Between daily realities and the instinct to survive, two states of mind now appear to dominate the spirits of people—anxiety and hope.

Creativity is a catalyst between these two mental states, inciting a vital process of constantly identifying, recognizing, realizing, thinking, and questioning while also continually leading toward solutions, projecting into the future with imagination and hope.

Creativity is part of the process of life, in which each aspect contributes to the whole. Creativity is a non-separable functioning of the brain. As the capacity to envision and invent, it is an integral part of all human activity. Art is intrinsic to life and to society. Without inventiveness, people could not move from one situation to another.

Fluxus artist Robert Filliou said, “I am not only interested in art, I am interested in society of which art is only one aspect.” He then proposed that “art is a function of life plus fiction which tends towards zero. If fiction equals zero, then art and life are one and the same thing (speed of art). This element of fiction, that is to say the passage, [is] the minimum point between art and life.”1 From this we can conclude that creativity, and therefore art, are vital to life.

Hope incorporates both cognitive and non-cognitive aspects of the mind. Social psychologist Barbara Fredrickson2 claims that happiness can be measured. In her research on emotions, she argues that hope invites humanity to creativity. Hope, then, is a state of mind based on an intuitive probability of endurance—a will and a desire for an optimistic future. Consequently, hope is not only an attitude but an intuitive, cognitive virtue.

Elpis (Hope) appears in ancient Greek mythology in the story of Prometheus. Prometheus stole fire from Zeus, the supreme god, which infuriated him. In turn, Zeus created a box that contained all manner of harmful spirits. Pandora opened the box, and freed all of the illnesses of mankind—greed, envy, hatred, mistrust, sorrow, anger, revenge, lust. Still inside the box, however, is the healing spirit, Hope.

Anxiety is an unpleasant state, a feeling of worry, nervousness, and unease. Although anxiety is closely related to fear, it can be distinguished from fear which is a cognitive and emotional response to a perceived threat.

Both hope and anxiety, then, are intuitive and inseparable functions of the human condition. Both look to the future, and can benefit a person in solving problems. Hope and anxiety are not only attitudes or cognitive components—they reflect and draw upon our fears and desires.

Internal Chaos

Being aware of the past, present, and future states of one’s life is also being an active and conscious participant in the process of living and decision-making. Internal chaos is a form of anxiety, while hope is a place of convergence.

Vitalism considers thinking a “fold” of the world, an extension of matter, as theorized by Gilles Deleuze, which operates by affirmation and is the antithesis of dialectical thought. In this view, there is no longer any confrontation between consciousness and the world; rather, thought goes back to the “chaos of the being that generated it,” as expressed by Véronique Bergen.3

The philosophy of Clement Rosset is one that endorses reality through joy, without hiding any aspect of it.4 The paradox between joy and the facts of life is that we intuitively strive to hope. The term that Friedrich Nietzsche gave to this state of mind is “tragic.” While he argues that the love of life is tragic, Rosset contrasts tragedy with joyful visions. In his view, the developing of hope within a state of anxiety allows each of us to express a dream—a creative, singular reason for meta-self-enquiries of “why” and “what.”

Hope—A Catalyst of Freedom

All civilizations use the arts and sciences as tools to bridge the gap between the present and the future. Humanity has created the arts, sciences, and philosophy to question fundamental notions of freedom. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said in a Washington D.C. speech in February 1968, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.”5

Existing conceptions of anxiety tend to view it in negative terms and describe hope as naive projection, but anxiety plays an important role in the state of well-being, together with hope, as both are agents of the capacity to rationalize. Clinical psychologist David Barlow claims that humans (and animals) are stimulated to creativity by the experience of anxiety, defining it as “a forward-looking state of mind in which one is ready or willing to attempt to cope with the negative events to come.”6

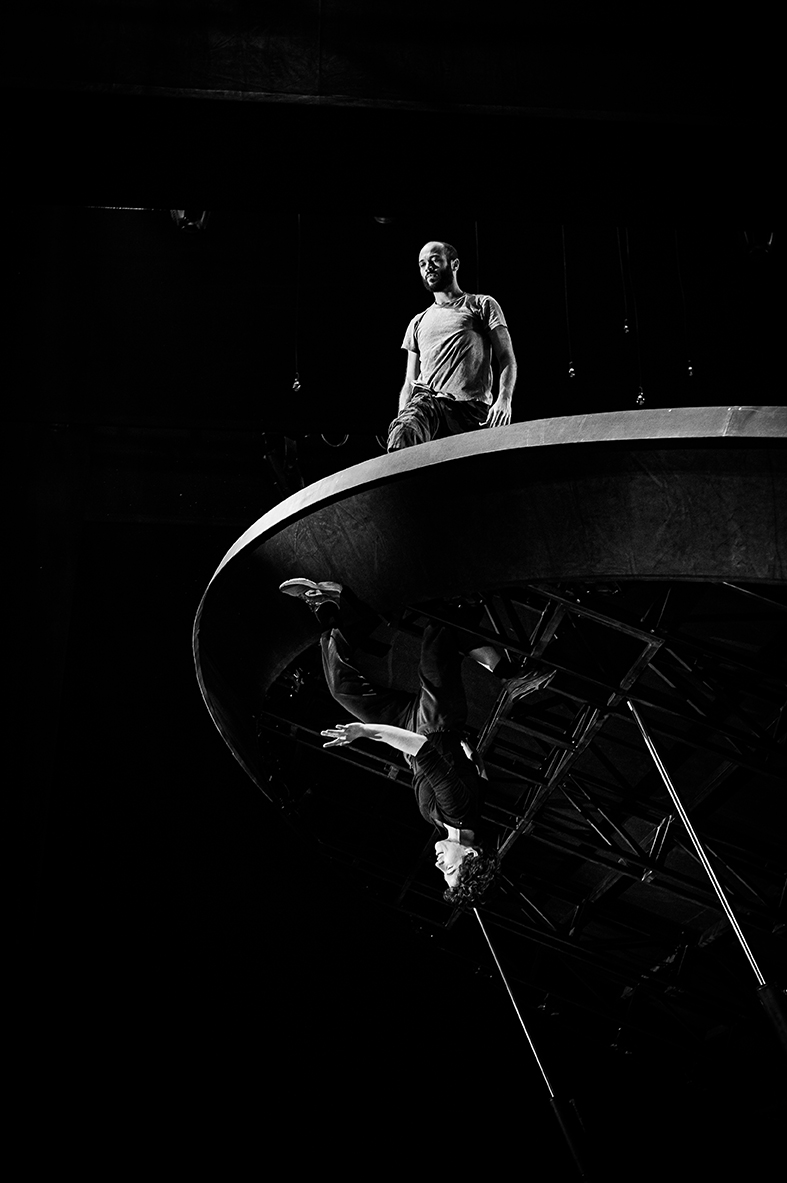

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Western philosophers referred to anxiety as one of the keys to the concept of Existentialism. Søren Kierkegaard offers an analysis of anguish in relation to freedom and sin: Freedom poses questions on limits and responsibilities toward others. Sartre precisely defines “being” as “being-with-others.” In a continuation of Kierkegaard (and Heidegger), he argues that anxiety appears in a man in whom existence precedes essence, i.e., who is responsible and free: “[…] it is first of all a project that is lived subjectively, that is thrown down towards a future.”7 This means that the responsibility of each person in a state of freedom is a source of anguish, which Kierkegaard describes as the vertigo of freedom and a refusal of responsibility for the past.

Commitment and Action

The realities of modern civilization are underlined by the tragic consequences of its own doing—unchecked climate change, unprecedented migration, irreversible loss of the ecosystem—while continuing to create unfair, unstable economies and political systems, bringing to the surface major social and cultural issues. As Luiz Oosterbeck put it, in 2019:

Societies around the globe have been failing to find solutions for environmental, political, economic and social and cultural collapses, facing a let-down in all Sustainable Development models. Humanity is facing a new great anxiety on individual and collective levels, locally and globally, aside to great instability between nations, cultures and individuals.8

As Emil Cioran,9 a Romanian philosopher inspired by Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Kierkegaard says, in his book A Short History of Decomposition, the instinct of hope is a barren state, while “reality is a creation of our excesses, our immoderation and our disruptions. A brake on our palpitations: the course of the world slows down; without our heat, space is ice. Time itself flows only because our desires give birth to this decorative universe that a little lucidity would strip away. A grain of clairvoyance reduces us to our primordial condition: nudity.” By this he means:

– Nudity is the capacity to expose anxieties and to project in imagination, in creativity, and in action.

– Anxiety will stimulate creative solutions; therefore it will also generate hope.

– Fear, however, may create barriers between people, ideas, cultures, and between collectives and nations.

Actions are elements of hope. Opinions and desires are ways to stimulate the mind with projections toward future events. Hopes are different from expectations, but rather reflect the will to look for possible outcomes. Doing this requires affective engagements with others as well as with events.

In his letters to Menoeceus,10 Epicurus suggests that visions are often manipulated by one’s conditions, culture, and localization, and reminds us to pose questions regarding fundamental social conditions, including our individual involvement in the economy and in the protection and care of the earth and of others. Society must examine the causes of disaster and anxiety as well as simple pleasure; even friendship, like all virtues, is intrinsically linked to desire, will, and hope.

In The Myth Of Sisyphus, Albert Camus claims that life is fundamentally lacking in meaning, and is therefore absurd. Nevertheless, humans will forever search for meaning, like Sisyphus, the figure of Greek mythology condemned to forever repeat the same task.11 Camus also sees revolting as action against disrespect of the human condition. In his famous phrase, “I revolt, therefore we exist,” he called the state of anxiety, bringing about revolt, as hope, thus implying the recognition of a common human condition.

Camus poses a crucial question: Is it possible for human beings to act in an ethical manner within absurd realities? His answer is yes. Experience and awareness of the absurd encourage resourcefulness and creativity, which give birth to hope, and to setting limits to one’s actions. For Camus, metaphysical rebellion is “the movement by which man protests against his condition and against the whole of creation.”12 Anxiety and historical rebellion is, for Camus, the way to turn the abstract nature of philosophical reflection into action to change the world. Historical rebellions are the attempts of people to act within dramatic situations to create positive change.

He says: “[…] everyone tries to make his life a work of art. We want love to last and we know that it does not last. […] we should better understand human suffering, if we knew that it was eternal. It appears that great minds are, sometimes, less horrified by suffering than by the fact that does not endure…. suffering has no more meaning than happiness.”13

The Arts as Catharsis14

Recently, when people were singing from their balconies, they shared common experiences, emotions, and anxieties. The initiative to confront these experiences with song is an instance of the arts creating hope. Creativity emerges from anxiety and merges with new ideas. Art plays its role:

– Albert Béguin stated, in the journal Esprit: “Not only do the arts enter as NOT an insignificant element in any description of societies, but they also bring to light that which cannot be grasped by any other means.”

– Henry Miller said, in a 1960 interview: “What good are books if they don’t bring us back to life?”

– A classic reference to hope by Alexander Pope,15 which has entered modern language, is the saying, from his Essay On Man: “Hope springs eternal in the human breast, Man never is, but always to be blest:”

– Emily Dickinson16 wrote: “Hope is the thing with feathers,” and in her vision, hope is transformed into a willful bird that lives within the human soul.

– Chinua Achebe17 reminds us that society is fundamentally composed of a rich pluralism of identities and realities. For Achebe, hope lies in the will of people to remember their past, searching to balance their histories by retracing and “re-storying” so as to reconstruct their individual and collective identities, in the process driving away the hidden anxieties related to the lack of understanding of those identities.

The arts raise awareness and mirror one’s own experiences with others, creating a situation in which hope can be used as a creative device, a motivating force, and a key concept in most mythologies and social organizations.

I will end by quoting Greta Thunberg: “The one thing we need more than hope is action. Once we start to act, hope is everywhere, so instead of looking for hope, look for action. Then, and only then, hope will come.”

- Robert Filiou, “Une galerie dans une casquette,” Intervention (6), p. 41–43.

- Barbara L. Fredrickson, Positivity: Top-Notch Research Reveals the 3-to-1 Ratio That Will Change Your Life. New York: Crown, 2009, and Fredrickson, “Why Choose Hope?” PsychologyToday.

- Quoted in Aurélien Barrau, “Philosopher, c’est resister,” La vie des idées, 28 January, 2010.

- Clement Rosset, La Philosophie tragique, Presses Universitaires de France, 1960, and “Mort de Clément Rosset, philosophe du tragique et de la joie,” Bibliobs, 2018.

- A Testament Of Hope: The Essential Writings And Speeches Of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Melvin Washington, ed., New York: Harper & Row, 1986.

- David Barlow, Anxiety And Its Disorders: The Nature And Treatment Of Anxiety And Panic, 2nd ed., New York: Guilford Press, 2004.

- Jean-Paul Sartre, L’existentialisme est un humanisme, Paris: Editions Nagel, 1954.

- Luiz Oosterbeek, “CIPSH address to the 2019 General Conference of UNESCO.“

- Emil Cioran, Précis de décomposition, Tel Collection (n° 18), Gallimard, 1977 (first published in 1949).

- Epicurus, Lettre à Ménécée, Editions Flammarion, p. 29-30.

- “Albert Camus,” Stanford Encyclopaedia Of Philosophy.

- Patrick Hayden, Camus And The Challenge Of Political Thought: Between Despair And Hope. Palgrave Macmillan UK, p. 50-55.

- Albert Camus, The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt, Vintage, 1992 (first published in 1951).

- Henri-Irenee Marrou, De la Connaissance Historique, Paris : Le Seul, 1954, p. 273.

- Alexander Pope, “An Essay On Man,” in Epistles To A Friend (Epistle II), London: J. Wilford, 1773, p. 1.

- Emily Dickinson, ““Hope” is the thing with feathers,” Poetry Foundation.

- Katie Bacon, “An African Voice,” The Atlantic, août 2000.

Painter with a Master of Fine Arts from New York University and has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows. Since 1984, she has published several essays and a book, and has initiated multidisciplinary arts events and conferences in the USA, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, promoting, via the arts, a better knowledge of cultural diversity and fostering intercultural dialogue. In 2003, she founded Mémoire de l’Avenir. She has collaborated with public and private institutions, including UNESCO, CIPSH, Musée du quai Branly, Centre George Pompidou, the Louvre, Dapper, Musée d’Arts et d’Histoire de Judaism, the Institut du Monde Arabe, and Musée de l’Homme.

Painter with a Master of Fine Arts from New York University and has been exhibited internationally in solo and group shows. Since 1984, she has published several essays and a book, and has initiated multidisciplinary arts events and conferences in the USA, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, promoting, via the arts, a better knowledge of cultural diversity and fostering intercultural dialogue. In 2003, she founded Mémoire de l’Avenir. She has collaborated with public and private institutions, including UNESCO, CIPSH, Musée du quai Branly, Centre George Pompidou, the Louvre, Dapper, Musée d’Arts et d’Histoire de Judaism, the Institut du Monde Arabe, and Musée de l’Homme.