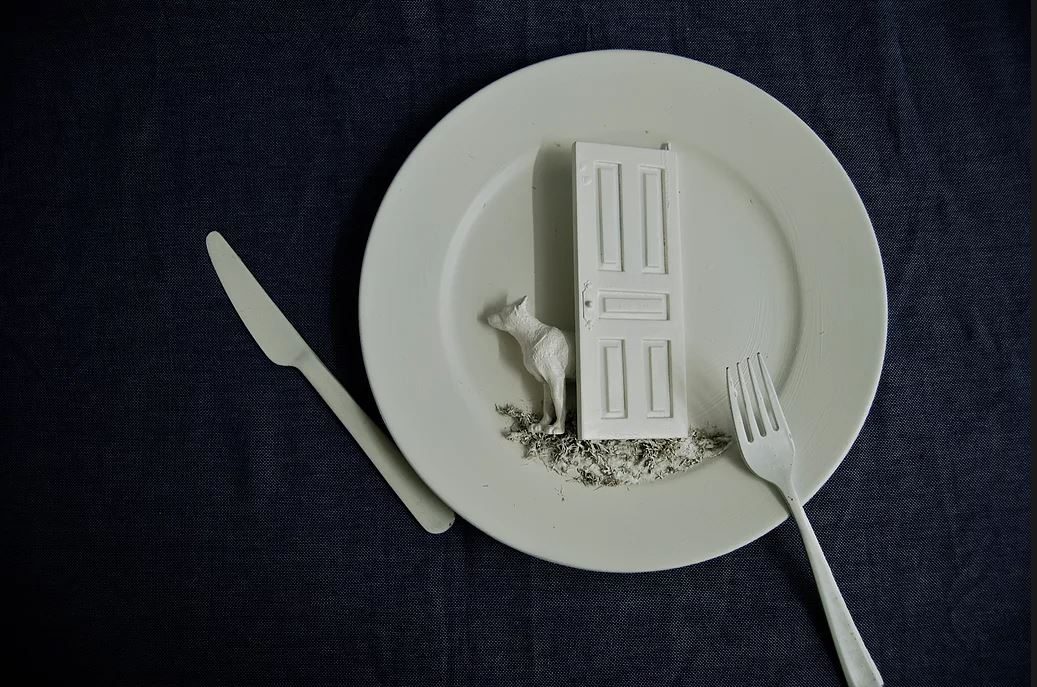

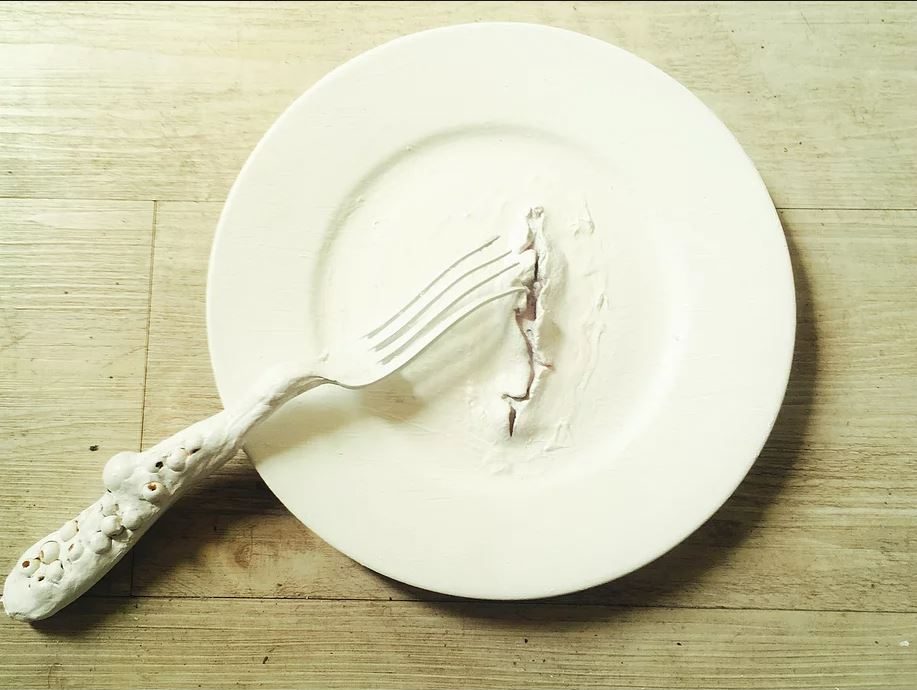

In dialogue with the works of Nadou Fredj

To an unprecedented degree, our age is beset by crises, provoking widespread anxiety about what the future will bring. Does the wisdom of the ages offer a basis for hope? Can philosophy, literature, or the past travails of humanity provide guidance for us today? Let us gather together in a spirit of optimism and reflect upon our situation.

Dinner parties are complex events. Kant, in his Anthropology From A Pragmatic Point Of View, suggests that they provide an ideal venue for the exchange of philosophical views, and are productive of practical solutions, as long as dogmatism is not permitted and, when serious conflicts of opinion occur, that passions not be allowed to run too hot. The environment should be one of conviviality, where reason and mutual respect prevail. When we think of famous dinner parties (at least imaginary ones), we might remember the gathering of eminent women from world history dreamt by Judy Chicago. This dream suggests how the world might have been with different leadership. Are dreams alternate recollections? Do they make us happy or lead us toward understanding the future? Does rational and reflective deliberation, or the wishful reconstructing of history as found in celebratory dinner parties, satisfy our creaturely needs, help us know the good life, or foster hope?

The 21st century is an age of anxiety. Two writers—one Danish, the other Chinese—from other ages of anxiety, though in most respects extraordinarily different, offer perspectives on the human condition which might sound a note of salutary resonance. What might we learn from a discussion with Søren Kierkegaard and Lu Xun?

Imagine a dinner party with the following guests: Constantin Constantius, Frater Taciturnitus, Ah Q, and a Madman. Each guest uses a pseudonym, not only (perhaps not even primarily) because they anticipate acrimonious conflict—although, contrary to Kant’s prediction, there surely will be conflict—but because they lack the authority to speak on their own behalf, and can only play the roles designated for them.

Let us meet the guests. They are the playthings of two masterminds whose authority is clandestine—the authors behind the imposters seated at the table. Two guests are beholden to Søren Kierkegaard and two are bound to Lu Xun, whose name masks another as well. Despite coming from rather different milieus, the guests share several characteristics which might in our time be called personality disorders, or perhaps the consequence of inadequate socialization. They are all social misfits. It is doubtful that they would see it that way, of course—for them, society and its members stand in need of correction. Their alienation, if we insist upon calling it that, is the basis for their held beliefs.

These misfits share other traits as well. They are all beset with anxiety, and they all grasp for a slim reed of hope. In a sense, their hope grows out of their anxiety, and that is the dinner party’s topic for discussion. But let us introduce the guests: Constantin Constantius is the author of a book called Repetition, A Venture in Experimental Psychology, in which he ostensibly seeks to advise a “young man” about his indecisiveness regarding marriage and his decision to break off an engagement. Kierkegaard had something to say about proposals of marriage and the breaking of engagements, but before exploring the theme of repetition, we need to introduce our other guests. Frater Taciturnitus, or the “Silent Brother,” is the author of, among other publications, The Activity Of A Traveling Esthetician and How He Still Happened To Pay For The Dinner. Despite his reticence to speak, his perspective will be important as he represents life in pursuit of beauty and pleasure. The Madman—it is how he refers to himself, not a pejorative designation by Lu Xun—is filled with fear. He sees cannibalism everywhere, and is afraid of being eaten. This is perhaps not the group Kant would have invited, but it is well suited for our topic.

But how can a self-help psychologist, a taciturn monk, a man of unclear origins, and a paranoid diarist contribute to our finding a path from anxiety to hope? Kierkegaard proposes the action of repetition.

The simple idea of repetition is that an act is performed two or more times in a conscious effort to duplicate the original performance, and if possible to improve upon it. It might be an action in the future to recreate the past—back to the future, as it were. However, Kierkegaard’s idea of repetition, as advanced by Constantius, is less straightforward, and represents an approach to what he understood to be an ethical failing in his own life. The scenario developed in Repetition in many ways resembles Kierkegaard’s own broken relationship with Regina Olsen. But where does the idea of repetition come in? Constantius offers the following:

[…] repetition is a crucial expression for what “recollection” was to the Greeks. Just as they taught that all knowing is a recollecting, modern philosophy will teach that all life is a repetition.… Repetition and recollection are the same movement, except in opposite directions, for what is recollected has been, is repeated backward, whereas genuine repetition is recollected forward. Repetition, therefore, if it is possible, makes a person happy, whereas recollection makes him un-happy—assuming, of course, that he gives himself time to live and does not promptly at birth find an excuse to sneak out of life again, for example, that he has forgotten something. (“Repetition,” Essential Kierkegaard, p. 102-103.)

However we interpret these words, they seem to suggest that, rather than pondering eternal truth, anamnesis is replaced by a forward-looking taking back of one’s life. The ethical life is this kind of call to action, not contemplative dithering. Of course, Constantin is being somewhat ironic in seeing this as an embrace of eternal truth.

We find a similar critique of recollection in Lu Xun. In his Call To Arms, he declares:

When I was young I too had many dreams. Most of them I later forgot, but I see in this nothing to regret. For although recalling the past may bring happiness, it at times cannot but bring loneliness, and what is the point of clinging in spirit to lonely bygone days? However, my trouble is that I cannot forget them completely, and these stories stem from those things I have been unable to forget. (“Preface,” Call To Arms, p. 3.)

Both Kierkegaard and Lu Xun see their ages as ones that manifest a crisis of consciousness. For Kierkegaard, it is a profound crisis of religious faith, prompted by official and social pressures and mediated through the Danish State Church. In Lu Xun’s case, the transition from Qing imperial China to the newly-declared, unstable Republic raised questions of identity, loyalty, and even aesthetic preference. In the last category, issues of outward appearance were indicators of loyalty, authority, and the basis for speaking. The crisis may first have become evident to Lu Xun during what is now referred to as the magic lantern incident:

In January of 1906 in the northeastern Japanese city of Sendai, Lu Xu claimed to have experienced a life-changing epiphany that led him to abandon his medical studies and “devote himself to the creation of a literature that would minister to the ailing Chinese psyche.” The now famous “magic lantern (slide) incident” allegedly took place at the end of Lu Xun’s bacteriology class at the Sendai Medical School. The lesson had ended early and the instructor used the slide projector to show various images to students from the recently concluded Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). Lu Xun later recounted that the Japanese medical students were roused into a patriotic frenzy by scenes of the war, culminating in reverberating chants of “banzai!” One scene showed a Chinese prisoner about to be executed in Manchuria by a Japanese soldier and the caption described this man as a Russian spy. Lu Xun reported that rather than the sight of a fellow Chinese facing death, it was the expression on the faces of the Chinese bystanders that troubled him deeply. Although they appeared to be physically sound, he felt that spiritually they were close to death. (The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, Volume 5, Issue 2, Article ID 2344, Feb 2, 2007.)

Lu Xun’s motivation to become a writer was to be able to minister to the ailing Chinese soul. For this he develops a new genre of fiction, actually a new form of communication. Kierkegaard likewise presented his concerns via an elaborate set of literary tropes destined to draw the reader into a web of relationships, forcing the reader, in the process of determining who is speaking and what is being said, to take a stand and thereby discover one’s inward beliefs and commitments. Neither writer tells the reader what to think, but tries to provoke the reader to think.

Neither Kierkegaard nor Lu Xun used literary creations to disguise their identity. Both were prominent in the public space and both, through polemic, irony, and satire, constructed an authorship (to use Kierkegaard’s term) to attack and encourage change in the prevailing social values. In neither case were their literary marionettes independent of their master’s strong authorial intent, but rather presented aspects of their master’s point of view as an author (again using Kierkegaard’s phrase). Both, in quasi-Socratic fashion, interrogate the public, pressing for decisiveness without disclosing—at least not directly or objectively—the purported truth of the matter. Kierkegaard, through one of his pseudonyms (Johannes Climacus), declares an absolute incommensurability between inwardness and outwardness and then, in the face of doubt and the absurd, avers that subjectivity is truth (Concluding Unscientific Postscript To Philosophical Fragments). Do Lu Xun’s characters, in the face of the doubts and absurdities evident in the China of their day, proclaim the same?

Lu Xun’s True Story Of Ah Q, written in December 1921 and recognized as an outstanding example of the new modern literature provoked by the May 4th movement, was first published in serial form in a weekly literary magazine. The narrator opens the story by discussing the difficulties of writing an historically accurate and sociologically correct account of the main character, Ah Q, whose very name was in dispute. Many readers took the story as a thinly-veiled report on an actual contemporary individual.

A few years later a debate developed among Chinese intellectuals, in which the story’s exemplification of Marxist principles, or Lu Xun’s fidelity to them, was questioned, as well as the story’s relevance for the times. At that point the Communist cause was not going well, and many pro-Communist intellectuals were in the throes of ideological and personal crises. The realistic language and social criticism deployed by Lu Xun led to a debate over whether the central character in the story might be a representative of pre-revolutionary China rather than a contemporary person. (See: Gloria Davies, “The Problematic Modernity Of Ah Q,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, Dec., 1991, Vol. 13, pp. 57-76). The question of greatest concern was whether the story helped the path to revolution, and to the redemption of Chinese society from its insidious past. The questions of subjectivity and the inward consciousness of the individual were not part of the debate, but for Lu Xun, I think the two levels of redemption were deeply connected. Indeed, to question the specific historicity of the story may miss its main point.

In the introduction to The True Story Of Ah Q, the narrator reflects on the issues of writing a biography. The question of truth—specifically, how an author could know the truth of another—is put forth as a formidable problem:

For several years now I have been meaning to write the true story of Ah Q. But while wanting to write I was in some trepidation too, which goes to show that I am not one of those who achieve glory by writing; for an immortal pen has always been required to record the deeds of an immortal man, the man becoming known to posterity through the writing and the writing known to posterity through the man—until finally it is not clear who is making whom known. But in the end, as though possessed by some fiend, I always come back to the idea of writing the story of Ah Q. (The True Story of Ah Q. Chapter 1, Introduction)

The narrator then cites the Confucian dictum regarding the rectification of names, to the effect that if you have a name wrong, everything falls into a state of disorder. This leads directly to the problem of authorship. According to the Confucian principle, if a name is correct—say that of a father—the correct role and authority of the person is properly indicated. If you do not know someone’s name, how can you know the authority by which they speak?

This question is confounding, as the narrator of The True Story Of Ah Q makes clear. To tell someone’s true story presupposes knowing their name. The narrator tries to sort this out by imagining what sort of biography could or should be written to keep the story of an individual alive, and to what purpose? Only to keep alive a memory or to offer an edifying example? Both Kierkegaard and Lu seem to favour some version of the latter, Kierkegaard calling for a corrective and Lu Xun wanting to heal the Chinese soul. Not having the correct name questions both the status of the character and the authority of the narrator.

Both Kierkegaard and Lu Xun want to evoke the awakened consciousness that accompanies moral rectitude and psychological happiness, yet neither writer possessed a calm and optimistic outlook regarding their own well-being. In Repetition, his psychological experiment, Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous author Constantin Constantius advises a (nameless) young man whose melancholic state resembles that of the puppet master. But the advice is neither straightforward nor likely to be effective. Howard Hong, Kierkegaard’s editor and translator, summarizes the situation in this way:

Repetition is a small work, but in it repetition is defined and illustrated in numerous ways. For the author it means the recurrence of an experience. For the Young Man it means the recovery of his split self after the experienced breach caused by the ethical dilemma of his breaking an engagement. They both fail and become parodies of repetition. Constantin despairs of esthetic repetition because of the accidental, contingent aspects of life, and ends in a life of monotonous routine. The Young Man, despairing of personal repetition because of guilt, obtains esthetic repetition through the accidental intervention of his former fiancée’s marriage and is transported into the poet’s world of imagination. Constantin Constantius also points to an-other conception of repetition: “If he had had a deeper religious background, he would not have become a poet.” Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Anxiety, picks out from Repetition three lines that are left undeveloped in the earlier work: “Recollection is the ethnical (ethniske) view of life, repetition the modern; repetition is the interest (Interesse) of metaphysics and also the interest upon which metaphysics comes to grief; repetition is the watchword (Løsnet) in every ethical view; repetition is conditio sine qua non for every issue of dogmatics”—and adds: “eternity is the true repetition”; “repetition begins in faith.” (“Repetition,” The Essential Kierkegaard, p. 102).

Let us focus first on aesthetic repetition as, for the Young Man, this seems to assuage his feelings of guilt and at the same time transport him into the world of poetic imagination. How does aesthetic repetition figure in The True Story Of Ah Q? Ah Q is a victim of recollection. He struggles to recall the right way to be, but as a poor and uneducated peasant, he cannot remember anything that could establish him as a member of the privileged class. He tries to use his inability to remember—that is, his ability to forget—to benefit himself. His displacement from society is in part due to his self-deception, which is in turn due to his faulty or false efforts to remember. Ah Q deludes himself about himself.

Both the Young Man and Kierkegaard himself broke off an engagement to marry out of consideration for their own character transposed into an alleged consideration for the other. Kierkegaard asserted that his melancholy would be a burden too great for Regina to bear. Their engagement was preceded by intense romantic love, creating a prospect for happiness. But as soon as they were engaged, Kierkegaard regretted it and broke off the engagement, creating the ethical dilemma. The circumstances in the case of Ah Q are quite different. Romantic love played no part, but Ah Q’s crude overture to the maidservant to “Sleep with me!” was an unreflective response to the curse, “May you die childless,” that he received from a nun in the Tutelary God’s Temple. The overture reflected neither honest self-understanding nor any thought for the well-being of the maidservant. It was a thoughtless and unreflective attempt to attain gratification and social standing. In this way, Lu Xun is critical of the underdeveloped consciousness of his fellow Chinese.

The controversy over Lu Xun’s attitude toward the revolution, and Marxist and Communist principles in general, is beyond the scope of this discussion, except for one aspect—his use of satire, which became a key issue in the reception of his literary works. Lu Xun, like Kierkegaard, was a public figure, and acrimonious debates and accounts of his activities sometimes appeared in the press. In the bourgeois Denmark of Kierkegaard’s time, his attitudes were occasionally seen as scandalous. Like Lu Xun, Kierkegaard is revered today—he is mentioned alongside Hans Christian Anderson, Carl Nielsen, and Niels Bohr—but during his lifetime he was criticized and even ridiculed. A satirical weekly newspaper, The Corsair, published nasty caricatures of him and mocked his writing and pseudonymous disguises. Kierkegaard sometimes attacked other writers, including his contemporary, Hans Christian Andersen, whose early novels Kierkegaard eviscerated in his 1838 publication, From The Papers Of One Still Living.

In Lu Xun’s case, the official Chinese position has mostly been to glorify his status. In his eulogy, Mao said:

On the cultural front, he was the bravest and most correct, the firmest, the most loyal, and the most ardent national hero, a hero without parallel in our history. (“On New Democracy,” in Selected Works Of Mao Zedong, Vol. II, p. 372.)

But about his literary style, Mao expressed certain reservations. In the Yanan Forum on Literature and Art, referring specifically to Lu Xun, Mao said:

We are not opposed to satire in general… what we must abolish is the abuse of satire. (“Yanan Forum on Literature and Art,” in Selected Works Of Mao Zedong, Vol. III, p. 92.)

When part of indirect communication, satire and the other forms of the comic, humour and irony, shift responsibility from the author. Although Mao no doubt criticized at least some of Lu Xun’s satiric characterizations, it was possible, given the shift implicated by the indirect method, to see the spirit of revolution maintained in the works.

The use of experimental literary values and styles, the predilection to indirect communication, and the use of humour, irony, and satire are seen in the writing of both Lu Xun and Kierkegaard. Influenced by the May 4th movement, Lu Xun had a strong interest in and appreciation for modern Western literature, and it is reflected in his style. He was also familiar with the works of Kierkegaard. While not embracing Western metaphysics or religious doctrines, his writing exhibits an interpretation of the human condition that is neither derivative of the predominant Chinese traditions nor strictly adherent to Marxist or Communist ideology. Despite their misguided outlooks, his characters, Ah Q and the Madman, are portrayed as individuals whose existential anxiety puts them in company with Kierkegaard’s individuals.

The anxiety portrayed by Lu Xun at first seems to be quite different from that diagnosed by Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard’s treatise on anxiety, The Concept Of Anxiety and subtitled A Simple Psychological Orienting Deliberation On The Dogmatic Issue Of Hereditary Sin, addresses a problem within Christian theology that is not an issue for Lu Xun. Still, the book makes statements about the psychology of anxiety that reflect Lu Xun’s outlook:

Innocence is ignorance. In innocence, man is not qualified as spirit but is psychically qualified in immediate unity with his natural condition.… In this state there is peace and repose, but there is simultaneously something else that is not contention and strife, for there is indeed nothing against which to strive. What, then, is it? Nothing. But what effect does nothing have? It begets anxiety. This is the profound secret of innocence, that it is at the same time anxiety. Dreamily the spirit projects its own actuality, but this actuality is nothing, and innocence always sees this nothing outside itself. Anxiety is a qualification of the dreaming spirit. (“The Concept Of Anxiety,” in The Essential Kierkegaard, p. 139.)

There is an important difference between the actual circumstances that threaten our material lives—which must be acknowledged and resisted—and psychological anxiety. Anxiety, Kierkegaard says, is something different—it is awareness of the absence of being, that is, of nothing. Anxiety is fear of nothingness. In this state, one does not act. Thus, the apprehension Lu Xun had about the Chinese non-reaction to the execution of their countrymen, in contrast to the spirited response of the Japanese, was his recognition of this dreaming, escapist spirit. The response of Lu Xun would be The Call To Arms.

A lesser-known work of Kierkegaard, published under his own name (his work as an author having been completed) is Two Ages—The Age Of Revolution And The Present Age: A Literary Review. Ostensibly a review of Thomasine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd’s Two Ages, considered to be the first modern Danish novel of significance, Kierkegaard compares his society with that in an age of revolution. An age of revolution, he says, is “essentially passionate; therefore it has not nullified the principle of contradiction and can become either good or evil, and whichever way is chosen, the impetus of passion is such that the trace of an action marking its progress or its taking a wrong direction must be perceptible. It is obliged to make a decision, but this again is the saving factor, for decision is the little magic word that existence respects.” (“Two Ages,” in The Essential Kierkegaard, p. 265.)

This is not far from Lu Xun’s notion of revolution. The point that Kierkegaard emphasizes, that an age of revolution demands decisiveness, explains the criticism of Ah Q. But does revolution answer to anxiety, or is the answer to our anxiety a call to arms? Or perhaps, is our age not one characterized primarily by anxiety, our collective consciousness that of a dispirited psychology in the face of nothingness?

It seems undeniable that we are living in an age of anxiety, of dispiritedness manifest as a growing sense of hopelessness. Many perceive our hopelessness as the absence of decisiveness regarding global phenomena that ultimately threaten our very survival. Whether it is COVID-19, global warming, the prospect of a society in which robots replace all forms of human labour, or the growing nationalist isolationism setting people against people, one asks: what would it mean to be decisive, and how would it be possible? The feeling of helplessness in the face of such potential calamities first leads to anxiousness, then possibly to feelings of depression, and eventually to the sort of dream state in which the self disengages from itself.

What sort of personality can face such hopelessness? The guests invited to Kant’s dinner party certainly were not beset by this. Would the guests at our imagined dinner party, the pseudonymous speakers sent by Lu Xun and Kierkegaard, do any better? Kierkegaard ultimately subordinates all worldly concerns to the redemption promised by religious salvation. His trenchant analysis of the human spirit does not overcome the problems of material decline. The sickness unto death, the despair over our own mortality, stems from the inability to die, which is caused by a misrelation of the self to itself in terms of the divine promise. The inward mis-relationships in Lu Xun’s characters, on the other hand, have removed them from the world, and it is only in the world where redemption can be sought.

Despite a similar diagnosis, the path to hope seen by these two authors goes toward different destinations. What they have in common is the need for decisive commitment, even in the face of the absurd.

Professor Emeritus at NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Teacher and administrator in higher education for over 40 years, serving on the faculty of a liberal arts college and a school of engineering. With an educational background in the history of philosophy, he has had a lifelong interest in science and technology. His current research and writing interests focus on the philosophy of technology, global philosophy and technological ethics.

Nadou Fredj is a Franco-Tunisian artist, trained at the Marseille School of Fine Arts, she mainly focuses her creations on the theme of food and childhood.She combines realism and enchantment, through the diversion of everyday objects, finding its essence in an iconography strongly linked to children’s stories. Nadou Fredj questions the themes of identities by invoking memories, intimacy, culture and the relationship to the body.

Professor Emeritus at NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Teacher and administrator in higher education for over 40 years, serving on the faculty of a liberal arts college and a school of engineering. With an educational background in the history of philosophy, he has had a lifelong interest in science and technology. His current research and writing interests focus on the philosophy of technology, global philosophy and technological ethics.

Nadou Fredj is a Franco-Tunisian artist, trained at the Marseille School of Fine Arts, she mainly focuses her creations on the theme of food and childhood.She combines realism and enchantment, through the diversion of everyday objects, finding its essence in an iconography strongly linked to children’s stories. Nadou Fredj questions the themes of identities by invoking memories, intimacy, culture and the relationship to the body.