At the end of 1930, “color photography for all” makes its entrance. The expression is not random. It is theatrical, and suggests a profound change in the photographic perception of the world.

From black-and-white to autochromes, up until the early 1900s, emulsions on glass plates mainly allowed what we perceive today as a graphic, evocative, historical representation of common reality. It required technical know-how and the means to afford the capture of this tangible reality. The heavy and cumbersome cameras were fixed on stands. As the exposure of the emulsion to light required several minutes, photographers concentrated on what kept still in order to obtain sharp images—architecture, landscape, space, and set-up portraits. Over time, emulsions became more sensitive to light, therefore easier to use, and film negatives replaced glass ones. Equipped with more malleable and responsive cameras, photographers explored inhabited space, activities in the landscape, industry, and still life outside the studio. Space became the lived-in place, the everyday life.

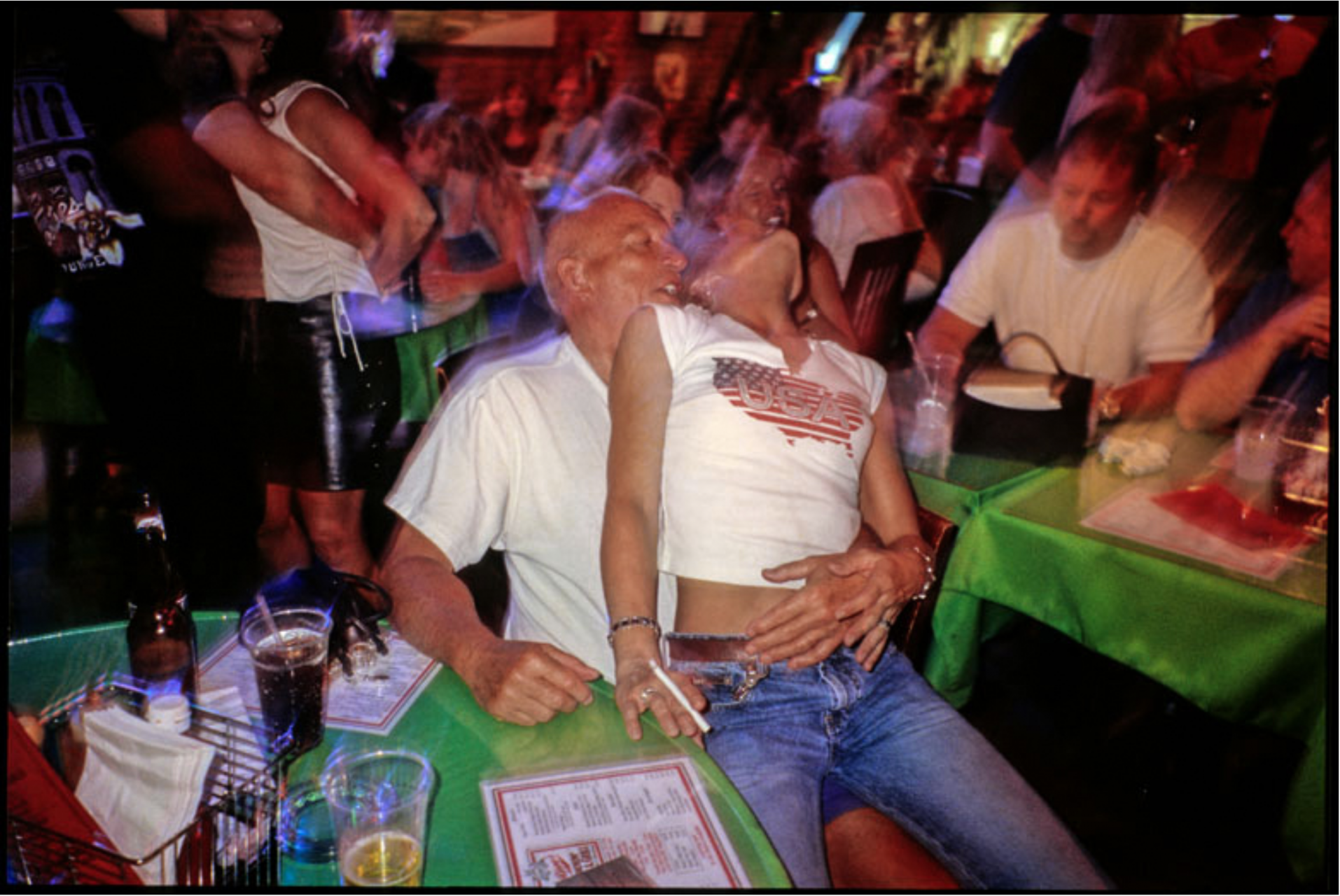

In 1967, “Click-clack, thank you Kodak,” the arrival of the Instamatic camera offers everyone the possibility to photograph everything, all the time, without knowing an ounce of technique. Simply insert a film cartridge, press the button, and the exposure and shutter speed are set automatically. Colour film becomes the predominant medium for capturing the vision of everyday life. It is widely used to photograph special moments—birthdays, holidays, weddings, etc.—abandoning what early photographers, like Eugène Atget, mainly studied, which was space and place. The advent of digital photography has only reinforced this practice. Social networks are overflowing with photos of the day’s activities and minutiae (of wardrobe, meals, events, parties, objects, pets, etc.) to the point that representations of space are struggling to find their place.

The amplification of objects and their heteroclism conceals the nakedness of spaces, steals the first silence of things, harpoons the vision, the hearing, the sensation of the body, prevents the birth of a pleasant, rational urbanity…. It is the development of the taste for accumulation, the piling up of everything and nothing, of all waste. And this is often accompanied by noise, by sounds, as a tireless activity, the very essence of a society that wants to repress the archaic silence of life and the natural aesthetics of places at all costs.

Hassan Wahabi, The Tyranny of the Common, La Croisée des Chemins Editions

Since I began photographing professionally in 1985, I have had the opportunity to approach reality in both color and black-and-white. The subject of the photo or the client’s order dictated the choice of one or the other. The balance between spaces and subjects was important to me, but remained only one of the parameters of the composition. At the time I was living in Los Angeles, a very large city, open on one end to the sea, and where, unlike cities such as Tokyo or New York, thanks to wide streets, spaced, individual houses and, at the time, few tall buildings, the urbanism did not feel oppressive.

Later on I moved to New Mexico. My house was at the end of a dirt road in a canyon. In Santa Fe and the surrounding area, adobe houses carry the colour of the earth. Their corners are rounded. Large openings allow the landscape to enter the house. The interiors reflect the high desert that Georgia O’Keefe, Paul Caponigro, Ansel Adams, Bernard Plossu, and many other artists have transcribed. The architecture thus echoes the landscape with an organic accompaniment. It was there that I perceived how the place fits into the space and vice versa.

Let us consider each being, each plant, each stone as a place. Every place is part of a space, so is the Earth in the Universe. A place that moves or not, but remains whole. Thus, the place presents itself as a structure adapted and adaptable to the space. Space, on the other hand, manifests itself in its fluidity and its changing, even immeasurable, boundaries—the water of a stream, the gusts of wind, the flow of ocean currents, and all emitting sounds that the places and space passes through and contain. It seems to me that space acts on us in a much stronger way than place. We look at, see the place. Space awakens all our senses. One is an inspiration, the other a breath.

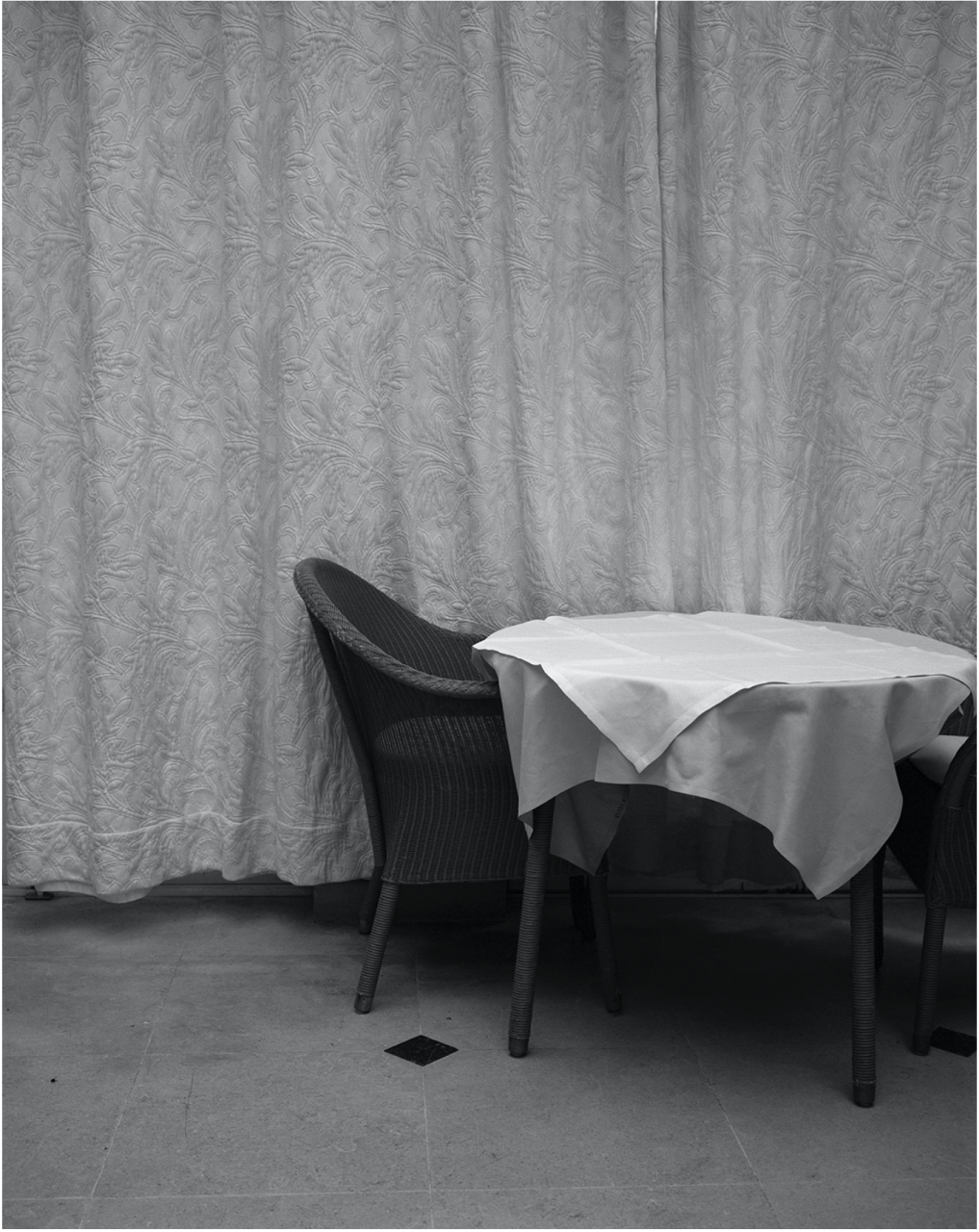

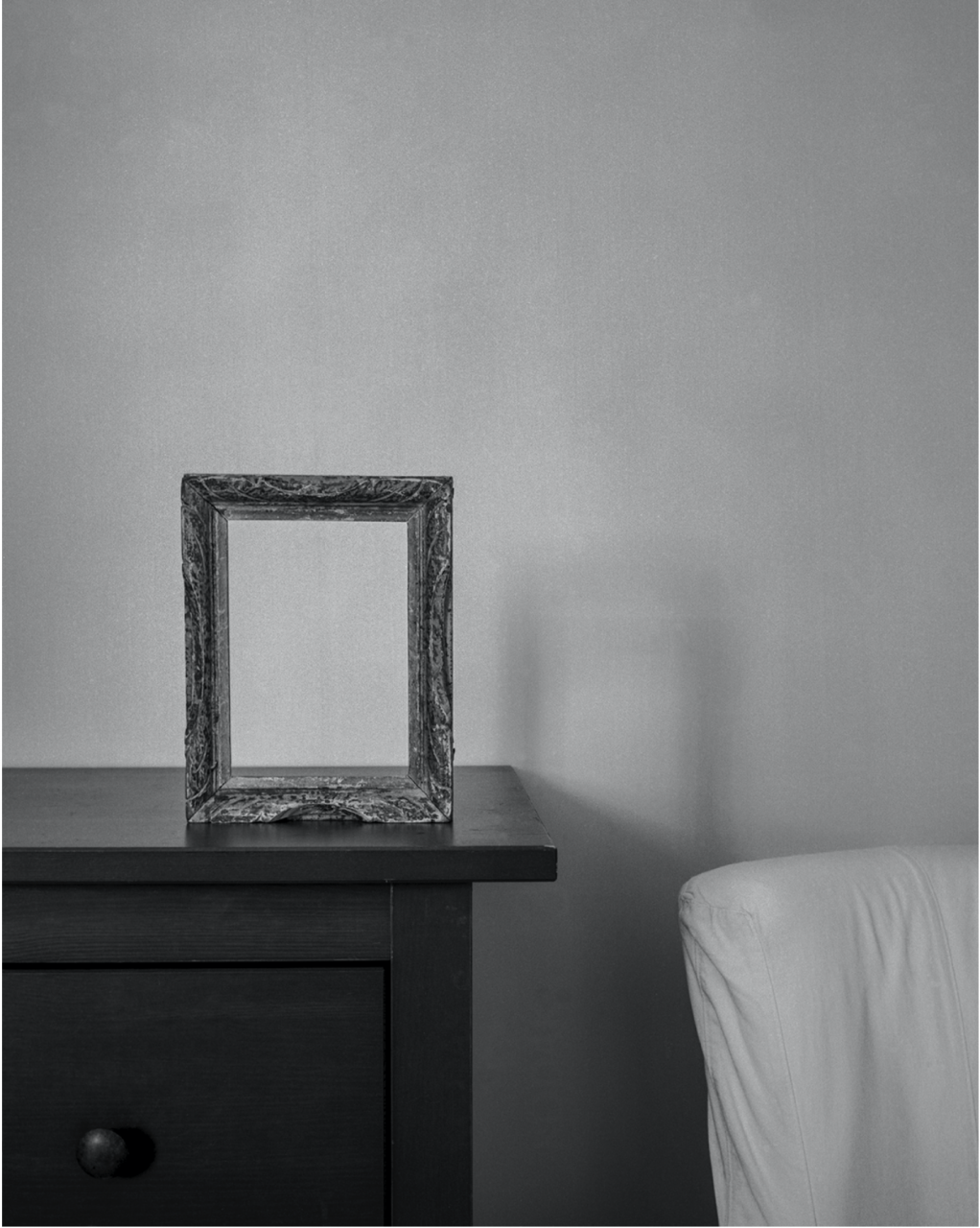

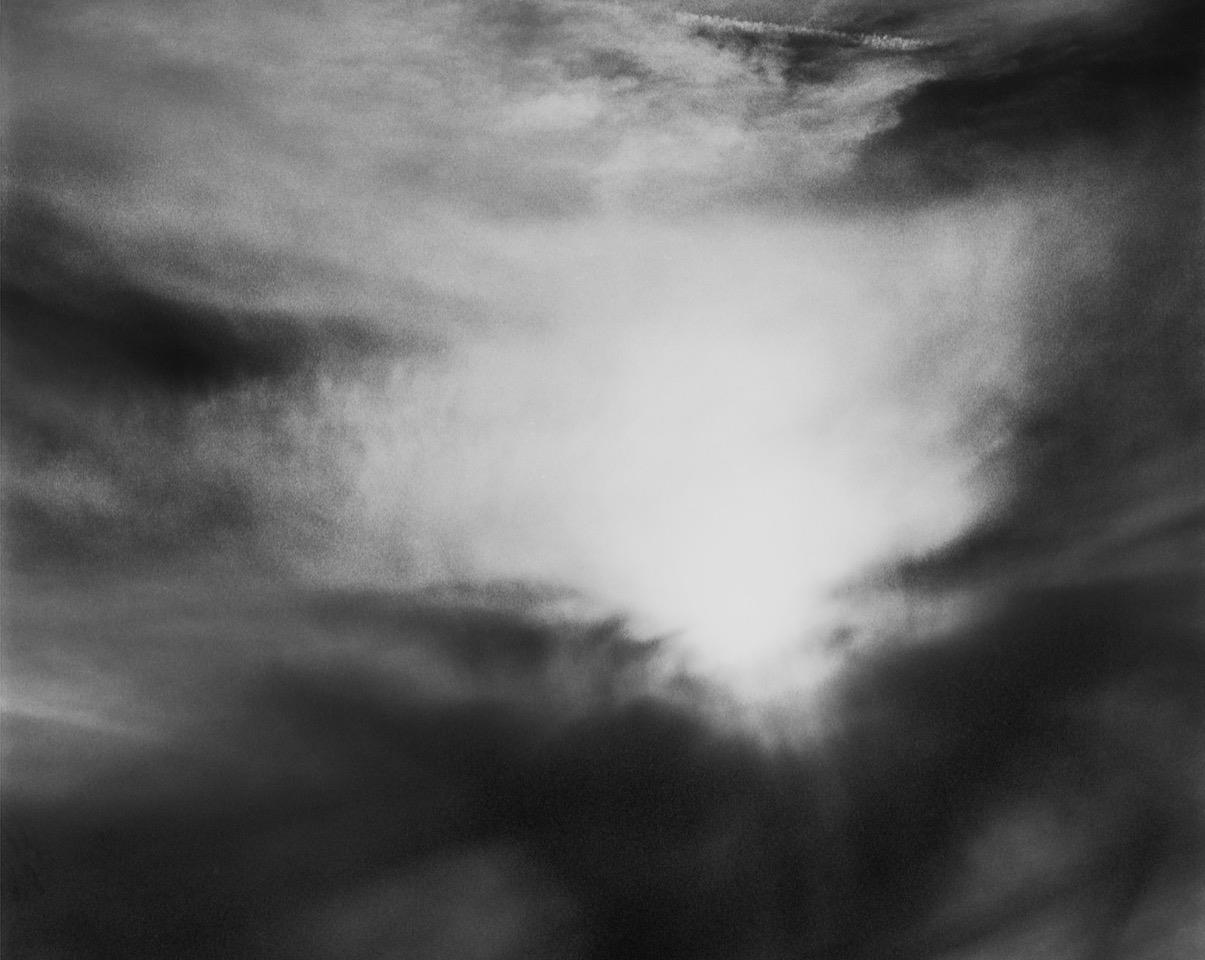

Back in Paris, where the high concentration of the site contrasts radically with the open spaces of the rocky canyons of New Mexico, and where the sky seems lower, I began to look for ways to find that breathing expanse that I had enjoyed so much. After unsuccessfully trying to photograph the space between things—between a chair and a table, between two walls of a semi-detached house, a staircase step and a banister—I opted for a black-and-white photograph. It was necessary to simplify the reading of the image, to free it from its descriptive quality, from the anecdote, which remains so linked to color.

Empty places, damaged, worn objects in these places, evoke a feeling of latency, like a breath—the moment just after the inhalation and the one before the exhalation, when the oxygen enters the blood.

For thus, space contains time, and then becomes itself the time that links all the elements in a fluid and continuous coming and going. In order to accentuate the notion of space/place as a whole, I reduce the contrasts. Without definite black or white, the image becomes softer and allows the eye to take in its totality. The shades of grey reverse our traditional perception of the photographed elements. They are no longer illuminated by a source of light which accentuates their structures, gives them depth, selects and therefore prioritizes areas, drawing our gaze first to the bright spots. In the greyness it is the space, the place, the image itself, that seem to emit light and thus become an indissociable whole.

The colorists pushed their approach to the point of abstraction by treating the photographed subject above all as a support for colour. Weren’t they reconnecting with the notion of space? In continuity with this perspective, it appears I am left with photographing what this low, grey, winter sky creates best—fog. This space where reality becomes timeless, calm, and moving, where the places embody, allow ourselves to be enveloped by the space that contains “the archaic silence of life and the natural aesthetics of places.”

Wouldn’t this mean also recognizing and accepting that we are not the center of the living world, but on the contrary and with joy, that we are one of its inseparable elements?

End of 1979, Michel Monteaux leaves France and begins a career as a professional photographer in Los Angeles. Eight years later, he moves to New Mexico, in the High Desert in Santa Fe. If he continues still life in the studio, he extends his work to portrait and reportage. During these 6 years that he lives close to the Native Americans, embracing their culture. He gets involved in a fight against their precarious situation and also leads – alongside other citizens but also personalities such as Robert Redford – a fight against a gigantic project of landfill of nuclear waste in southern New Mexico. In the mid-1990s, he returnes to France and works for the press (Liberation, Marie-Claire, La Vie, Le Monde, Géo…) but also for large industrial groups (Alstom, ArcelorMittal, Total, Hachette…)

End of 1979, Michel Monteaux leaves France and begins a career as a professional photographer in Los Angeles. Eight years later, he moves to New Mexico, in the High Desert in Santa Fe. If he continues still life in the studio, he extends his work to portrait and reportage. During these 6 years that he lives close to the Native Americans, embracing their culture. He gets involved in a fight against their precarious situation and also leads – alongside other citizens but also personalities such as Robert Redford – a fight against a gigantic project of landfill of nuclear waste in southern New Mexico. In the mid-1990s, he returnes to France and works for the press (Liberation, Marie-Claire, La Vie, Le Monde, Géo…) but also for large industrial groups (Alstom, ArcelorMittal, Total, Hachette…)