Medicine, Ethics and Artistic Representation in Late Imperial China

China is not the only society interested in procreation, but due to its long-entrenched practice of ancestor worship, it is obsessed with domestic reproduction. In this essay, I will discuss the medical knowledge that facilitates this tradition, the Confucian ethics that underwrite it, and the artistic works that represented this everyday concern during the late Imperial period (12-18th centuries), which represent a case par excellence for the hopes that ordinary people have and the anxieties such wishes may create in pursuing their uncertain fulfilment.

Reproductive Medicine

Traditional Chinese pediatrics (youke), gynecology (fuke) and, later, male medicine (nanke) all aimed at successful reproduction and the raising of children. Published research discusses the first two in detail,1 so I will focus on the third concern, which has hardly been studied.

Compared to Europe, where pediatrics emerged in the early modern era, traditional Chinese pediatrics had surfaced by the 12th century, in the Southern Song Dynasty, with identifiable physicians, texts, and clinical records, under the strong influence of society’s need for breeding and bio-physical upbringing. From early in the latter half of the first millennium of the Sui-Tang era, chapters on newborn care appeared in medical texts. By the time of Qian Yi’s career as the founding father of Chinese pediatrics, medical discourses, pharmaceutical prescriptions, and clinical case records make it evident that Chinese pediatrics operated in an increasingly mature form.2 There is little question that Confucian beliefs in ancestor worship and family ethics formed the social soil that nurtured this specialist knowledge, and that continued to support its growth.

Traditional Chinese gynecology and obstetrics reveal a similar intellectual and professional development. Scholars in the history of women’s medicine3 and anthropology4 have published extensively on the ways in which gynecological concerns worked toward the enhancement of women’s health, with successful reproduction in mind. Traditionally, domestic space had been designed to nurture geneaological activities and to extend genealogy, socially and bio-physically. Ritual arrangements had been made to create socio-cultural surrogates, including social mothering (cimu), adoption within the clan (guoji), and ancestry sharing (jiantiao), to carry on the flickering of the ancestral fire (xianghuo). Also, polygamous marriage had ostensibly been adopted, under the need for the generating of male offspring.

In terms of medical knowledge and skills in its service, the appearance of male medicine (nanke) texts represented an outstanding development. Although male medicine emerged later than medicine for women and children, medical texts and practitioners devoted to helping men enhance their chances for bio-physical reproduction deserve special attention.

Based upon the core texts of male medicine available until now, the period when nanke appears to have flourished as a clinical practice was the middle of the 16th century through the end of the 17th. Accumulated medical understanding and skill had met the increasing demand from landed gentry/scholar families in China’s lower Yangtze valley region to bring forth a specific medical subspecialty. It should also be mentioned that the development of commercial print culture during this same period, and in the same region, helped to produce the cultural products needed for the circulation of this specialized knowledge, also leaving behind a paper trail showing the vitality of the social forces at work at the time.

Content analyis of these seven core texts reveals two types of authorship. The first are those produced by medical doctors or scholars with medical backgrounds. Important Principles For The Increase Of Offspring by Wan Quan (1499-1582) and Proposals For Successful Breading by Zhang Jiebin (1563-1642), belong to this category. Then there are texts like Genuine Insights Praying For The Birthing of Offsprings by the popular writer Yuan Huang (1533-1606), which appeared as a successful adaptation of current specialist knowledge in reproductive medicine in order to meet consumers’ needs on the subject. In the midst of a surge in the reading public’s appetite for such literature, a lively commercial print culture put together cultural products that borrowed celebrity names, and any combination of random notes from practising physicians, mixed by editorial hands in the repackaging of quasi-specialist information. The famed text Medicine For Men by Fu Qingzu (1606-1680) is a clear example. Largely, however, booklets by middle-ranking medical authors, bringing forth mundane advice, seems to have carried the day. Correct Medical Treatise On Planting The Seeds From The Miao Yi Studio by Yue Fujia, in two volumes that appeared in the market in 1636, or Yu Qiao’s Important Words For Increasing The Offspring are good examples.

The most significant conclusion after investigating the content of this wave of popular advice, is that the burden of the duty of procreation was finally and squarely laid on the shoulders, the bodies, and the souls of men. As the potential father-to-be, it was his responsibility to prepare for hopeful breeding. These preparations included religious, ethical, and philosophical self-cultivation, and physical bathing and self-cleansing, days, months, and years before pharmaceutical prescriptions and physical maneuvring could be called upon to facilitate procreation. The pressure was on the man, no longer his female partner.

The Ethical Price Of Procreation

Nothing revealed the need to procreate more succinctly than to see male medicine, its authors, practitioners, and customers—all men from later imperial China—willingly assign the duty of procreation to the body of the male protagonist. In Confucian ethics as well as everyday existence, this was a huge concession in gender relations and an enormous price to pay in personal life management.

In the intellectual and social history that lead to this cultural self-fashioning, we see a male-centered, carnal-pleasure-seeking trend from medieval China yielding to the Daoist re-emphasis on self-preservation and longevity (shesheng) after the Sui-Tang era. This prepared the stage for the valuing of bio-physical procreation and socio-cultural reproduction in the second millennium of the Chinese Empire after the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The value of a man in the lifestream of his clan now rested in his position as an adult son, and married husband, in need of an heir.

Song-Ming Neo-Confucian ethics saw the philosophical truth in the realms of bio-physical and socio-cultural reproduction all rolled into one.5 An enchantment with the element of emotion in societal interplay since the mid-Ming dynasty provided the later imperial era with a more conducive environment for gender-balanced positioning, opening to reciprocal social exchanges and sexual conduct. Scholarly work on companionate marriages among the educated elites in Jiangnan (lower Yangtze valley) during the 16th to 18th centuries attests to a social air friendlier and more constructive to negotiable woman/man relations.6 Male partners and husbands cultivating the right conditions, waiting in chamber activities, watchful for the gentle moment for his female partners “to come” became less unthinkable by the 16th century.

Still, to add for oneself the main duties in bio-physical reproduction is not a light task, in that it sharpens the focus of collective hope, and the commensurate anxiety therein, to carry on the family line. It was a bigger burden, comparatively speaking, because the goal was not to simply produce any child, even any boy. The agreed-upon aim was for a good man to produce a boy that will have a long life, and will also turn out to be an intelligent degree holder and filial offspring, all depending upon the ethical and religious body that generated the moment of procreation.

Such moments would begin long before, with the lifelong pursuit of self-cultivation and personal virtue, which then led to physical washing and rites of purification. These pursuits also included pre-coital rituals of purposeful separation, the selection of the right days and moments for sexual intercourse, and post-coital watchfulness and medicinal nurturing to enhance the chances of successful breeding.7 If all this appears curiously “modern” for the gender-balanced obligations put on men, historians can see that some of these socio-cultural elements have remained in the subterranean Chinese social soil, to resurface during the tumultuous sexual revolution that was part and parcel of the country’s transformation in the complicated modern era, making it all the way, some would argue, to post-modernity in gender, sexuality, and reproductive culture.

The Embellishment of the Arts

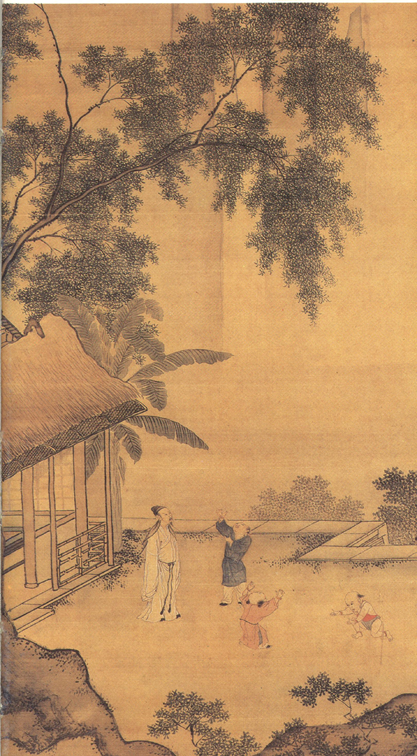

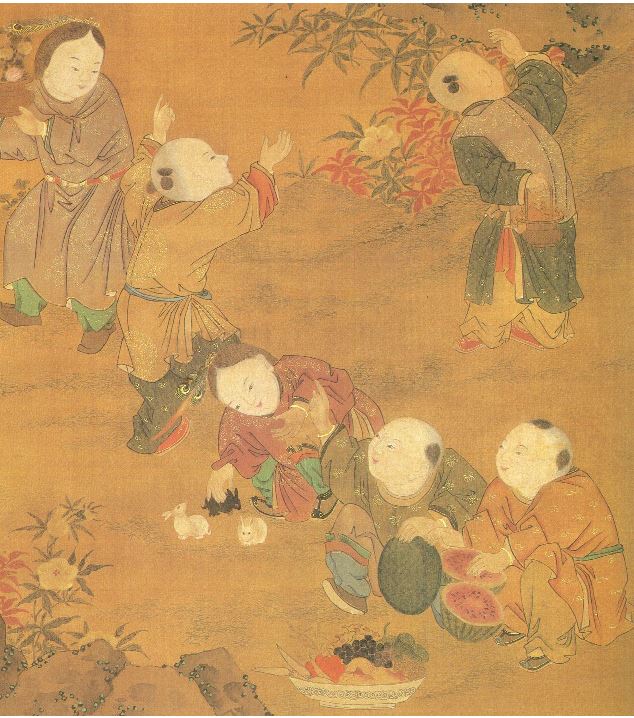

Art in late imperial China was the vehicle for the expression of collective and individual wishes for successful breeding, while medicine took up the duty of providing technical know-how and Neo-Confucian philosophy advised the virtue of practice, during the same period. At the level of art history, the depiction of children at play (yingxi tu) during the Song Dynasty can hardly be over-emphasized, especially posed against Philip Aries’ overstatement that the notion of childhood is a modern invention.8

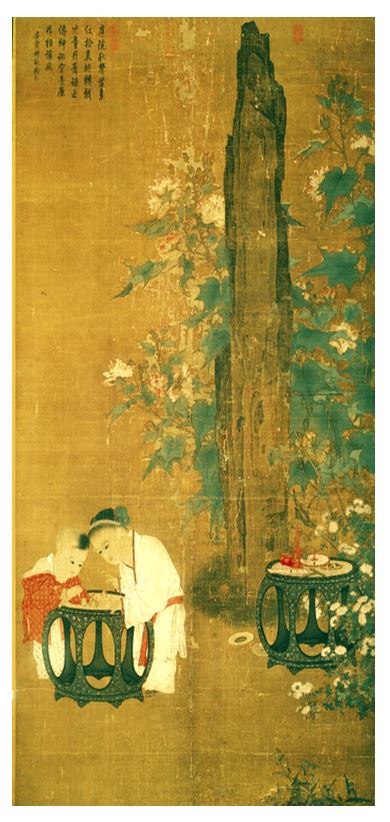

Representations of children at play, at their cultural peak during the Southern Song Dynasty, would depict a girl and a boy playing outdoors during the four seasons of spring, summer, fall, and winter. Although complete sets of all four no longer exist, surviving originals of one or two are still available for viewing, mostly at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. These artistic creations were produced by specialists who did nothing but the paintings of children, from generation to generation. Su Hanchen and his son were the best known of these specialist painters in the school of “fine details” (gongbi). From the fact that such large-sized, high-quality pieces on frail paper have survived nearly a thousand years, it is evident that these are artistic testimonies to the forces that wished and prayed for the happy noises of girls and boys in play.

Considered side by side with the social forces eager to enhance the possibility of birthing, together with the Neo-Confucian teachings emphasizing one’s inescapable duty to pass on the cultural heritage through the family line, it is not difficult to imagine what motivated these artists. Witnessing depictions of girls and boys at play, everyone in the audience would have understood that this signalled happy results—children had not only had been fortunately conceived and happily survived birthing, but their new lives had passed through all of the challenges of nursing, teething, and so on, and can now be seen playing with their mates in the family yard, plump, healthy, and in good cheer, surrounded by pets, toys, fruits, and flowers, free of care and oblivious to worldly worries, far from any ailments and plagues not actually far from them at this time.

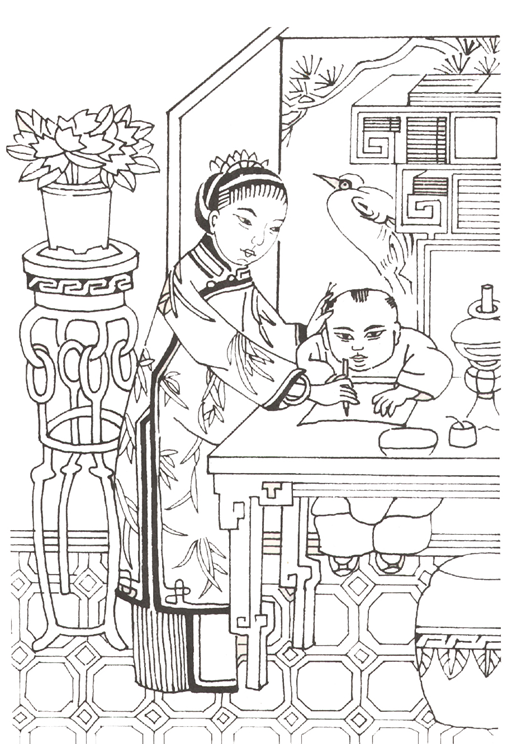

At the high tide of this cultural pursuit, paintings in related genres such as knick-knack peddlers (huolang tu) or “tilling and weaving” (gengzhi) from the Song through the Ming Dynasties show a superbly expert eye for the affairs of infants and children. Depictions of playful children can be seen in other art forms as well, such as wood and bamboo carvings, porcelains, and miniature sculptures. From the Ming Dynasty on, this artistic genre lost its great zest; the few representations that kept the name of the genre no longer exhibited at the same level of artistic charm. By the Qing period, the expression of related interests could be found in the profiling of young lives and youthful activities in festivities (e.g., suizhao huanqing) or holiday fairs (taiping chunshi), in wood carvings like Teaching The Children (jiaozi jiaonu tu) and in popular New Year prints (nianhua). Pro-natal forces carried on.

- Hsiung, A Tender Voyage; Furth, A Flourishing Yin.

- Hsiung, A Tender Voyage.

- Furth, A Flourishing Yin.

- Bray, Technology, Gender And History In Imperial China.

- De Bary, Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy And The Learning Of The Mind-And-Heart.

- Ko, Teachers Of The Inner Chamber; Mann, Precious Records.

- Hsiung, A Tender Voyage.

- Aries, Centuries Of Childhood.

Bibliography

Aries, Phillipe. Centuries Of Childhood: A Social History Of Family Life. Traduction Robert Baldik. New York: Vintage Books, 1965.

Bray, Francesca. Technology, Gender And History In Imperial China: Great Transformations Reconsidered. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2013.

De Bary, William Theodore. Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy And The Learning Of The Mind-And-Heart. Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Furth, Charlotte. A Flourishing Yin: Gender in China’s Medical History: 960–1665. University Of California Press, 1999.

Hsiung, Ping-chen. A Tender Voyage. Stanford University Press, 2005.

Ko, Dorothy. Teachers Of The Inner Chamber: Women and Culture In Seventeenth-Century China. Stanford University Press, 1995.

Mann, Susan. Precious Records: Women in China’s Long Eighteenth Century. Stanford University Press, 1997.

Hsiung Ping-chen is Professor of History and Director of the Taiwan Research Centre at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. She received her Ph.D. in History from Brown University and her S.M. in Population Studies and International Health from Harvard University. Her main research interest lies in the area of women’s and children’s health.

Hsiung Ping-chen is Professor of History and Director of the Taiwan Research Centre at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. She received her Ph.D. in History from Brown University and her S.M. in Population Studies and International Health from Harvard University. Her main research interest lies in the area of women’s and children’s health.