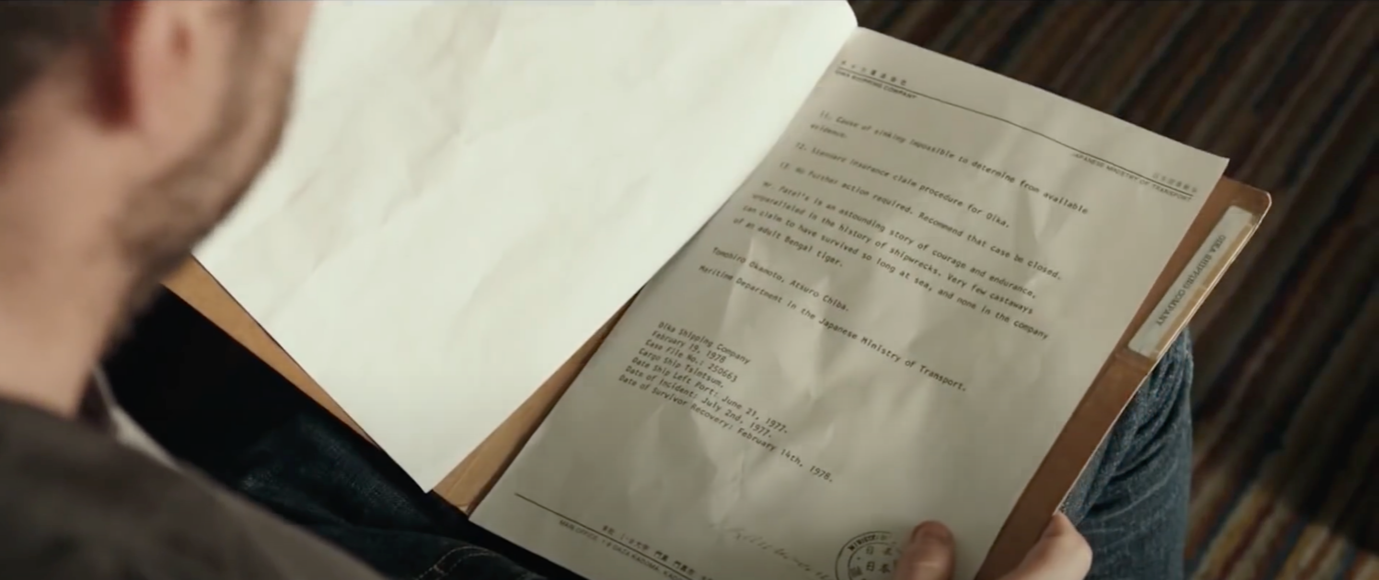

At the end of Ang Lee’s film Life of Pi, there is this episode: When Pi, being interviewed by a reporter, tells him about two insurance company representatives with whom he shared his fantastic story. They did not believe him, and wanted him to tell a more realistic version. (Figure 1) Pi thus tells a different story of his survival at sea. The story is full of killings, cruelty, and hopelessness. It ends with the horrified expressions of the two company representatives, and they choose to believe the first, seemingly beautiful story. Pi then asks the reporter interviewing him, “Which of the two stories do you believe?” “The one with the tiger,” the reporter says. Pi replies: “So you follow God.” Of course, God here refers to the goodness and hope in our hearts.

In 1967, Guy Debord published The Society Of The Spectacle. In the book, he states that “landscape is the materialized view of the world,” and “is a social relationship between people mediated by images.” 1 Debord also points out that the landscape has two important aspects: First, it has become the goal of the current capitalist mode of production and is the “dominant mode of life” for people. The landscape transforms the traditional relationship between material production and consumption into an order in which visual information rules the economy. Second, the landscape has an ideological function, and its existence proves the legitimacy of capitalism. In purchasing the landscape and in unconscious conformity to landscape life, we directly affirm the existing system. The landscape becomes the “permanent presence” of capitalist legitimacy. Today we live with all kinds of advertisements, news, and spam, while uploading all kinds of texts, pictures, and videos. We are not only living in the landscape, but we are also creating a new landscape together, in which we differ only in our ability to create it. Each of us is creating illusions to obscure reality. In such a high-information society, deep desires drive each of us to eventually get lost in the ideological control of the landscape.

The key to the ideological control of the landscape is the medium. Media means discourse, and whoever controls the media in a landscape society controls discourse. The struggle for political power and capital has also led to a further refinement of the division of labour and of disciplines. Given this increasingly refined management, the use, control, manipulation, and guidance of the media make it difficult to distinguish true from false information. As Karl Popper worried in his classic work on political science, The Open Society And Its Enemies, what information is credible in a landscape society constructed by one social engineer after another?2

In today’s post-landscape world, technology has brought more spectacles, and the dense docking of the online carnival created by the masses has long since completely obscured the real world. Whether it is Tik Tok, Kwai, Blibili or Weibo, most information production and dissemination is purposeful. It either creates the landscape or influences the shape of the landscape.3 Debord points out that landscape domination prioritizes the transformation of history to achieve the transformation of personal and community memory and the understanding of memory. The landscape “isolates all displays from its context, its past, its intentions and its results. It is illogical. Because nothing contradicts it, it has the right to contradict itself and revise its past.”4 The landscape, through the socially engineered opinion-monitoring arm it has assembled, can immediately obscure or distort what is happening. Therefore, the search for truth in the landscape society becomes more and more difficult. Does objective “truth” still exist?

History is always in flux, and under the landscape of the dominant ideology of the nation-state, we are constantly digging, regulating, and replacing information to reconstruct our individual and collective memories, and we compile historical information with a critical perspective in order to construct the rationality of the present. In the visual deception created by mass communication, real forms and information have long been lost. Therefore, the question of who is to interpret and how to reconstruct becomes the core of the problem. The internet seems to have opened a gap in the impenetrable landscape, but how much possibility can people domesticated by the landscape create for the new landscape? Does pluralism still work for individuals under the recommendation algorithm? Can the discernment and free time of most people sustain the cost of the pursuit of authenticity? In whose hands is the vetting mechanism of internet platforms?

The alienation and objectification of human beings in the landscape society that Debord criticized has become the norm in this world, and the dissipation of the Situationist International further indicates that this is the direction of human society. But under such a trend, how to resist the disinformation created by the instrumental rationality of modernity? In such an information-based society, how can the information generated by individuals transcend what Arendt called “the evil of mediocrity”?

On the Chinese internet, the idyllic landscape of the Chinese countryside shaped by Li Ziqi in her short videos constitutes a huge contrast with the decaying and withering reality of the real countryside;5 the aimless future mixed with the uncomfortable anxiety of the rural killjoys morphs into a peculiar play and gesture.6 Whether in the online world, controlled by algorithmic pushing, or in the dichotomous world of China’s urban-rural dichotomy, real human connections and relationships become distorted and illusory.

Hannah Arendt suggests that it is a sin to refuse to think. But what happens when we take the pursuit of truth as a faith and finally see through the landscape of false and deceptive information, as we voluntarily swallow the red pill of The Matrix (Figure 2)? How do we face that real world? Dostoevsky already explored this subject in 1880, in The Brothers Karamazov, in three chapters—”Rebellion,”, “The Religious Chancellor,” and “The Russian Friar.”7 Ultimately, all that matters is each person’s own faith, when it contains the need for man to live in truth, the belief in the goodness of human nature, and a belief in a bright future. Within the willingness to pay the price for one’s beliefs lies the reason for a virtuous society.

Sixty-two years ago, the 87-year-old British philosopher Bertrand Russell was asked, in an interview with John Feldman on the British Face To Face program, what life lessons can you share with future generations? Russell replied: ““I should like to say two things, one intellectual and one moral. The intellectual thing I should want to say to them is this: When you are studying any matter or considering any philosophy, ask yourself only: What are the facts and what is the truth the facts bear out. Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish be believe, or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed. But look only, and solely at what are the facts. That is the intellectual thing that I should wish to say.”8

In the post-landscape era, it is often difficult to distinguish between appearances and real information. When lies are packaged by powerful rhetoric, so-called objective and real information is nowhere to be found, and in the decentralized and pluralistic public opinion field, everyone chooses the so-called “truth” discourse with a specific position. Even though the landscape has invaded our lives, we should still hold on to our faith, and human beings need to stand firm upon the ground they actually touch. This is perhaps in line with the salvation of Pi in Life of Pi, that is, the process of human society becoming more mature. Of course, I sincerely hope that our society will be the same as it was after Pi was rescued.

The tiger eventually left and didn’t look back. (Figure 3)

Notes

1Guy Debord, La Société du Spectacle, Buchet-Castel,1967.

2Karl Popper, The Open Society And Its Enemies, Routledge, 1945.

3Tiktok, social networking software launched in China on September 20, 2016, allows users to choose songs, shoot short music videos, and post them for sharing. The platform will update users’ favorite videos according to their preferences. Blibili, an online cultural community and video platform for young people in China, known as “B Station” by its users, was listed on NASDAQ on March 28, 2018. Kwai is an online short video community for users to record and share their productions and lives. Weibo, a Chinese online social media that allows users to share and interact with information instantly in the form of texts, images, videos, and other media.

4La Société du Spectacle.

5Li Ziqi (1990-), a Chinese native from Sichuan, is a creator of short videos on ancient food and a Youtube blogger with millions of fans.

6Shamate, from English SMART, is popular on the Internet. It is characterized by the imitating of the costumes of rock bands from Europe, America, and Japan. Most of the actors are urban immigrants from the countryside after the 1990s.

7Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, published as a serial in The Russian Messenger, 1879-1880.

8 In 1959,John Freeman’s guest on Face to Face. He said: “The moral thing I should wish to say to them, is very simple. I should say: Love is wise, hatred is foolish in this world which is getting more and more closely interconnected. We have to learn to tolerate each other, we have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like. We can only live together in that way. And if we are to live together and not die together. We must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance which is absolutely vital.”

Born in 1970 in Chengdu, China, holds a master’s degree. He is currently a professor and vice president of the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, and vice president of the Chinese Sculpture Society, dedicated to the creation and theoretical research of public art and contemporary sculpture. He has exhibited his personal works in China Art Seasons, Beijing, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong, Canvas Inernatioal Art,Netherlands, Museum of East Asia, Bath, Britain, MOCA Taipei and Shanghai OCT Art Center. In 2012, he initiated the “Yangdeng Art Cooperative” project in Yangdeng Town, Tongzi County, Guizhou Province, and continues to do so today. Now he lives and works in Chongqing, China.

Born in 1970 in Chengdu, China, holds a master’s degree. He is currently a professor and vice president of the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, and vice president of the Chinese Sculpture Society, dedicated to the creation and theoretical research of public art and contemporary sculpture. He has exhibited his personal works in China Art Seasons, Beijing, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong, Canvas Inernatioal Art,Netherlands, Museum of East Asia, Bath, Britain, MOCA Taipei and Shanghai OCT Art Center. In 2012, he initiated the “Yangdeng Art Cooperative” project in Yangdeng Town, Tongzi County, Guizhou Province, and continues to do so today. Now he lives and works in Chongqing, China.