In dialogue with Impossible Archives by visual artist Sybil Coovi

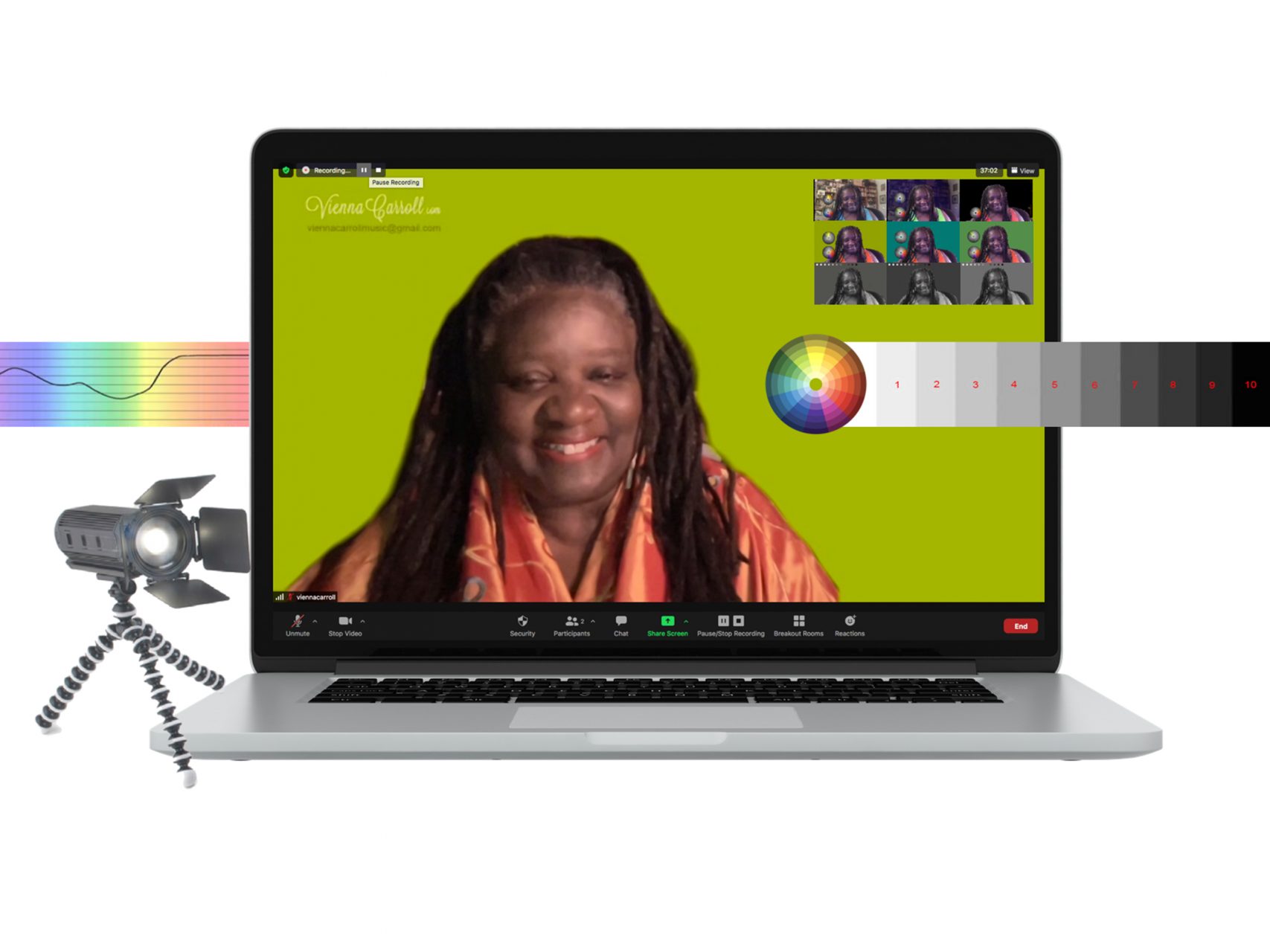

During our second round of tests, lavender filters – which filter out green- outperformed all others, with more pink on Vienna’s and more blue on Richie’s skins.

Introduction: From a Space of Design to a Place of Light

Unbeknownst to most, lighting design is a small and young discipline, yet it is key in our daily lives and cultural experiences due to our species’ dominant visual sense and sensibilities.

Architectural lighting design is the art and science of lighting the human environment. Wikipedia defines it as “a field within architecture and architectural engineering that concerns itself primarily with the illumination of buildings,”[1] but lighting design is a transdisciplinary design profession that is, in fact, distinct from architectural, interior, landscape and urban design, as well as electrical and electronic engineering, yet intersects with all of them. This design discipline integrates knowledge in the natural sciences and the social sciences, as well as technology and engineering. It requires expertise in the physics of light and the physiology and the psychology of light perception by humans, also known as ergonomics or human factors. It is taught at the undergraduate and graduate academic levels, and its practicing professionals come from various backgrounds which include fine arts, design and engineering.

Conventional architectural lighting design practices largely serve a private privileged clientele and established public institutions. By contrast, the think tank PhoScope (Gk. photo “light,”skopos “aim”) was created to take a “socio-photocentric” stance on the built environment, advance the practice, education and critical study of light, and scaffold a new agency for pivotal change and social justice in lighting.

Over the years, PhoScope has become an experimental platform to pursue technical and social innovation and critical study through speculative and practical projects and research. In this context, its projects investigate diminutive and ecological lighting solutions that can empower wide new audiences with lighting knowledge and best practices.

Reclaiming the Greek etymology of light, PhoScope also redefines and repositions the lighting design discipline as Phototecture (Gk. tektōn “builder”) and has developed a lexicon of neologisms that serve as a manifesto for the think tank’s vision and are intertwined with all of its initiatives.[2]

Dermaphotology: From a Space of Light to a Place of Skin

In one project, I used Photology – the branch of physical science that studies the properties and phenomena of light – to propose the hypothetical sub-discipline “Dermaphotology” (Gk. derma “skin”) in order to study light and skin and to explore and expose the “color of light” in our lighted lives.

This project began a few years ago with my friend Vienna Carroll, a formidable singer who delivers resonant jazz tunes in cafes and restaurants, but whose masterful appearance is oftentimes reduced to a dark silhouette. The dimmed ambience created for the comfort of evening diners provides inadequate (if any) lighting to ad-hoc stage settings that are punishing for her darker skin tone.

I realized that Vienna was not getting the visual presence that she deserved, and that by extension, many people of color were likely performing in similarly inadequate places of darkness and were left in a space of technological oblivion. As a result, I started developing a solution in the form of a a portable light fixture that Vienna could easily carry in her purse and use to illuminate herself with the right light- for her skin tone.

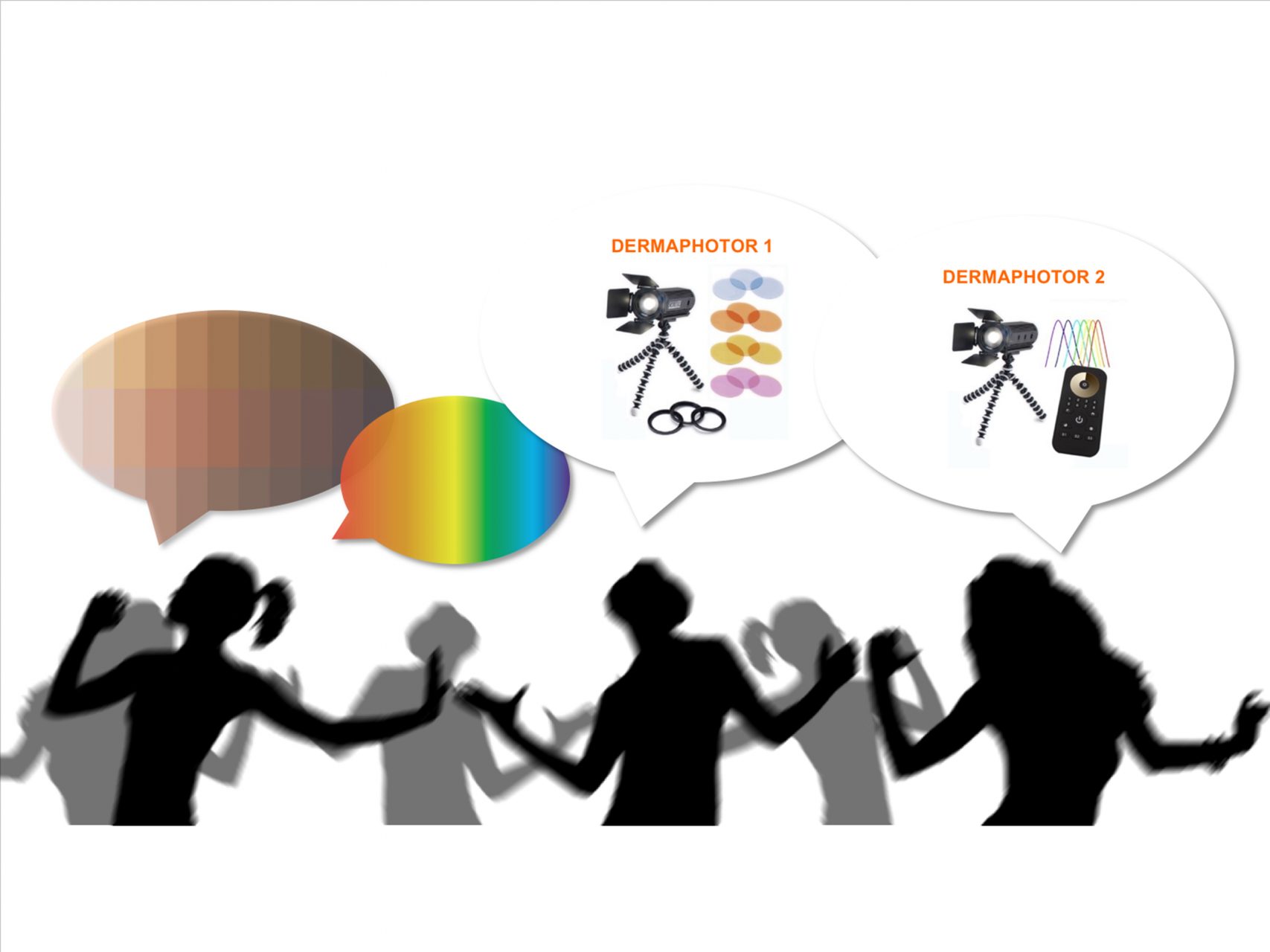

Moreover, “Dermaphotor” is conceived as a versatile lighting tool that is affordable, portable, and rechargeable – including by solar power – to shine the right light on performers of any skin tone. It is synchronously conceptualized to be worn as a lighting accessory for additional artistic and cultural applications—for instance to light the space of the dancing or theatrical body, in addition to or in place of stage lighting. The COVID-19 pandemic and our expansive use of online platforms to communicate and perform virtually also provided an opportunity to explore its use beyond the physical space of performance.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the scope of “Dermaphotor” was expanded to serve OPOC (Online Performers of Color) with the right light.

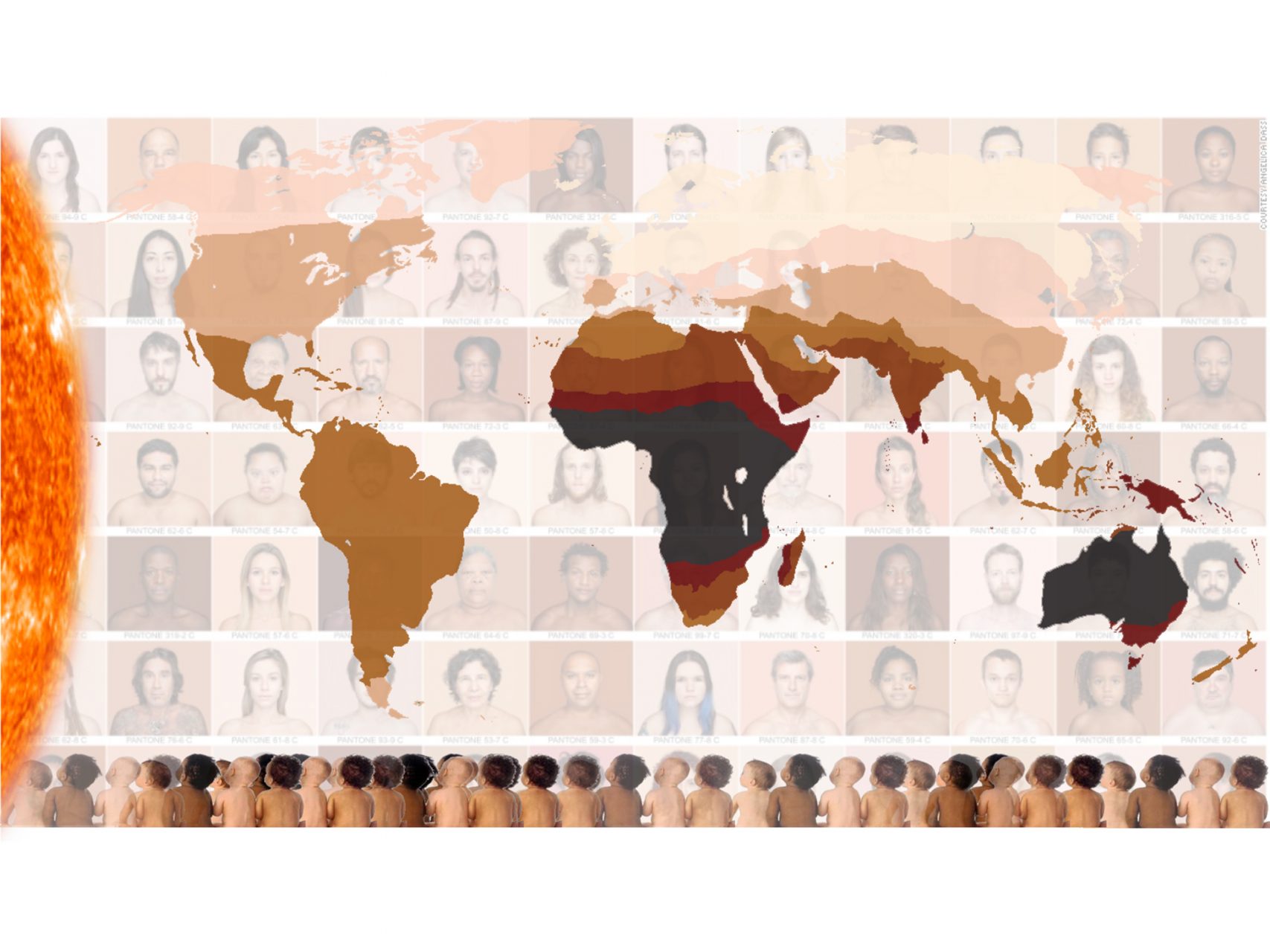

Our ancestral history and geographic location explain the richness of our skin tones which optimize the benefits and minimize the impact of our exposure to UV wavelengths.

“Dermaphotor” is proposed to empower POC (Performers of Color) with the right light, and is conceived as a diminutive lighting tool that is affordable, portable, and rechargeable– including by solar power.

“Dermaphotology” and “Dermaphotor” are technical and sociocultural endeavors that bridge applied research and critical study in multiple disciplines across design, science, and the humanities. I have now pursued preliminary scholarly, design and technical research as well as conducted initial tests with Vienna for proof-of-concept and to outline the schematics of the project’s framework and methodology, and the time has come for a team.

I have engaged project advisors and potential partners from intersecting fields – e.g. cultural anthropology, cinematography, lighting design etc., and in the next steps, I will assemble a technical team and a sample of volunteers and steer a psychophysical study. It will include a series of spectrophotometric experiments to test and measure existing and modified light sources versus skin reflectance. As a collective, the technical and advisory team will recruit volunteers – subjects and observers; help frame the study’s settings; collect feedback from observers; and analyze and synthesize all resulting data. The study’s findings will be interpreted and used to sketch a conceptual design framework towards further project development and prototyping.

In addition, as we expend research and conduct an extensive literature review, I expect we will encounter more intersections between lighting and social research that will expand the topic’s intrinsic transdisciplinarity and the project’s critical study.

From a Space of Diversity to a Place of Equity

Lighting may seem like an unassuming area of query, but it is transdisciplinary and transcalar by nature, and it offers a compelling vantage point to study how the built environment affects democratic life. Not only will rethinking light improve the appearance of all skin tones and critique and reverse the inherent built-in discrimination that pervades practice and theory in today’s visual and spatial disciplines, but it will also contribute to the dissemination of the current science of skin tone.

In recent years, the work of biological anthropologist and paleobiologist Nina Jablonski has shed much needed light on the evolution of human skin and skin pigmentation as a biological trait with health consequences. In Living Color, she deconstructs the falsehood of races as biological entities by retracing the biological evolution of variations in skin pigmentations and the historical establishment of races. In her concluding statement, she writes: “Motivation is critical to the elimination of color-based discrimination. The bodies of understanding we now have about skin color need to be matched by the will to change. This is a process in which no one is a spectator: we are all participants.”[3]

Among these participants are the practitioners and thinkers of the spatio-visual disciplines that construct and analyze our environments, stages and screens. As in all things constructed, the cultural history of light production and applications entails complex political, cultural, economic and social forces, and new studies are needed to deconstruct biases for new best practices to emerge.

Notably, the biases that have long been built in the lighting products and practices of the film and media industries have now come to light, and new techniques and discourse have emerged to correct the fair-tone bias that had long driven the metrics of skin color balance. For instance, researcher and professor of Communications Lorna Roth has been studying the representation of skin color in history. In “The Colour Balance Project,”[4] she describes how she identified whiteness as a cultural bias embedded within many technologies and products that deal with skin. While she questions the production and marketing of “presumed innocent” products that perpetuate racialized imagery in the industry of photography: “Although they appear to be insignificant initially, these silences and absences inform and frame our knowledge of race relations at this stage of history,” [5] she also sets her larger project goals: “Conceptually, I would like to introduce the notion of “cognitive equity”— that is, a new way of understanding racial equity issues that does not only revolve around statistics, legislation, or access to institutions, but rather inscribes directly a vision of multicultural and multiracial equity into technologies, products, and emergent practices in their usage.”[6]

Conclusion: From a Space of Enlightenment to a Place of Light

We all shine in broad daylight. The optical properties of skin tone may be complex, but the absence of resolve in the presentation and representation of our diversity is cultural and not technological: artificial lighting has historically plagued the rich colors of people’s diverse skin pigmentations.

The objectives of “Dermaphotology” are to expose the structural prejudice built in the everyday lighting technologies and products throughout our spatio-visual practices, embrace the esthetics of skin and visual equity, and bring forth a new quality in the presentation and representation of all people of color within our everyday environments, stages and screens.

Beyond spatial design disciplines such as product, interior, architectural, landscape and urban design, this project uniquely intersects with technology, science and the arts – performing, visual and media arts – and the humanities.

Art and design are powerful vehicles for social change, and by addressing the color of light, the hypothetical field of “Dermaphotology” as well as the lighting tool “Dermaphotor” will have a real-world impact: a new quality in the presentation and representation of all people of color and a new discourse will manifest and inform many of the creative and reflective practices that enlighten our lives and expand our minds.

Impossible Archives, by Sybil Coovi

Ethnographic exhibition of Hottentots. Date taken: 1888. Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

[Group of Hottentots. Four men standing, wearing animal skins, bare chests. They are dressed in animal skins. One man is lying down, wearing feathers and an animal skin cloth. He is shirtless. He is barefoot. A man crouching. His arms are crossed on his knees. He is dressed in an animal skin].

Donor: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Anc. Coll. of the Musée de l’Homme – Photothèque. New coll. of the Musée du Quai Branly – Iconothèque

For almost ten years, Sybil Coovi has been experimenting with representations of the black body in photography, continuously questioning the imposed perceptions, forms and fantasies, as well as their discrepancies with the artist’s own history(s), certainties, doubts, daily life, spaces and self. During her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Bourges, Sybil Coovi began a research project on French colonial history born of a collection of images on the imagery of the “black body”. Ranging from “scientific” accounts and texts on the notion of race, to classification documents and travelogues, she was confronted with the processes of staging and exhibiting those who are signalled as “Others” through photographs taken during colonial exhibitions in Europe.

” Confronted with this ‘type’ of photography, which seeks to establish a strict regulation of the figure of the ‘savage’, I have developed an artistic production in which the processes of forming and erasure of images, but also the extensive forms of their exhibition, are displaced in order to make visible what is at stake for me: the staging, the setting, the absence of real presence. Through “gestures” I intervene on the photographs, seeking to extract these bodies, these people, from the exhibition of fantasized representations. “ – Sybil Coovi

Paï-Pi-Bri- (Jardin d’acclimatation).

Ethnographic exhibition of Paï Pi Bri: 1893.

Date taken: 1893.

Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Silver bromide gelatine negative on a glass plate turned positive. Plate of 18 x 24 cm.

[Portrait of two women standing. The woman on the left is wearing cloths from neck to head which hide her whole body. She is barefoot. She is wearing a cloth on her head and a necklace].

Donor: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Anc. Coll. of the Musée de l’Homme – Photothèque.

New coll. of the Musée du Quai Branly – Iconothèque.

(Hottentots (Jardin d’acclimatation)

Ethnographic exhibition of Paï Pi Bri: 1888.

Date taken: 1888.

Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Silver bromide gelatine negative on glass plate turned positive.

Plate size 18 x 24 cm.

[A child standing in profile. He is naked and wears a necklace around his neck. He is barefoot].

Donor: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Anc. Coll. of the Musée de l’Homme – Photothèque.

New coll. of the Musée du Quai Branly – Iconothèque.

Ethnographic exhibition of Paï Pi Bri 1893.

Date taken: 1893.

Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Silver gelatin silver bromide negative on glass plate turned positive.

Plate of 18 x 24 cm.

[Portrait of a full-length man, standing, leaning against the back of a chair. He is bare-chested. He is wearing a rope collar and holding another collar in his hand].

Donor: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Anc. Coll. of the Musée de l’Homme – Photothèque.

New coll. of the Musée du Quai Branly – Iconothèque.

Ethnographic exhibition of Paï Pi Bri 1893

Date taken: 1893.

Photographer: Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Print on albumen paper mounted on cardboard.

Size of the print : 21 x 12,8 cm.

[Portrait of a woman standing, front view, bare chest. She is wearing a scarf on her head].

Donor : Prince Roland Bonaparte.

Anc. Coll. of the Musée de l’Homme – Photothèque.

New coll. of the Musée du Quai Branly – Iconothèque

Article endnotes

[1] Rozot, Nathalie. POV.

[2] PhosWords are available in English, Spanish and French and forthcoming in Portuguese https://www.phoscope.org/do/phoswords/

[3] Jablonski, Living Color, 197.

[4] The Colour Balance Project

[5] Roth, Looking at Shirley, 116

[6] Roth, 127

Article references

Jablonski, Nina G. Living Color: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Color. Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2012.

PhoScope. Accessed March 7 2022, https://www.phoscope.org.

Roth, Lorna. “Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity. Canadian Journal of Communication.” Vol 34 (1): 113-35. 2009.

Rozot, Nathalie. POV. July 5 2012. “What is architectural lighting design?” http://archive.pov.org/citydark/architectural-lighting-design/

“The Colour Balance Project.” Accessed March 7 2022. http://colourbalance.lornaroth.com/

Nathalie Rozot is a New York-based phototect and the founder of PhoScope, think tank on light.

Awards and distinctions include a 2021 Women in Lighting International Award for the global solar lighting initiative Light Reach; awards from the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America and of New York City, grants from the City of Paris, the New York State Council for the Arts, the New York State Energy Research and Development Agency and the New School University; fellowships from the Graham Foundation for Architecture, the MacDowell Colony and the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA); and sponsorships from NYFA and the Van Alen Institute.

She has taught lighting in several Masters programs, and she publishes and lectures globally on social and critical issues in lighting.

Born in 1988 in Paris (FR), Sybil Coovi Handemagnon graduated from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’art de Bourges after studying visual communication in Paris. She lives between Paris, Lyon and Villentrois. Multidisciplinary artist, Sybil Coovi Handemagnon combines photomontage/photography, sculpture, installation and writing in her work. Her works have been exhibited in the exhibitions Poétique(s) de l’inachèvement and <Jardin de las mixturas. Tentativas de hacer lugar, 1995-…> at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, during the exhibition Futuribles at the Arthothèque de Strasbourg, during the exhibition Fantôme.s Résitant.e.s at the galerie l’Inattendue in Paris, during the exhibition Medium(s) at Hasard Ludique, among others.

Nathalie Rozot is a New York-based phototect and the founder of PhoScope, think tank on light.

Awards and distinctions include a 2021 Women in Lighting International Award for the global solar lighting initiative Light Reach; awards from the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America and of New York City, grants from the City of Paris, the New York State Council for the Arts, the New York State Energy Research and Development Agency and the New School University; fellowships from the Graham Foundation for Architecture, the MacDowell Colony and the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA); and sponsorships from NYFA and the Van Alen Institute.

She has taught lighting in several Masters programs, and she publishes and lectures globally on social and critical issues in lighting.

Born in 1988 in Paris (FR), Sybil Coovi Handemagnon graduated from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’art de Bourges after studying visual communication in Paris. She lives between Paris, Lyon and Villentrois. Multidisciplinary artist, Sybil Coovi Handemagnon combines photomontage/photography, sculpture, installation and writing in her work. Her works have been exhibited in the exhibitions Poétique(s) de l’inachèvement and <Jardin de las mixturas. Tentativas de hacer lugar, 1995-…> at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, during the exhibition Futuribles at the Arthothèque de Strasbourg, during the exhibition Fantôme.s Résitant.e.s at the galerie l’Inattendue in Paris, during the exhibition Medium(s) at Hasard Ludique, among others.