”

Juliana Huxtable, installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

Sharon Kivland, installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

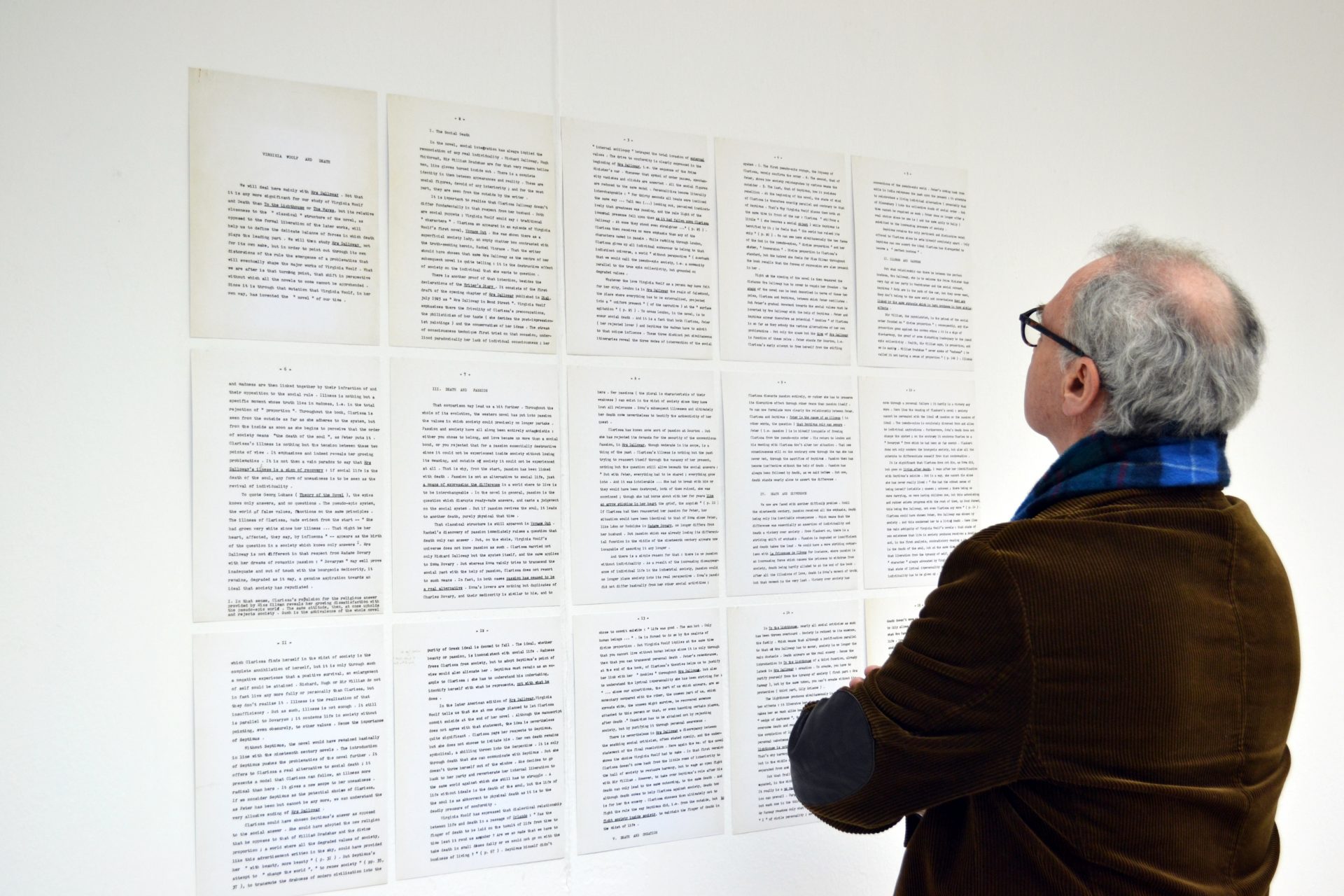

Silvere Lotringer, installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

Sophia Al Maria, installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

Dora Economou (back) and Theodoros Chiotis (front), installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

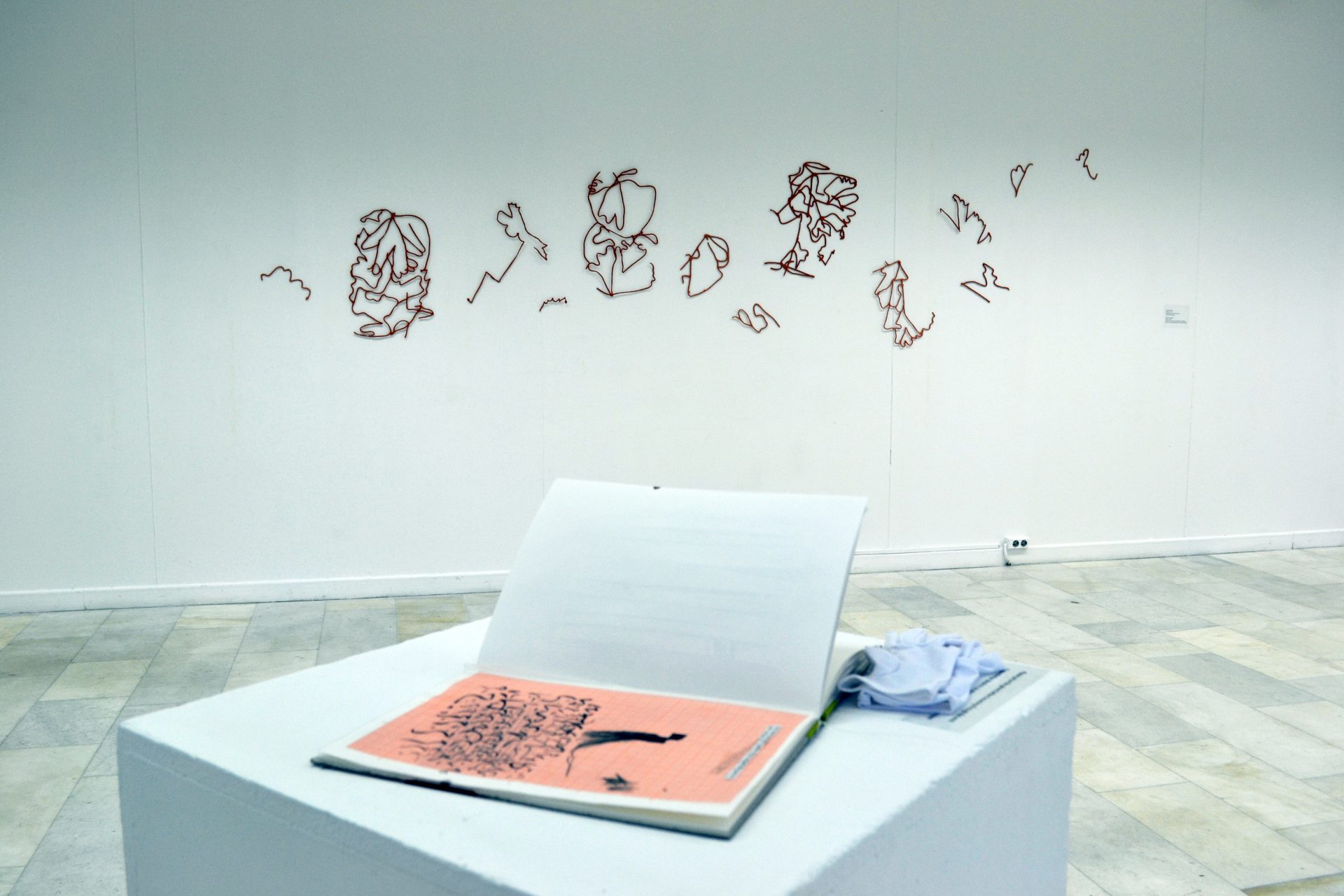

Maro Michalakakos (back) and Philomena Epps (front), installation shot, Voyage around my Room exhibition, 2019, UNESCO-Athens World Book Capital Program

Artist and writer Sophia Al Maria participated with “The Magical State” (2017). In this allegorical work, the protagonist, a teenage girl from the indigenous Wayuu tribe in Colombia, is being possessed by an ancient, wicked spirit. The girl addresses the excessive environmental and social exploitation in the land of her ancestors, and releases her wrath against every form of oppression while spreading a strong feminist message. Poet Theodoros Chiotis reapproached Woolf’s essay through his work “A Data Set of One’s Own (Tuesday)” (2019), an assemblage of cut-out phrases, materials, drawings, and extracts of the original text written in asemic, a wordless open semantic form of writing that is left for the reader to interpret. Visual artist Amalia Ulman presented “The Future Ahead—Improvements for the further masculinization of prepubescent boys” (2015), a video essay focusing on the online rumors of Justin Bieber’s supposed gender transition. Amalia’s piece explores how social media affect our perception of gender, masculinization, and teenagehood while alluding to Paul Preciado’s Testo Junkie (2008) and Bernadete Wegenstein’s Cosmetic Gaze (2012), among other works.

Writer, academic and founder of Semiotexte, Sylvere Lotringer, while a university student in 1969, and under the supervision of Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann, decided to dedicate his thesis to Virginia Woolf and her room. The result is an essay titled “Virginia and Death” (1969), presented as a wall display in the show in its original format, a typewritten work reminiscent of Lotringer’s early encounter with Woolf and her effect on his practice. Visual artist Maro Michalakakos’ mirror sculpture, titled “Dear Prudence” (1996) focuses on dominant perceptions regarding the female gender. Its reflection on red velvet featured just two hands in a shy, prudent gesture—personality characteristics often falsely attributed to women. In 2014, art writer Philomena Epps created “Orlando” (2014-ongoing), an independent publication focusing on visual arts and their intersections with cultural criticism and sociopolitics. The name derives from Woolf’s transgressive protagonist, and signals a particular investment in feminist and queer politics. During the show, “Orlando” was displayed as an art piece, an allusion to magazines and feminist publications functioning as an alternate art form. Finally, on the occasion of the exhibition, writer, curator, and artist Jeanne Graff was invited to address Woolf’s primary notions through her multidisciplinary practice. Graff’s work resulted in an untitled grid of notes, booklets, sounds, and images, a personal display of objects and narratives much reflecting her microcosmos as an independent female creatrice.

References

Benjamin, Walter. “Illuminations.” In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Edited by Arendt, Hannah. London: Fontana, 1968. First published in 1935.

Ibsen, Henrik. “A doll’s house.” New York: Dover Publications, 1992. First published in 1879.

Jianjun, MA. “Virginia Woolf’s Aesthetics of Feminism and Androgyny: A Re-reading of A Room of One’s Own”, Comparative Literature: East & West, 13:1, (2010): 47-59.DOI:10.1080/25723618.2010.12015582

Maistre, de Xavier. “Voyage around my room”. New York: New Directions, 2016. First published in 1794.

Moran, Patricia. “Cock‐a‐doodle‐Dum: Sexology and a room of one’s own”, Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30:4, (2001): 477-498

DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2001.9979391

Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” London: Thames & Hudson, 2021. First published in 1971.

Preciado, Paul. “Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era”. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2013. First published in 2008.

Sontag, Susan. “The Volcano Lover: A Romance.” London: Picador, 2004. First published in 1992.

Thoreau, Henry David. “Walden.” London: London Vintage, 2017. First published in 1854.

Wegenstein, Bernadette. “The Cosmetic Gaze: Body Modification and the Construction of Beauty”. Massachusetts: the MIT Press, 2012.

Woolf, Virginia. “A Room of One’s Own.” London: Penguin Classics, 2014. First published in 1929.

Kika Kyriakakou is the artistic director of PCAI (pcai.gr) and the curator of the PCAI Contemporary Art Collection. She is a PhD candidate (University of Athens) with a wide experience in curating, producing and managing contemporary art exhibitions and cultural projects on sustainability, moving image and gender partnering with ART21 NYC, Unesco – Athens World Book Capital, Loop Barcelona and Kunstlerhaus Vienna, amongst others. Kyriakakou has been an arts editor, curator and cultural manager for more than twelve years, writing about contemporary art and film for the Art newspaper (Greek edition), as well as other media. She is a member of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and a nominator for the Earthshot Prize awards. She has been a mentor for the the 2nd Culture Hackathon organized by the British Council and Google in Athens and a member in the Loop Barcelona Discover award advisory committee.

Kika Kyriakakou is the artistic director of PCAI (pcai.gr) and the curator of the PCAI Contemporary Art Collection. She is a PhD candidate (University of Athens) with a wide experience in curating, producing and managing contemporary art exhibitions and cultural projects on sustainability, moving image and gender partnering with ART21 NYC, Unesco – Athens World Book Capital, Loop Barcelona and Kunstlerhaus Vienna, amongst others. Kyriakakou has been an arts editor, curator and cultural manager for more than twelve years, writing about contemporary art and film for the Art newspaper (Greek edition), as well as other media. She is a member of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and a nominator for the Earthshot Prize awards. She has been a mentor for the the 2nd Culture Hackathon organized by the British Council and Google in Athens and a member in the Loop Barcelona Discover award advisory committee.