.

Professor Lai passed away suddenly but peacefully on 22 April 2021. His brief but meaningful collaboration with HAS was one of his first attempts to share his thoughts with a non-specialist audience. Professor Lai’s immense legacy will live on in his students and his publications.

This issue of Humanities, Arts and Society focusing on the themes of truth and belief is an excellent occasion to introduce the general public to the operationalization of the everyday life perspective in the study of China’s past. Unlike other historical works that concentrate heavily on important historical figures, a focus on the everyday life of ordinary people allows writers to uncover historical truths on how men and women without political power reacted to epoch-defining transformations. Average Chinese were never passive recipients of ideologies and values propagated by the powerful, as they often formulated belief systems that were the foundations of resistance efforts at an everyday level that defended their collective welfare.

Everyday Life and the Study of China’s Past

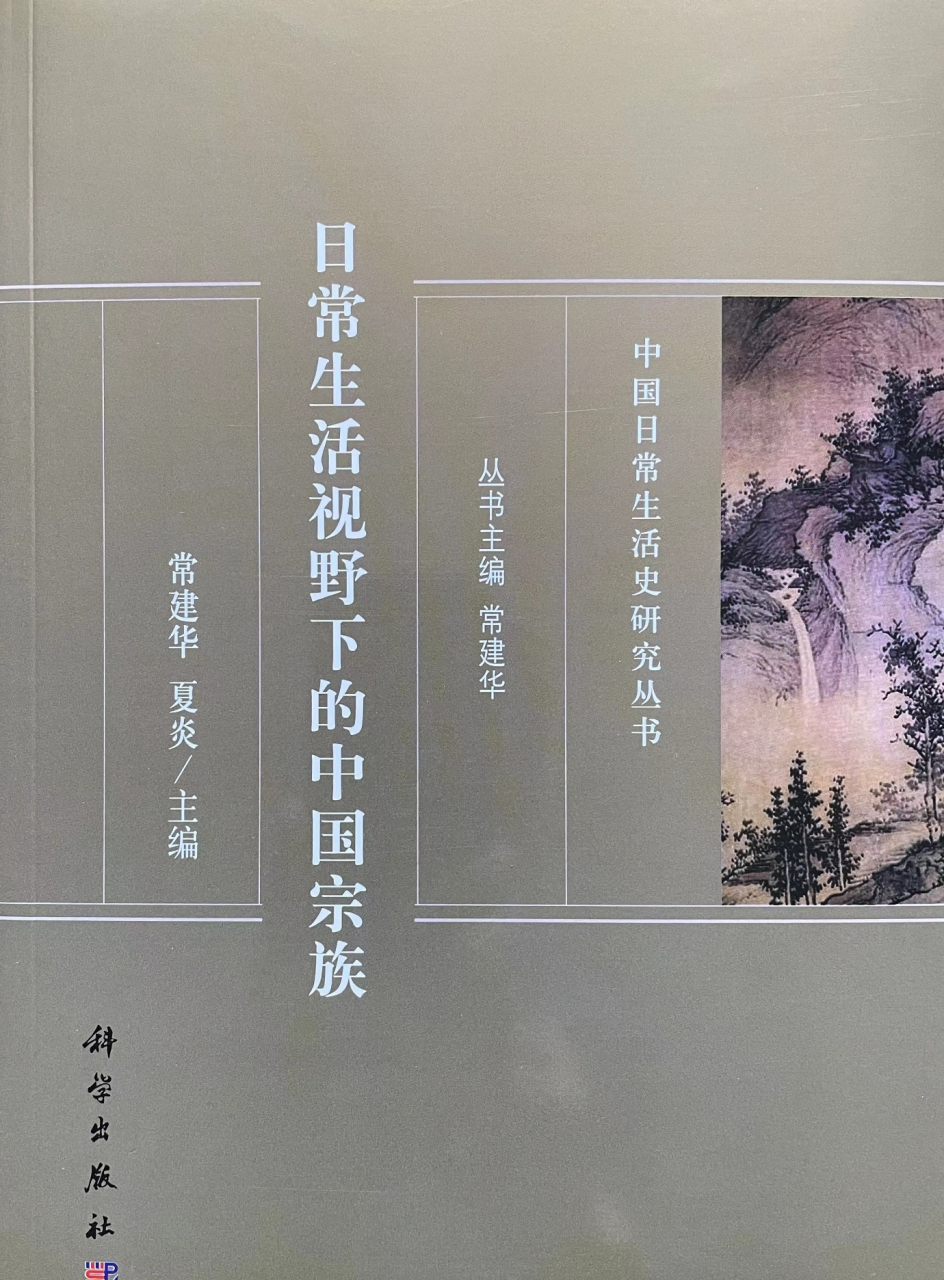

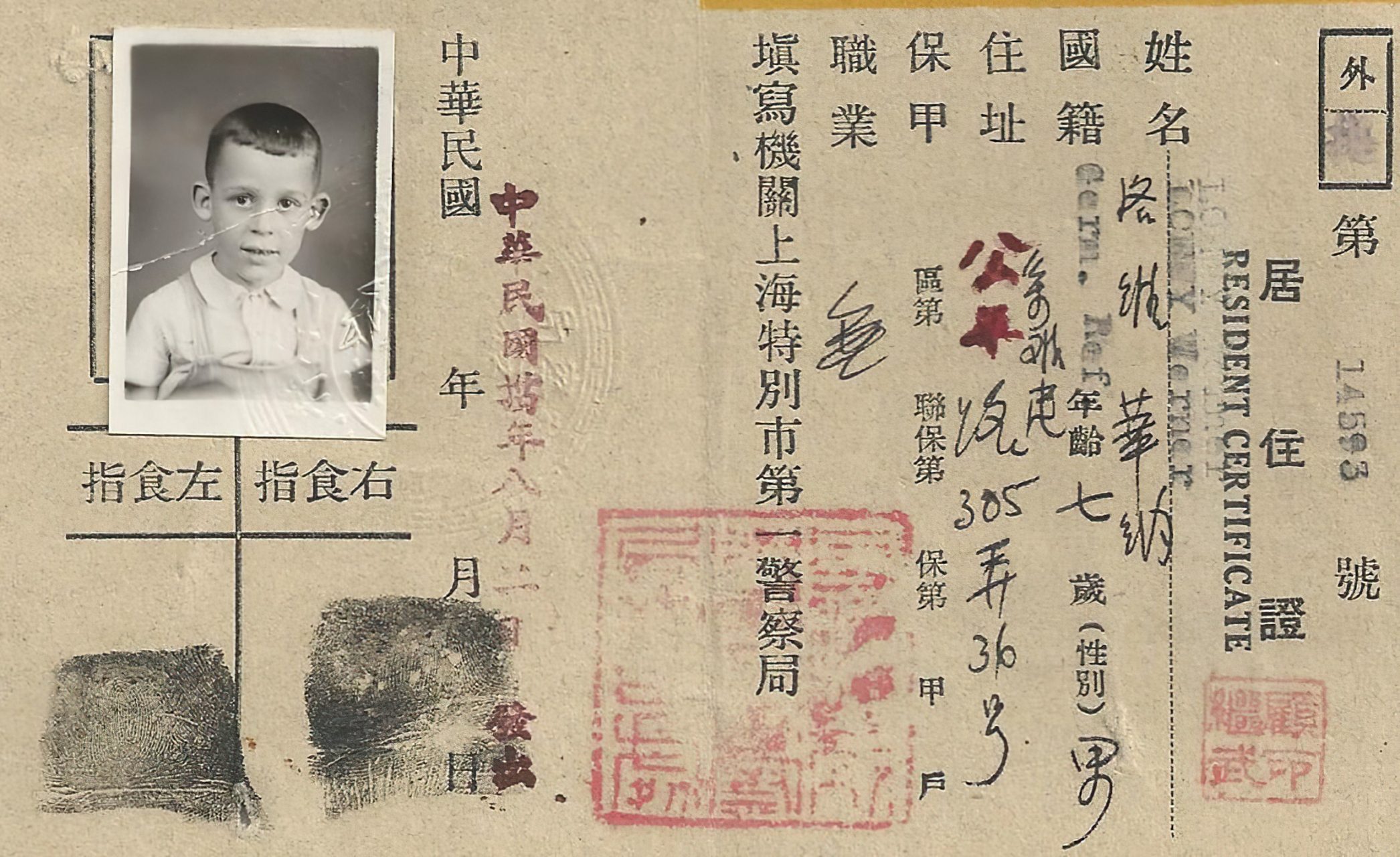

Chinese historians are now increasingly interested in the study of everyday life, which could be defined as feelings, behavioural choices, and opinions a person possessed in daily interactions with other members of society. Accordingly, men and women who did not possess political power have gradually become the focal points of scholarly investigations. Wang Jian’s study of Jewish lives in Shanghai, Chen Zuen’s analysis of the Japanese migrants’ daily existences in the Shanghai International Settlement, and Wang Zhicheng’s examination of Russian nationals in the city have all enriched our understanding of how those who were left out of China’s national narratives and their capacity to not only survive, but thrive in even difficult urban settings.1 Those on the margins of Chinese society have also received the scholarly attention of Di Wang, who relies upon teahouses in Chengdu as case studies to examine how the emergence of consumer culture in China threatened local small businesses and the tenacity of local culture to survive even when state authorities were hell-bent on its destruction.2 The routine acts of everyday life in China has been the focus of Hanchao Lu, who, in his classic article on the “insignificant” daily activities of common people, analyses how the Chinese viewed their relationship with their rulers and China’s external relations with foreign powers who had allegedly mistreated China in the past.3 Chang Jianhua and Xia Ya have served as editors of two magisterial edited volumes, one an analysis of kinship and linage as they were practised by ordinary people in various periods of China’s imperial past, another a survey of everyday life practices from before the Qin dynasty to the Republican era.4

Shift in Emphasis in the Utilization of Everyday Life Perspective in China Studies

The above works seek to chronicle, explain, and analyse how everyday life in various periods of China’s past came to be and are not interested in the ways in which ordinary men and women challenged the existing power structures. An advancement in the utilization of the everyday life perspective, however, requires an analytical framework that could shed light upon ordinary people who possessed the means to resist ideologies or systems of power that were designed to subjugate them. Ordinary people were, if not exactly powerful, then at least possessed the capacity to influence past events. Although it is of course important to study the “shaping power[s] of super-individual force,” a historian’s overemphasis on great historical changes or events could result in him or her ignoring those who were on the front line of epochal transformations and rendering the powerless voiceless also, in spite of the fact that records of their struggles, aspirations, and defeats are available for scholars to discover.5 There is a need to examine “history from below” as advocated by historians such as E.P. Thompson.6

It is incumbent upon historians to ask themselves what everyday life felt like for ordinary people so that analysts could come to a better understanding concerning the immense emotional costs of social transformation that were born by average men and women.7 Since “objects do embody and reflect cultural belief,” investigations into how an object was created, consumed, and utilized by men and women of the past would enable an analyst to “extract information” from a particular epoch.8 Indeed, the process by which a piece of clothing came into the possession of a person reveals his or her income level and receptiveness to various advertising campaigns or different trends in popular culture.9 “The making, the distribution, and the use of” of consumer products therefore contain insights concerning elite intentions and the capacity of average men and women to subvert these intentions.10

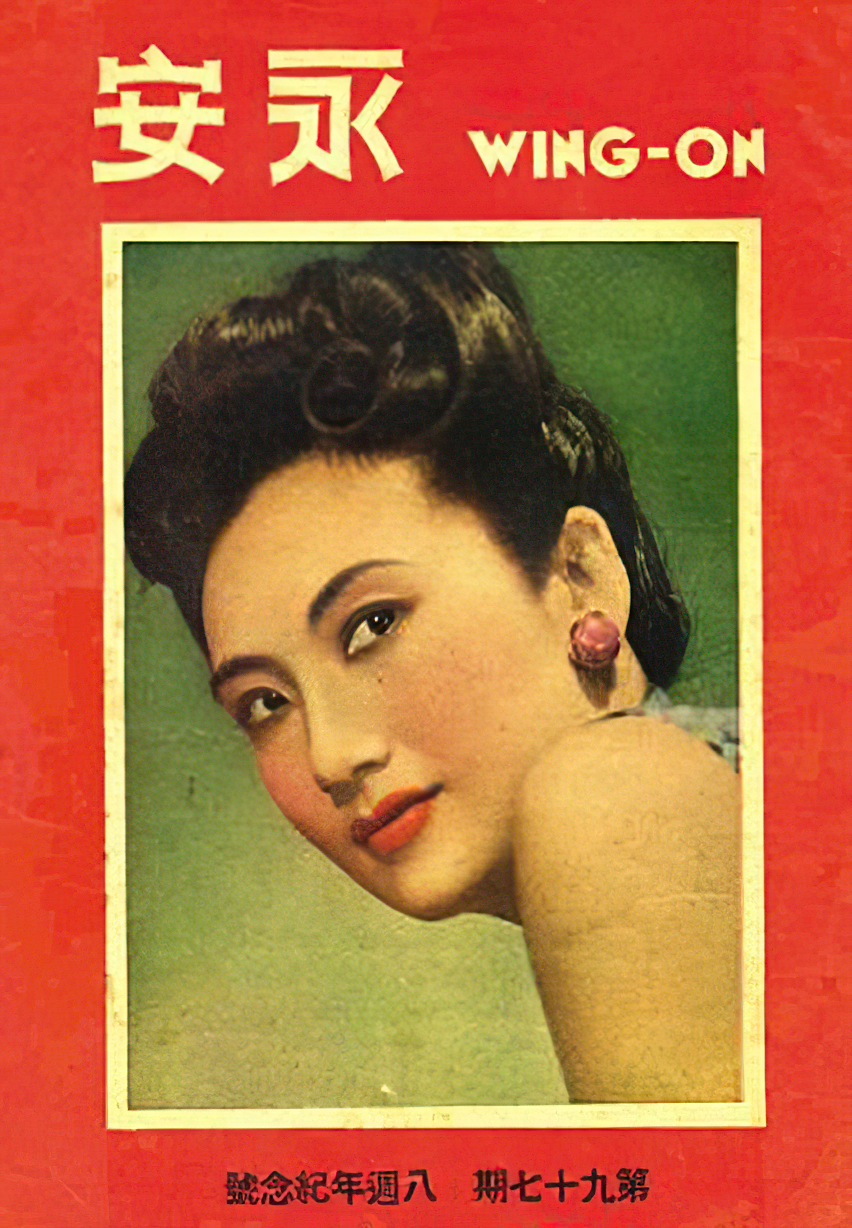

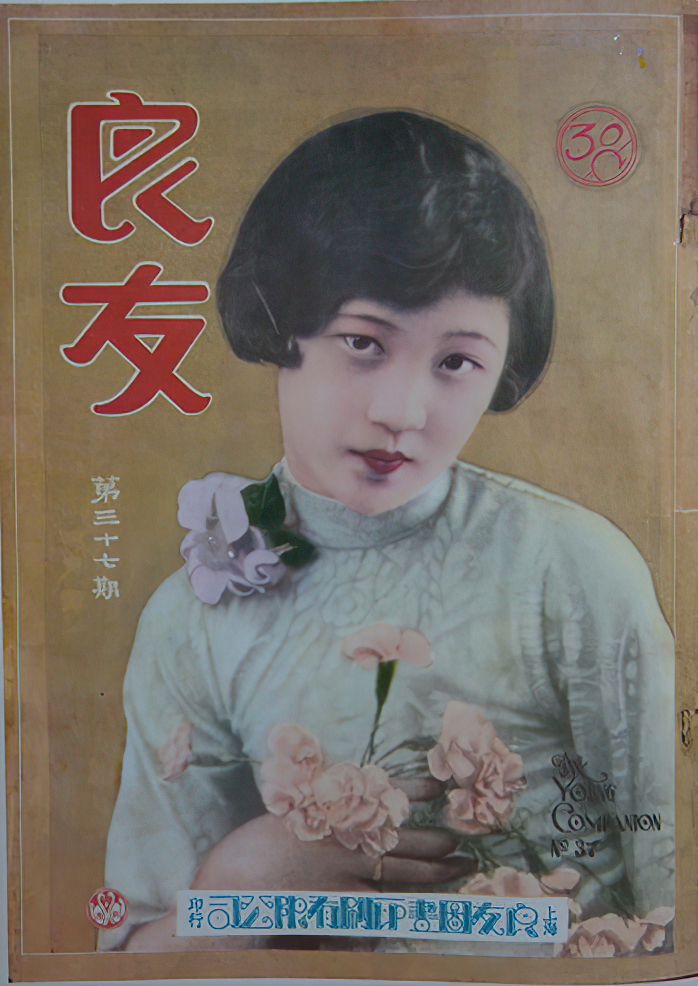

As revealed by Dikotter, consumer goods that were initially seen as outlandishly foreign were not only reproduced and sold in China at much cheaper prices, but also that they quickly found a ready market among Chinese, who, in spite of their reputation as being resistant to foreign products, often put utility and economic value ahead of patriotism. While Chinese consumers were willing to accept Chinese duplicates of western or Japanese products, if goods made in China were deemed inferior when compared to their foreign alternatives, the latter would be purchased in spite of appeals to nationalism issued by various political leaders.11 This wide acceptance of foreign goods in late Qing and early Republication China by consumers from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds was especially evident in the emergence of department stores in Chinese cities such as Shanghai.12 Through the examination of official documents as well as advertisements in periodicals consumed by ordinary Chinese such as Liangyou Monthly, Shanghai’s first major pictorial magazine, Wen-hsin Yeh reveals the wide array of consumption choices available to ordinary Chinese during the Republican period.13 In her study of Wing On, one of China’s first departmental stores, and using as a primary source Wing On Monthly, the store’s catalogue, Ling Ling Lien demonstrates the capacity of merchants to rely upon advisements to attract consumers and secure their loyalty.14 The works of Yeh and Lien highlight the sheer impossibility of rulers to dictate the purchasing choices of ordinary Chinese, as the emerging free market in China ensured that consumers could spend their incomes on goods or brands that most suited their needs.

Average people were therefore capable of deciding which course of action would enhance their interests, especially since there existed a moral code among ordinary men and women and between the rulers and the ruled to ensure that coexistence would be made predictable and tolerable.15 Even in an unequal relationship, the ‘moral standing’ of the stronger party would be ‘contingent on how closely would-be patrons conform to the moral expectations of’ their inferiors.16 A moral code, however, would only be useful to its adherents if there existed a mechanism for enforcement as well as means to punish potential transgressors. Notwithstanding the fact that they did not control the levers of power, ordinary people, as illustrated by James C. Scott, relied upon on acts of resistance that ‘were close to the ground, rooted firmly in the homely but meaningful realities of daily experience’.17 Actions such as ‘foot dragging, dissimulation, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander, arson, [and] sabotage’ constituted ‘weapons of the weak’ operationalized by ordinary people to sanction those in positions of authorities who had abused their power.18

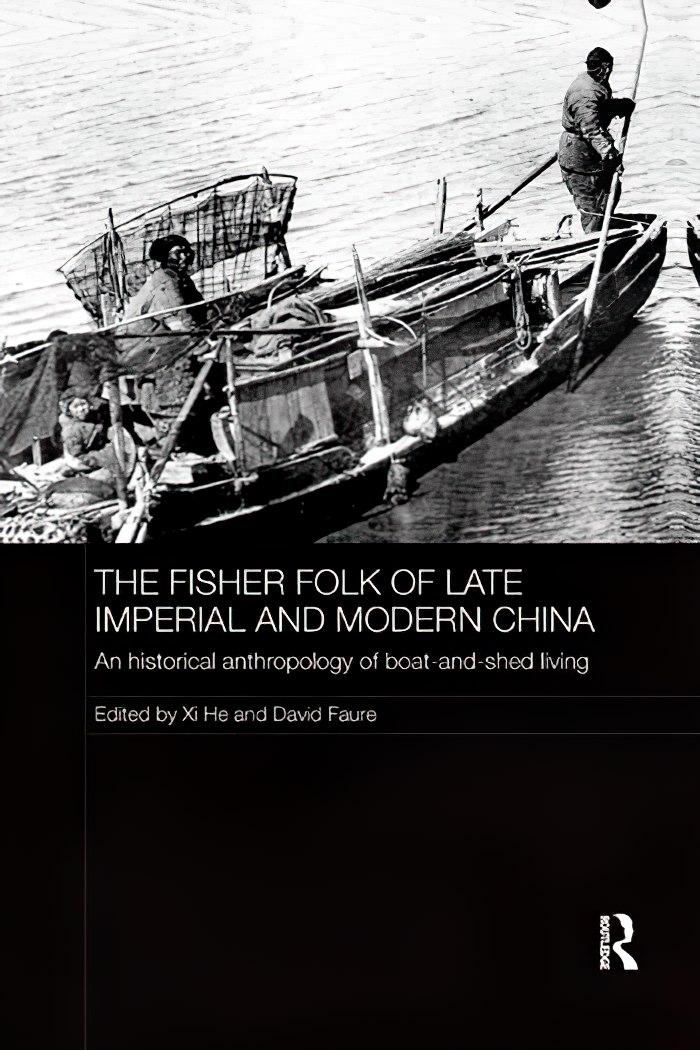

As demonstrated by Michael Szonyi, Chinese of the Ming period, especially members of military households who were responsible for supplying soldiers to the Empire, were able to manipulate official policies to their advantage. The actions of military household members ensured that orders from the imperial court were carried out in such a way that benefited local communities, a critical insight that would have been lost had Szonyi only examined memorandums written by mandarins who were interested in highlighting their successes. Various records left by Ming subjects in familial archives and inscriptions in temples reveals that the burdens of military service were outsourced to family members or outsiders who had consented to being conscripted in exchange for monetary rewards, a practice that complicated the conscription process.19 The ability of the government to recruit the number of soldiers deemed necessary was gradually undermined by the actions of Ming subjects, an outcome that contributed to the shortage of conscripts eventually fatal to the Empire.20 It is therefore imperative for historians to discover how, through their everyday actions, ordinary people either consolidate or fatally undermine governmental policies, religious rituals, or lineage rites. As revealed by a recent volume coedited by Xi He and David Faure that investigates the history of boat people in the coastal regions of China, a group that struggled to preserve their cultural heritages in hostile environments, seemingly insignificant actions such as daily maintenance of a religious practice, if participated by a sufficient number of people over a long period of time, could have immense accumulative effects in the consolidation and the perseveration of a particular way of life.21

Hidden Historical Truths in China and the Everyday Life Perspective

Everyday existences of average men and women contain histories of resilience, resistance, and ingenuity of those who were unwilling to accept values and beliefs that did not benefit them. The everyday life perspective could take China studies to an exciting and innovative direction, one that reveals nuanced historical truths about how ordinary people in the past confronted, survived, and overcame monumental changes and transformations. Often possessing beliefs contrary to ideologies propagated by their rulers, ordinary people could be agents of historical changes as well. The everyday perspective reveals that even average men and women could be history makers, and it is up to historians to uncover their hidden stories.

References

1Wang Jian, Shanghai youtairen shehi shenghoushi (Shanghai: shanghai chubanshe, 2010); Chen Zuen, Riben qiaomin zai shanghai, 1870-1945 (Shanghai: shanghai chubanshe, 2000); Wang Zhicheng, Jindai shanghai eguo qiaomin shenghuo (Shanghai: shanghai chubanshe, 2008).

2Di Wang, The Teahouse: Small Business, Everyday Culture, and Public Politics in Chengdu, 1900-1950 (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2008).

3Hanchao Lu, “The Significance of the Insignificant: Reconstructing the Daily Lives of the Common People of China,” China: An International Journal, Volume 1, Number 1, (March 2003):144-158.

4Chang Jianhua and Xia Ya, zhubian, Richang shenghuo shiye xia de zhonguozongzu (Beijing: kexue chuban she, 2019); Chang Jianhua, zhubian, Zhongguo richang shenghuoshi yanjiu de huigu yu zhanwang (Beijing: kexue chuban she, 2020).

5Alf Lüdtke, “Introduction: What Is the History of Everyday Life and Who Are Its Practitioners?” in The History of Everyday Life: Reconstructing Historical Experiences and Ways of Life, ed. by Alf Lüdtke, trans. William Templer (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1995), 8.

6E. P. Thompson, “History from Below,” The Times Literary Supplement, 7 April 1966, 279-80.

7Ben Highmore, Ordinary Lives: Studies in the Everyday (New York: Routledge, 2011); 164-166, 168-169.

8Prown, “Mind in Matter,” 3, 8.

9Daniel Miller, “Why Clothing Is Not Superficial,” in Introductory Readings in Anthropology, eds. Hilary Callan, Brian Street, Simon Underdown (New York: Berghahn, 2013), 127.

10Prown, “Mind in Matter: An introduction to material culture theory and method,” 17:1 Winterthur Portfolio (Spring 1982): 7.

11Frank Dikotter, Exotic Commodities: Modern Objects and Everyday Life in China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 42.

12Dikotter, Exotic Commodities, 43; Wen-hsin Yeh, Shanghai Splendor: Economic Sentiment and the Making of Modern China, 1843-1949 (Berkley: University of California Press, 2007), 57.

13Yeh, Shanghai Splendor, 65.

14Ling-ling Lien, Creating a Paradise for Consumption: Department Stores and Modern Urban Culture in Shanghai (Taipei, Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2017).

15Michel De Certeau, Practice of Everyday Life – Volume 2: Living and Cooking, trans. Timothy J. Tomasik (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 22.

16James C. Scott, The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press 1976), 170.

17Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985), 32, 36, 348.

18Scott, Weapons of the Weak, 29.

19Michael Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed: Everyday Politics in Late Imperial China (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2017), 16, 66, 83, 122, 191.

20Szonyi, The Art of Being Governed, 23-24.

21Xi He and David Faure, eds, The Fisher Folk of Late Imperial and Modern China: An Historical Anthropology of Boat-and-Shed Living (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Chi-Kong Lai was Reader at the University of Queensland specialising in modern Chinese social and business history. In addition to being an experienced doctoral advisor who has oversaw more than 25 students successfully completing their PhD degrees, Professor Lai is a researcher with an international reputation, as he has published three monographs, eight edited volumes and special issues in journals, as well as 70 journal articles and book chapters. Currently a member of the Royal historical Society, he is the only China scholar to have won the American Economic History Association’s internationally competitive Best Dissertation Award, the Alexander Gerschenkron Prize.

Kent Wan is a lecturer at Nanjing University and is the first Canadian to hold a teaching position at its School of History. An enthusiastic teacher, Kent’s bilingual (Mandarin and English) history seminar, China and the World, 1793-1949, has been well-received by the School’s graduate students. Educated in Canada and Australia, Kent has received academic awards from the National Library of Australia, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and Australian Academy of Social Sciences. A young scholar with a growing research record, his articles, book chapters, and book reviews have appeared in outlets such as The China Journal and Chinese Studies.

Chi-Kong Lai was Reader at the University of Queensland specialising in modern Chinese social and business history. In addition to being an experienced doctoral advisor who has oversaw more than 25 students successfully completing their PhD degrees, Professor Lai is a researcher with an international reputation, as he has published three monographs, eight edited volumes and special issues in journals, as well as 70 journal articles and book chapters. Currently a member of the Royal historical Society, he is the only China scholar to have won the American Economic History Association’s internationally competitive Best Dissertation Award, the Alexander Gerschenkron Prize.

Kent Wan is a lecturer at Nanjing University and is the first Canadian to hold a teaching position at its School of History. An enthusiastic teacher, Kent’s bilingual (Mandarin and English) history seminar, China and the World, 1793-1949, has been well-received by the School’s graduate students. Educated in Canada and Australia, Kent has received academic awards from the National Library of Australia, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and Australian Academy of Social Sciences. A young scholar with a growing research record, his articles, book chapters, and book reviews have appeared in outlets such as The China Journal and Chinese Studies.