(This text was written in the margin of the Tryspaces project.)

“… rainy night Mexico City of the present contains no roses and no fresh hot donuts and it’s bleak….”

“… the whole of Mexico a Bohemian Adventure in the great outdoor plateau of night of stones, candle and mist….”

Tristessa, Jack Kerouac

One

The city is a gray, all-eating monster when you walk out of the subway into a neighborhood you don’t know. What do you look for there? A familiar face or gesture? What do you search for when the city is a mundane teddy bear (the one from your childhood, maybe) and you’re bored of its soft gaze?

Tristessa is a novel about searching. It is one of the two texts that Jack Kerouac (beatnik extraordinaire) wrote in and about Mexico City (Mexico City Blues was the other one, published in 1959). Tristessa chronicles, through a jazz-pulse narration and Buddhist-infused reflections, the comings and goings of Kerouac in Mexico City, as well as his friendship with a group of junkies, among whom stands out the india Tristessa, whose real name was (ironically enough) Esperanza, Spanish for “hope.” Tristessa reads like the bleak diary of a man spiritually lost in a city he loves and hates at the same time, in which he reflects on his relationship to drugs, to his Buddhist beliefs, and to Tristessa, who he loves and desires, but he shuns carnal pleasure and love in search of spirituality.

The members of the beatnik generation were united by their drive, or devotion, to searches or quests. To read them is to set our eyes on a utopic horizon—a free life, lived “on the road,” contrary to modern Americanized life. For Kerouac, as well as other beats (like Burroughs), Mexico was a place of pilgrimage, sanctuary, and freedom:

Mexico a great city for the artist, where he can get cheap lodgings,

good food, lots of fun on saturday nights (including girls for hire)

where he can stroll the streets and boulevards unimpeded and for that

matter at all hours of the night while sweet little policemen look away

minding their own business which is crime prevention and detection.[1]

In Tristessa, two searches take place inside the narration. These are the quests of the characters. A third one, the quest of Kerouac himself, takes place in the meta-text. The first search, which is more material, is the quest for dope (specifically morphine), undertaken by the characters throughout the streets and slums of Mexico City. This quest is a constant in the novel and (besides getting high) one of the main activities of the characters. The second quest, of a more spiritual nature, is the search for “nothingness,” nirvana, a place that, unlike this earth, doesn’t have pain, temptation, or suffering. This is mainly the narrator’s quest (also Kerouac’s, in a sense), but the search for a higher order is not confined to the narrator’s interior monologue—several other characters are also on a quest of this kind, including Tristessa and Dave, who once a year undertake a spiritual pilgrimage to Chalmas:

… once a year together they’d take hikes to Chalmas to the mountains

to climb part of their knees to come to the shrine of piled crutches

left there by pilgrims healed of disease, the thousand tapete-straws

laid out in the mist where they sleep the night out in blankets and

raincoats—returning, devout, hungry, healthy, to light new candles

to the Mother and hitting the streets again for their morphine….[2]

The quest for drugs and the quest for spirituality are intertwined in the novel, with pilgrimagethe key word that binds both searches. The wandering around the city in the search for morphine is a pilgrimage like the one carried out by Tristessa and Dave, as well as the pilgrimage of the beats themselves, who traveled throughout the world committed to finding somethingthat modern life couldn’t offer them. The purpose of both searches is to find/consume that which enables the transcendence of the plane of the “real,” be it spirituality or drugs.

The third quest has more to do with what Kerouac looked for as a writer. This would be, in this novel as well as most of his work, the search for a different form of narration—a narration not akin to a canon, or to the idea of “literature” in general, but to a personal search for an aesthetic able to convey one’s true, pure emotions. This search is apparent in the way that Tristessa is structured, like a mechanical and deambulatory flow of language whose purpose is not so much to develop a cohesive story but to explore ideas and feelings as if they were the streets of an unknown city.

Two

To think of literature as mimesis is to undermine it. All literary creation is, in my opinion, just that—creation, a space from which another space, another reality, and another language sprout. Tristessa paints a Mexico City that is not the “real” Mexico City, but rather a territory created, filtered, and interpreted through the thoughts and feelings of the character and person that is (or was) Jack Kerouac.

The space that we read and that the characters inhabit in Tristessa only exists in its pages. Kerouac’s Mexico City is, in a way, intertwined with his feelings, his spirituality, and his pain:

The construction of a mythical vision of Mexico in the work of the

Beatniks that derives from the particular way in which they

approached their stays in the country; the mythical Mexico they

describe is a non-existent geographical space, constructed through

the assembly of small valuations, of imaginary representations that

constantly permeate the texts; Mexico is constructed as an

imaginary space that corresponds or responds to what

the authors of the texts expect or think of the country.[3]

The Garibaldi Plaza of Tristessa is not the Garibaldi Plaza we can point to on a map, or the one we can physically visit. It is, instead, a place where “strange crowds around quiet musicians” gather, where the sounds of marimbas plague the air, and rich and poor people gather alike. It’s a place where “lovers of the loving Mexican night” lean against a wall to look at the prostitutes walking by. Space, through the lens of Tristessa, is fiction.

Kerouac is a highly romantic storyteller. That’s why the Mexico City we read in Tristessa is a place that existed in the interior and, at the same time, reflected Kerouac’s interior life. Kerouac transgresses “real” space by juxtaposing it with his personal, interior space, thus creating the new space that exists in Tristessa. This is not a transgression that only Kerouac carries out, but a transgression that, I believe, is present in every novel and every other form of literary expressions, with the exception of naturalist novels. However, even naturalist texts frame “reality” and space within a subjective framework. Literature, in a sense, filters “reality” through emotion, feelings, metaphor, etcetera, in order to create a new “reality”—“The text does not necessarily represent a world discursively or conceal a world behind it but creates a world in front of it.”[4] And this world that the text creates in front of it is not merely confined to a precise moment, which in this case would be the moment-of-reading. Instead, it is a creation that extends through time. Our reading of a space in text doesn’t stop when we close the book, but continues even as we lay down the book and decide to go for a walk and we start to read space through text. “Texts are not mere inscriptions on a surface, but actors and throbbing energies which participate in fashioning the world.”[5]

In Tristessa, the mythic Mexico City that Kerouac creates not only rises from the juxtaposition of “real” and interior space, but also from the juxtaposition of the “here” and “there”:

I go down the Wild Street of Redondas, in the rain,

it hasn’t started increasing yet, I push through and dodge

through moils of activity with whore by the hundred lined

up along the walls of Panama Street… the whores are nooking

the night with their crooking fingers of Come On, young men

pass and give em the once over, arm in arm in crowds the young

Mexicans are Casbah buddying down their main girl street…

the whole of Mexico a Bohemian Adventure in the great outdoor

plateau night of stones, candle and mist.[6]

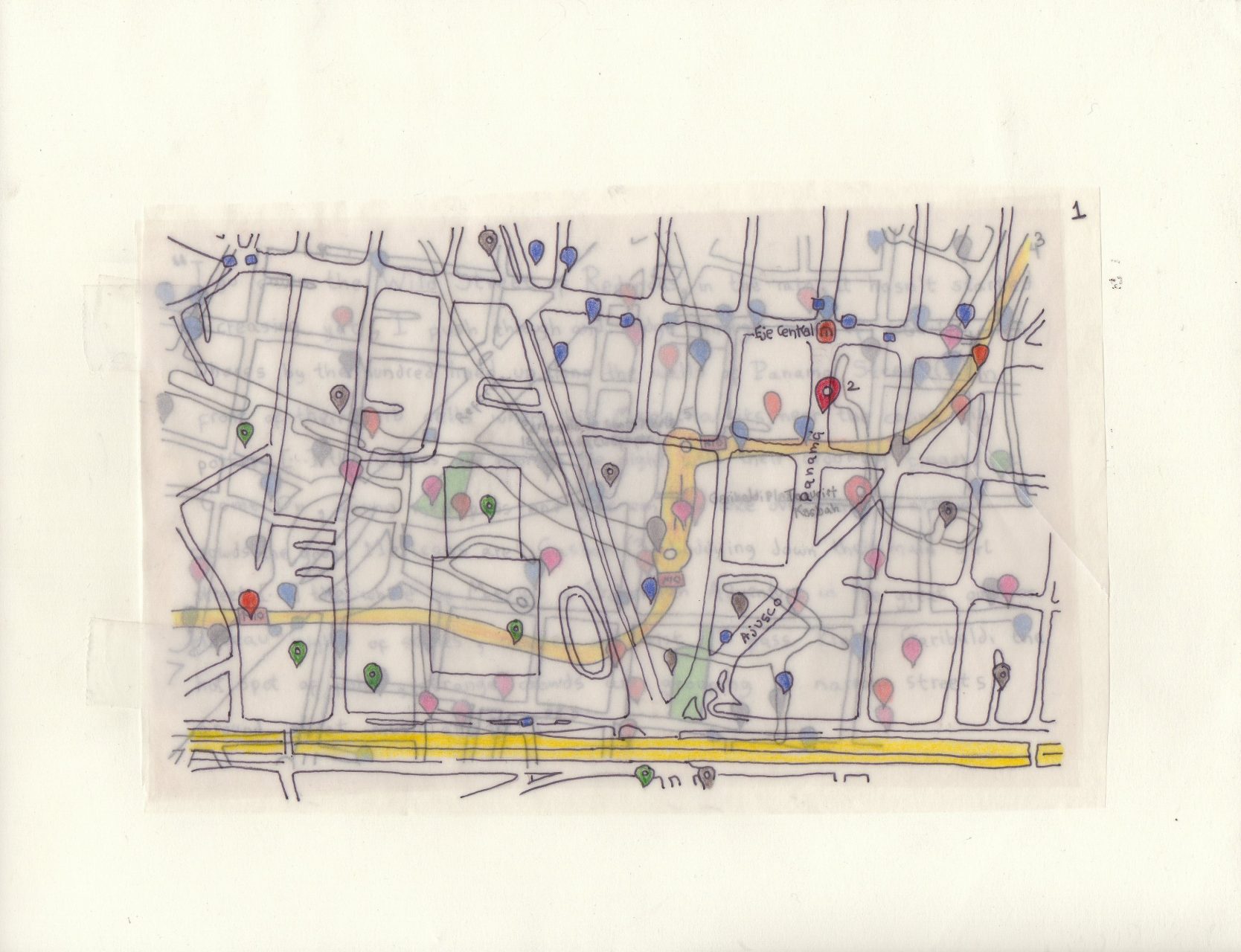

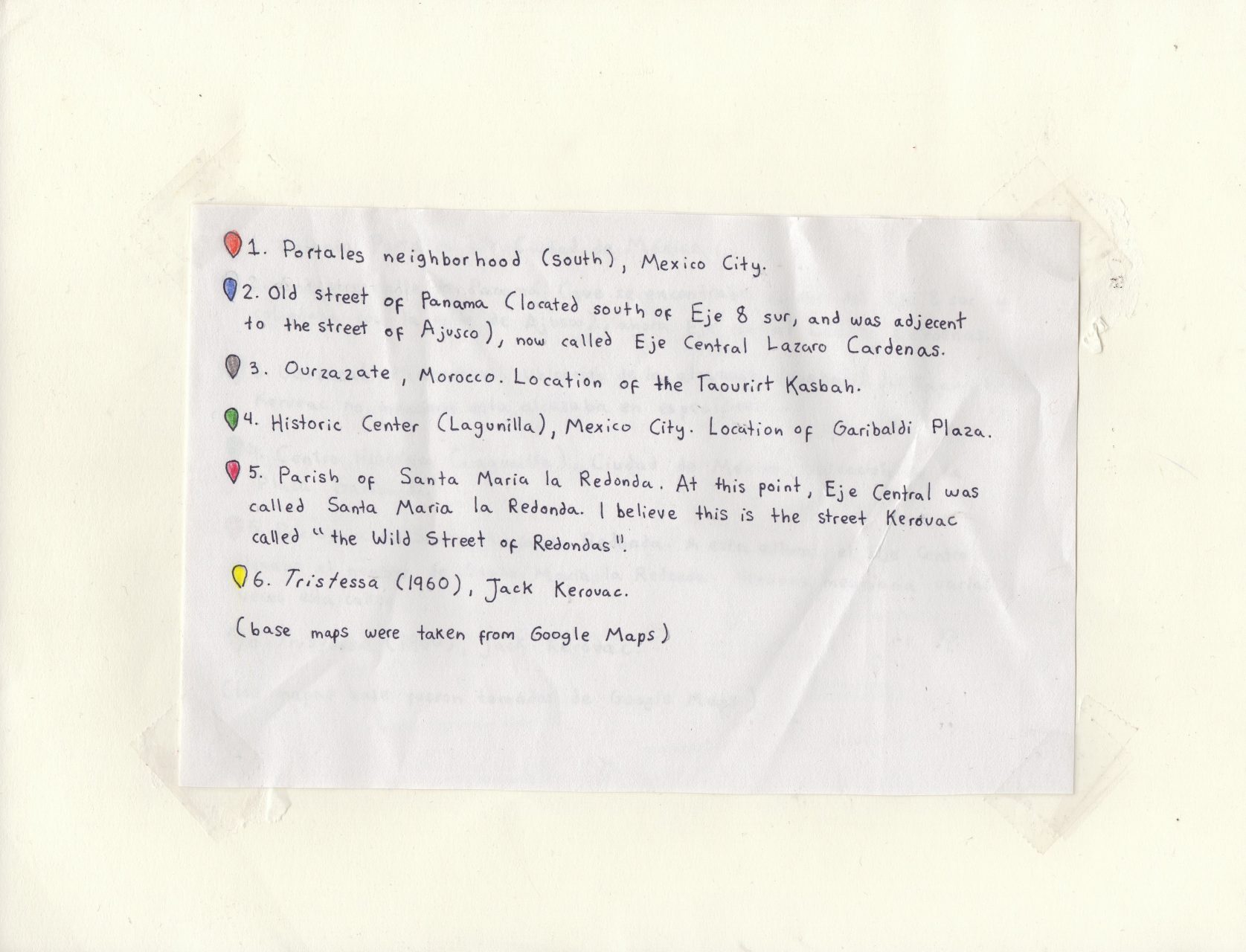

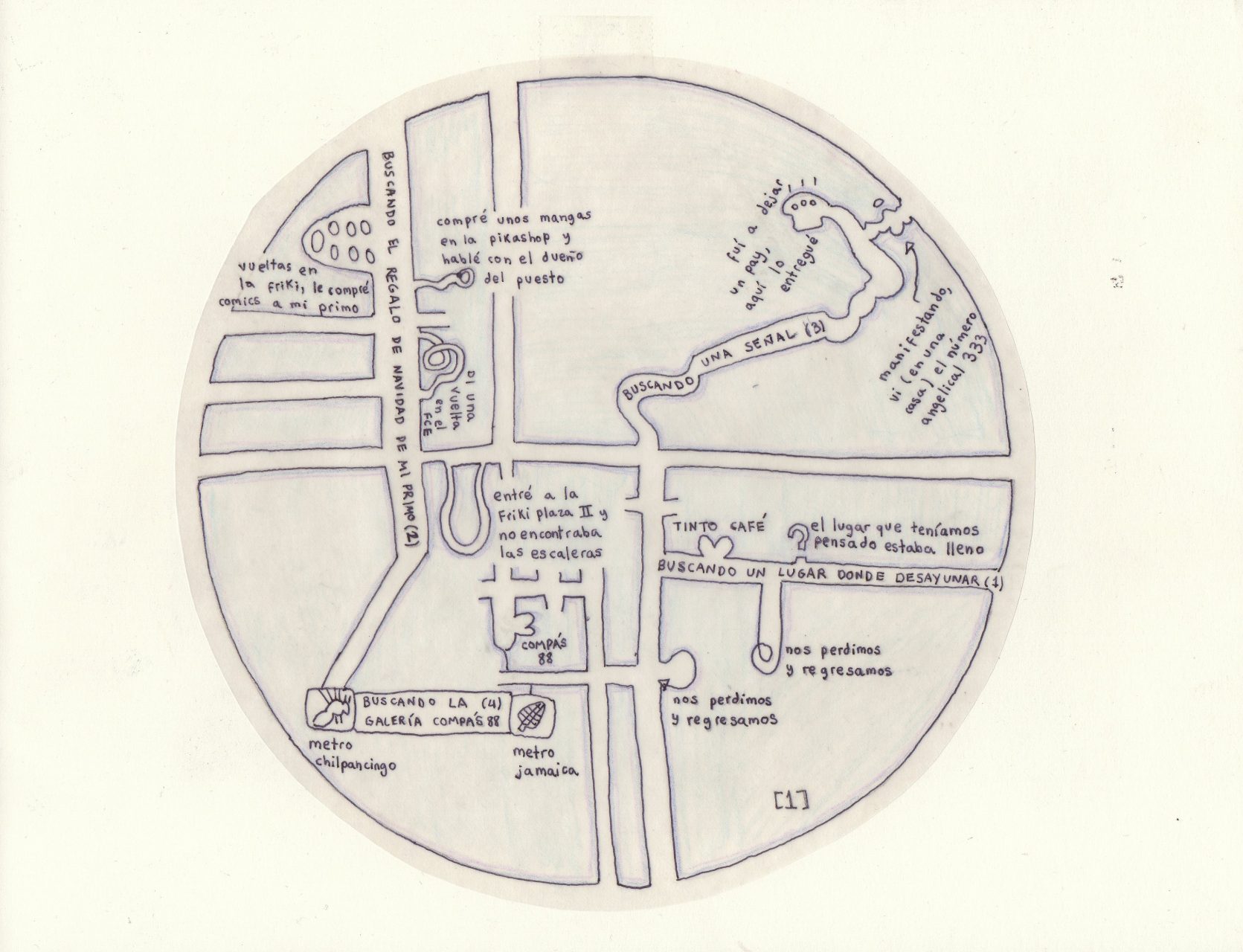

(see Map One)

Kerouac continuously places (textually) places on top of each other, as in this quote, in which a street in México city, Panama (now Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas) is juxtaposed with a kasbah. More than comparing places, Kerouac creates a sort of path or band between which these two places communicate and flow into each other. “Their space, the ‘Beat’ space, if we can call it that, is a space formed by a collection of apparently disjoint elements… in such a way that they create, through the pages of their works, a fragmented continuity of spaces that intertwine, respond to each other, traverse each other, and also get mixed up.”[7]

I go down the Wild Street of Redondas […] (juxtaposed map)

In Tristessa, Mexico City ceases to be just the material city and becomes a place traversed by various other cities, stimuli, and memories. The city is no longer what we held so unbreakable—that which we see—and becomes instead fragments, a circulatory space whose base isn’t material, nor are its sidewalks or streets, but instead memory made through space: “Thus, the spaces are not those that a traditional geographer would be pleased to describe: they’re virtual spaces, virtually integrated in a baroque, bizarre and shocking whole, but magnificently representative of a profound sense of modernity.”[8]

Three

How to carry out a mapping of search? What would our understanding and experience of the city become if we walked the city like Kerouac and his characters? Wandering around, not in a flaneuristic manner, but thinking in the key of a quest—crossing through random streets, knowing that that which we’re looking for possesses no specific location, but can be found anywhere in this huge behemoth of a city. It would be useful to think in the key of the Situationists dérive. As I see them, the travels of the characters in Tristessa are pure action and movement in search of a certain psychogeographical stimulus: “In a dérive one or more person during a certain period of time drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their usual motivations for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractiveness of the terrain and the encounter they find there.”[9] This is Kerouac walking around Eje Central and seeing Nirvana in its crowded sidewalks. It’s also Tristessa walking around in a morphine haze, being drawn to anything that looks or sounds like it could get her closer to the salvation of a new shot.

Then, a cartography of the search through the dérive would be to drift around the city in the search of certain stimuli, symbols, or signs. This map would be a reflection of our desires, from the deepest to the most superficial, mundane ones—a reflection of that which we search for daily, for that also reflects (sometimes unconsciously) our inner lives:

… the primarily urban character of the dérive, in its element in the great industrially transformed cities that are such rich centers of possibilities and meanings, could be expressed in Marx’s phrase: “Men can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves. Their very landscape is alive.”[10] What color would our quests paint in the city? Would it be gray like Kerouac’s? Or would it be a different color altogether?

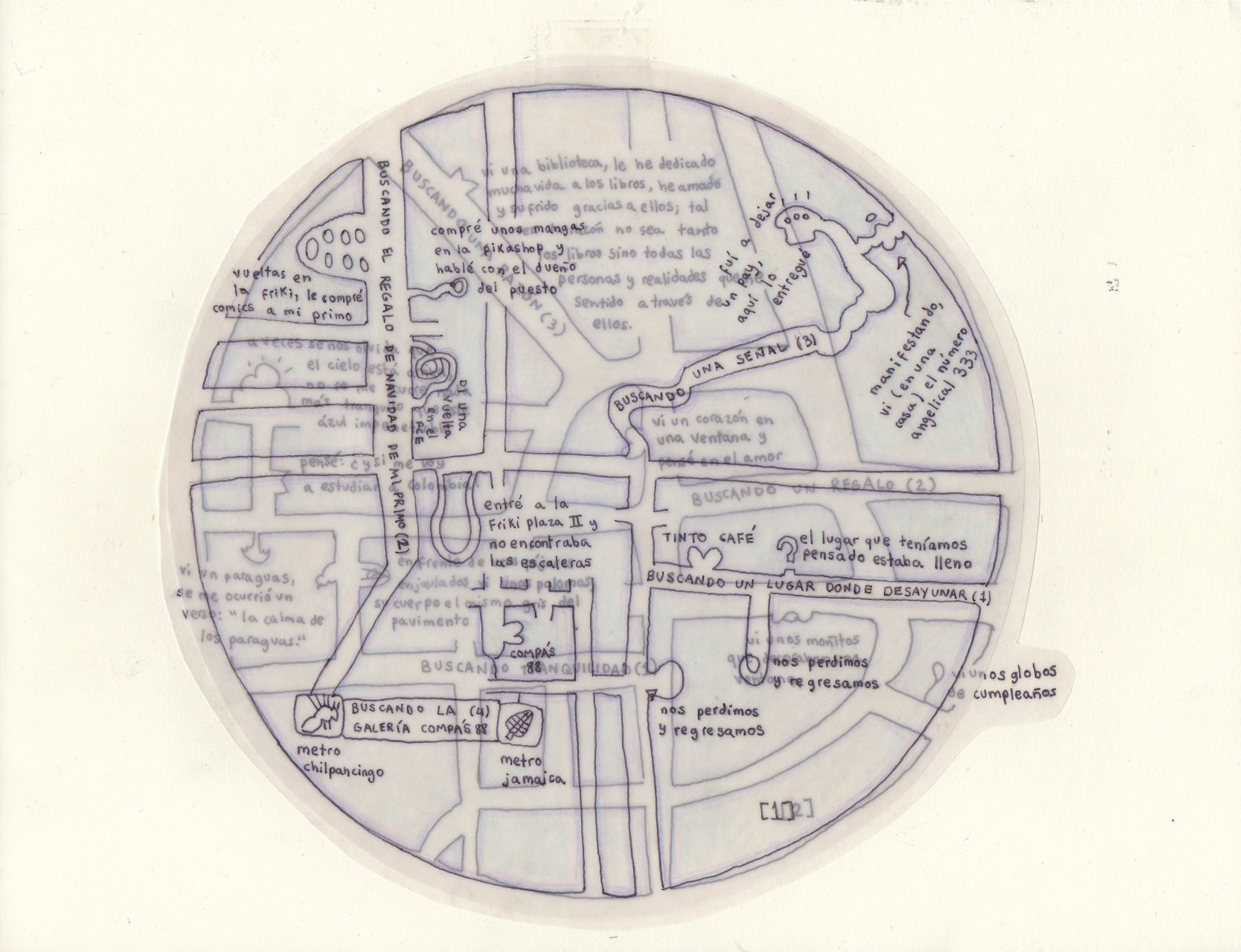

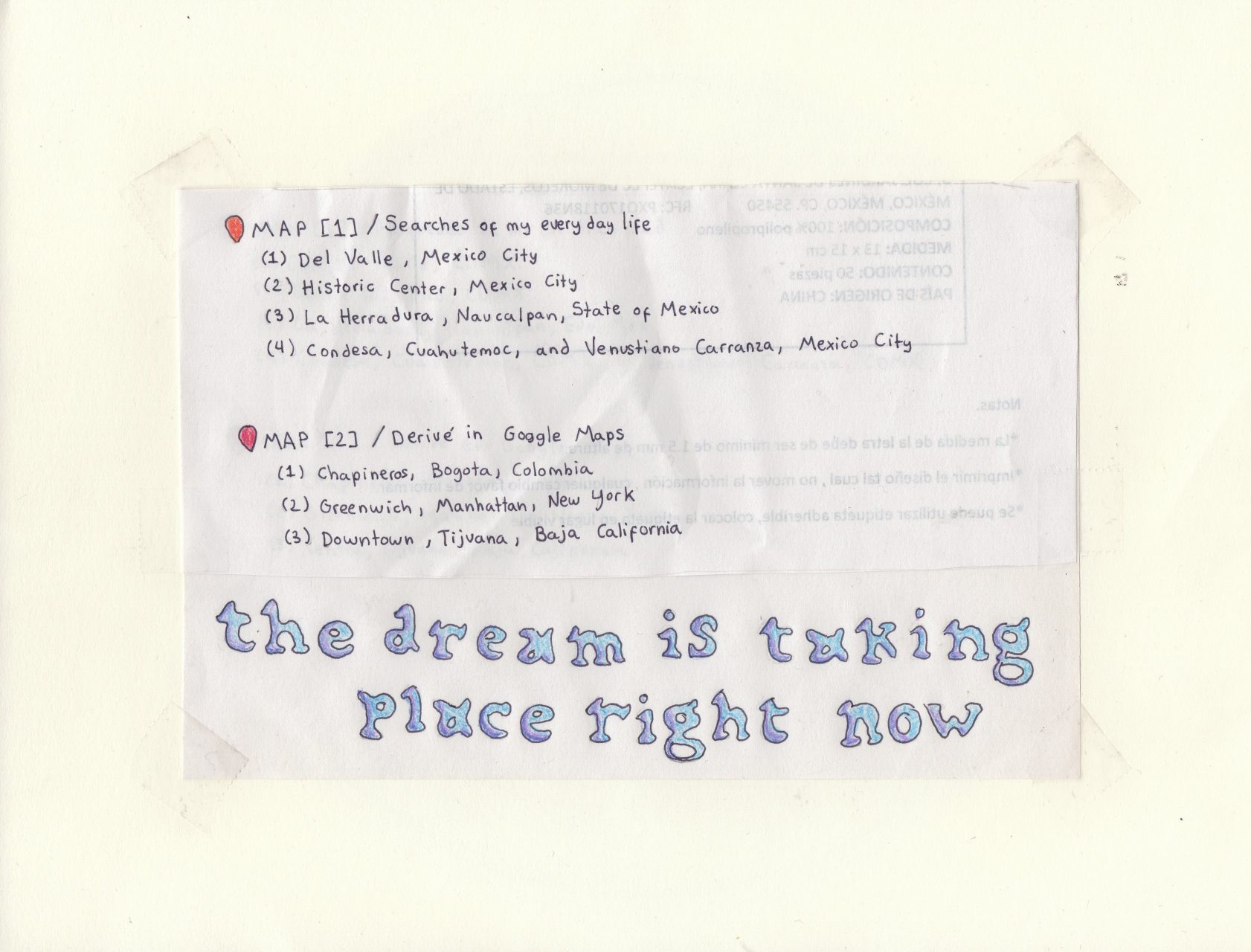

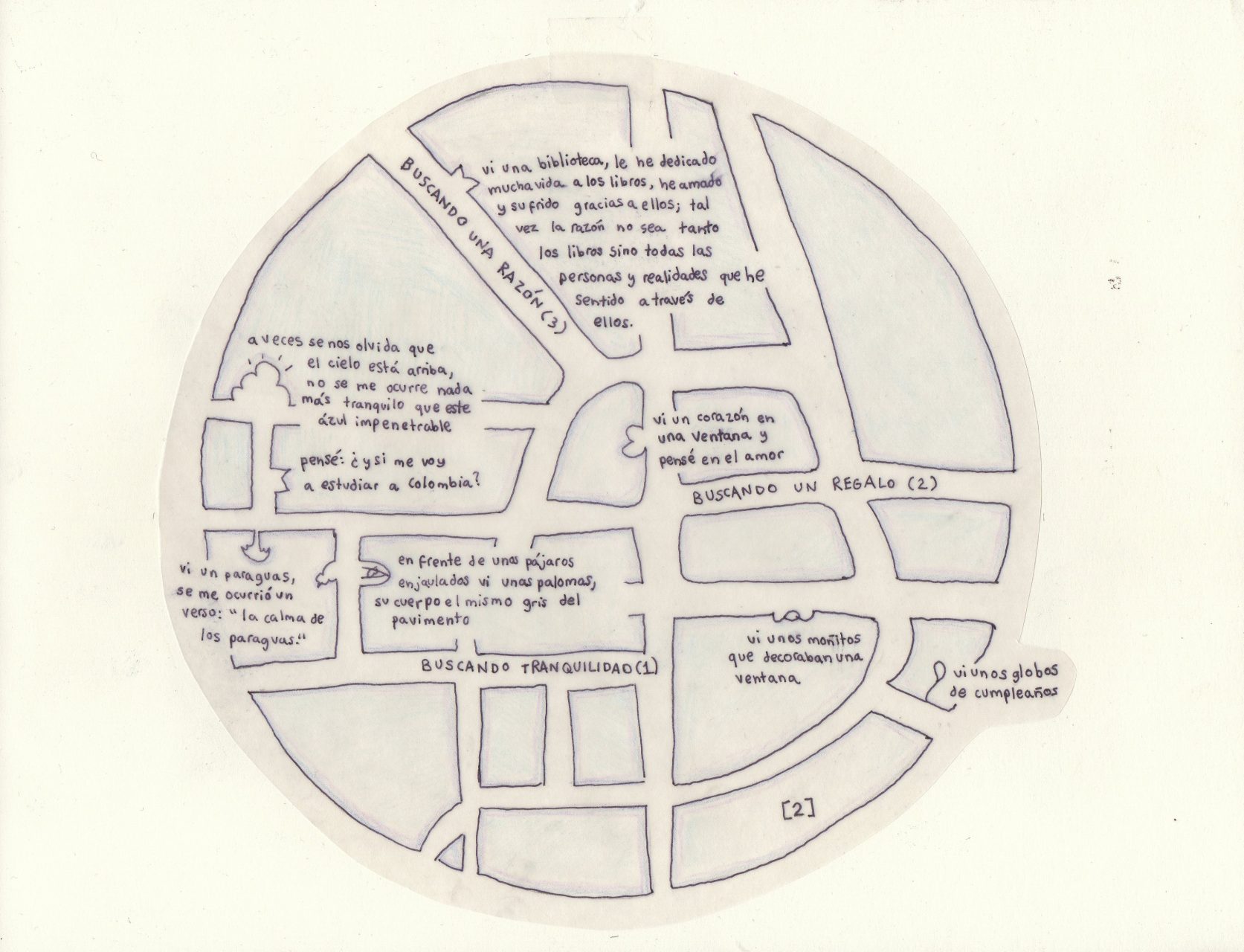

I made a map that arose from my reading of Tristessa, and all of the questions that arose from those readings but, more specifically, how to portray a city through, or rather made by, search?

I’ll give a brief insight into the making of this map so that it can be reproduced by anyone that wishes to explore their city in a similar manner. I split this mapping into two levels. The first level (the map on top) is composed of daily searches, and shows the streets I walked, the places I visited, the movements I made, and a small text that details what I was searching for and what I did in my journey (e.g., “I got lost here,” or “Here I entered the mall and couldn’t find the stairs.”). By being conscious of the way I move through the city, I began to see that my daily transit was composed of more searches than I thought—that time we got lost (momentarily) at Mercado Jamaica because we couldn’t find the gallery we were looking for, that time that I walked up and down (almost like Kerouac) Eje Central looking for the Batman comics that my cousin wanted for Christmas, or that time we ended up walking hazily down a long road looking for a place to have breakfast in because the place we had looked up was already full.

On the second level (the map on the bottom), I tried to show a more conscious search, developed by dérive, that responded to certain emotions or feelings. I have to point out that the dérives in this mapping took place, not in the material city, but in Google Maps. I wanted to drift like Kerouac, who strolls through la Roma but imagines himself walking down New York City, and so, from my home in Mexico City I imagined myself walking through the streets of Bogotá looking for peace, through the streets of Greenwich Village looking for a gift, and through the streets of downtown Tijuana looking for a reason. The small texts detail things I thought of or felt while searching—on my quest for peace I saw the blue sky and thought of how often we forget the calm, infinite, sea of wind we have above us. While searching for a reason, I saw a library, barely two minutes into my dérive, and thought of how much of my life I’ve devoted to books, and that if I had to choose a reason it would be them, and all the lives I’ve lived through and in them.

Within this map, different spaces of Mexico City, and other cities in the world, are juxtaposed, intertwined, and linked, much like the circulatory place that Kerouac and his characters inhabit in Tristessa. To drift, to partake in a dérive, is to eliminate frontiers: “… it is no longer a matter of precisely delineating stable continents, but of changing architecture and urbanism…. The most general change that derive experiences lead to proposing is the constant diminution of these border regions, up to the point of their complete suppression.”[11] In this map, and in Tristessa, the streets do not maintain their material limits. Instead, they merge into one another, and are presented to us as an incomplete and nameless space. This is not to render space unimportant, but to understand that we do not inhabit the city-space in a singular, universal way, not even within the limits of our personal, everyday life.

Four

I looked for words to close this text, but I can’t find them. What I want from this text is for it to be an input for the creation of search mapping. A gateway for understanding the city differently than just “where I am” and “where I need to be.” A different way of looking at our journeys, of understanding that the city-space is not understood (nor constructed) in a singular, total way, and of understanding that literature plays a big part in the way that this space is built and thought of—maybe not just literature, but all of our inner and private feelings and quests. But I’m starting to get lost in my own words now, much like Tristessa drifting around a Mexico City that only Kerouac knew, but was kind enough to share with us. Maybe you can find the closing words somewhere in what has already been said. I’ve already laid out a small city of words for you here. From this distance I can see a street made up of nouns, a sidewalk made of verbs, and a small room upon a rooftop made out of metaphors. Inside, a figure hunched over a table, and the sound of a city being written away.

References

Aijaz, Abdul. “Worldly texts and geographies of meaning”, Literary Geographies, Vol.4, No. 2 (2018), pp. 150-155.

Debord, Guy. “Theory of the Dérive”, in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb, (California, Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), pp. 62-66.

Hiernaux-Nicolas, Daniel. “México: el espacio mágico y efímero de los beats”, Casa del tiemp, Vol. IX, No. 100 (July-September 2007), pp. 32-41.

Kerouac, Jack. Desolation Angels. New York: Putnam’s, 1980, quoted in T. Jones, James, “Kerouac in Mexico, Mexico in Kerouac”, in Map of the Mexico City Blues. Southern Illinois University Press, 1992.

Kerouac, Jack. Tristessa. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

Footnotes

[1] Jack Kerouac, Desolation Angels (New York: Putnam’s, 1980), as cited in James T. Jones, 1992, p. 60.

[2] Jack Kerouac, Tristessa, (New York, Penguin Books, 1992), p. 11.

[3] Daniel Hiernaux-Nicolas, “México: el espacio mágico y efímero de los beats,” Casa del tiempo, Vol. IX, No. 100 (July-September 2007), p. 34 (my translation).

[4] Abdul Aijaz, “Worldly texts and geographies of meaning,” Literary Geographies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (2018), p. 151.

[5] Ibid., p. 151

[6] Jack Kerouac, Tristessa, (New York, Penguin Books, 1992), p. 26.

[7] Daniel Hiernaux-Nicolas, “México: el espacio mágico y efímero de los beats”, Casa del tiemp, Vol. IX, No. 100 (July- September 2007), p. 39 (my translation).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (California, Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), p. 62.

[10] Ibid., p. 63.

[11] Ibid., p. 66.

Santiago Gómez Sánchez is a writer from Mexico City. His work as a poet has been published in literary magazines such as Estroboscopio, Himen, Cardenal, Melancolía Desenchufada and Fósforo. His essay “en el punto inmóvil del mundo que gira” was presented at the exhibition “¿Cómo se genera una ola?” organized by Oleaje at the Museo de la Ciudad de Cuernavaca in september 2021. He’s part of Penca Poetica, a collective focused on the act of reading and hearing poetry. He’s interested in the way literature shapes and creates space, and in the unconscious way we read reality through text.

Santiago Gómez Sánchez is a writer from Mexico City. His work as a poet has been published in literary magazines such as Estroboscopio, Himen, Cardenal, Melancolía Desenchufada and Fósforo. His essay “en el punto inmóvil del mundo que gira” was presented at the exhibition “¿Cómo se genera una ola?” organized by Oleaje at the Museo de la Ciudad de Cuernavaca in september 2021. He’s part of Penca Poetica, a collective focused on the act of reading and hearing poetry. He’s interested in the way literature shapes and creates space, and in the unconscious way we read reality through text.