In dialogue with

the photographic project Rupture, Un espace-Temps

by Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon and Jean-Louis Rullaud

.

As early as the 1950s, writers of the Nouveau Roman had sensed that the traditional novel was floundering, that its mechanisms—the position in which it placed the reader, its characters, its realism—were idling, and that emerging symbolic practices were more fitting for the turmoil of the “Age of Suspicion.” In those days, film photography still managed to evade suspicion. However, half a century later, after the emergence of digital photography, distrust had caught up with analogue photography for its ability to splice images and words together with events. Now, more than ever, digital technology has allowed for images and words to exist entirely separate from the things they represent. Digital photographs are neither true nor relevant, nor do they thrive on the margins of the “real world.” They are documents on the loose, adrift in an era of doubt.

.

Documents on the loose

Following the Second World War, the photographic document benefited from the momentum surrounding the illustrated press (newspapers and magazines), analogue photojournalism, and the figure of the news correspondent. The world was under reconstruction and people were eager to reclaim their destiny, to return to a form of order around values such as rationality, rigour, and transparency. These values, by all accounts, had been infused into a number of artistic, architectural, and photographic works, as well as the ethics and aesthetics of the photojournalists of the time—the golden era of film photography’s truth document.

Confronted with a world they perceived as chaotic, reporters of the time attempted to establish a centre, to find a sense of order. Some of them, in a rather modern stance, strove to capture the essential truth of the time, hidden in the depths of reality, within the folds of a shifting multiplicity of events. They carried out this mission with an ordering and ruling eye, following an aesthetic which led them to eliminate, trim, and simplify world events in order to capture graphically-composed photographs in so-called “decisive” moments. This, along with the notion of the imprint, was the predominant doxa in documentary film photography until the end of the 20th century. It went hand in hand with the aesthetics of objective distance, transparency, purity, and immediacy. The elements of those aesthetics are well known—ascetic, clean-cut forms, a lack of fancy effects, sharpness, balanced lighting, an obsession with composition, and of course a categorical disapproval of cropping, all played a part in the endeavour of sanctifying the instant. Above all, photography meant composition and geometry.

The 20th century was the age of certainty and the golden age of film photography. We were certain there was a world we could render. But then that world collapsed. At the dawn of the 21st century, documenting reality and fictionalizing it are no longer mutually exclusive. Press photography has taken an overtly postmodern turn. From one era to the other, journalistic ideals and practices changed, as have photography and the world itself.

Through analogue photography, reporters of the past century represented the visible world by submitting it to rationality through geometrical composition, the “decisive instant,” and aesthetic clarity. Whereas representation through film photography was about organizing, controlling, and ordering the visible world by geometrizing it, digital photography attempts to capture forces, to “make invisible forces visible.” What was once banished from analogue photojournalism has become the norm within digital photography. Blurriness, shadows, staged situations, and the demise of geometry all warp the image’s inherent descriptive and denotative qualities. In addition to creating staged situations as a means of bargaining with reality, an abundance of editing, cropping, and fine-tuning techniques have come to shatter the notions of truth and transparency. Because it lends itself so well to the infinite possibilities offered by editing and enhancing—to the confusion between truth and falsehood and to fake news—digital photography is perfectly aligned with our current time.

.

Fake news, true-false truths

Digital photography has punctured the concepts of the document and of truth so deeply that the once-indisputable distinctions between true and false have become uncertain. The document has gone rogue, and truth, plagued by so-called “alternative facts,” has become plural and unclear. Yesterday’s truth was expressed in the singular form, and shared analogue photography’s rigour and fixity. In a way, today’s truth shares digital photography’s fluidity and the impermanence of its life on social media. If “truth is inseparable from the mechanism that established it,” then it is certainly undergoing transformation in our current visual “chaosmos.” Since the dawn of the 21st century, the direct imprint offered by analogue photography has been overthrown by the network truths put forth by digital photography.

.

Network truths

Let us recall the sadly notorious photographs taken by American soldiers during the war in Iraq (2002) inside the Abou Ghraib prison in which Iraqi fighters were being held captive. These photographs revealed the horrors committed by the American jailers—torturers who were seen posing and bragging beside prisoners undergoing the vilest acts of humiliation and brutality. Having been committed within the fortified enclosure of the prison, closed off to any exterior gaze (especially to journalists), these images could only have been shot by the torturers themselves, using digital cameras. The photographs were likely sent to only a few friends online, and then one friend sent them to another, and that friend to yet another. We owe the rest to the extraordinary power of network acceleration and transmission. Having been sucked into the network, the newly uncontrollable images ended up being published in newspapers and magazines around the world, for all to see.

It is the apparatus of digital photography—instantly capturing, publishing, and propagating images—that revealed this shocking reality and produced a network truth, a gaze-less truth. Of course, the protagonists of the event had contributed to this truth, but they did so unknowingly, against their will, as if they had been trapped by the power and velocity of digital photography’s global record-and-transmit apparatus.

The role digital media plays in the production of truths, and which presented itself so shockingly in 2002, has become significantly stronger since the rise of smartphones and social media. More than ever, truths regarding world events are the simultaneous product of the digital photographs that capture the images and the digital networks that spread them across the globe in real time. Back in the days of print press and analogue photography, image capture was the linchpin in the production of truth, regardless of technical hindrances (slow-paced technology or physical constraints such as limited print runs, heavy material). The photojournalists of the 20th century were mediators between the world and the general public. Their technically-trained and culturally-informed gaze allowed them to professionally select events and things that were relevant to the world by giving them meaning, despite that fact that their detached, distant, and sometimes domineering gaze was in fact formatted, meaning selective—simultaneously clairvoyant and partially blind.

.

Infra-amateur truths

Nowadays, the photographs we see most are ones that circulate thanks to the anonymous crowd of new actors who we shall call “infra-amateurs.” They are neither professionals nor amateurs; they share the common trait of owning a smartphone and, for the most part, have no prior technical or aesthetic knowledge. Their photographs are generally taken in haste, almost arbitrarily, with no control, often captured in motion, without a viewfinder, and paying no attention to framing.

Because of how much content they produce, how numerous and how omnipresent they are on social media, these infra-amateurs now rival professional photojournalists, with their agencies, gaze, knowledge, ethics, and aesthetics.

The infra-amateurs are inventing a new regime of truth. Ever since smartphones became ordinary accessories, it has become possible to instantaneously capture and broadcast any event in the world as it unfolds, either by participants or onlookers. Infra-amateurs are onlookers, participants, and sometimes even victims of the events they photograph. Contrary to the time-lagged images produced by the removed and external gaze of the professional photojournalists, the images of the infra-amateurs are directly connected to the events they capture. They have an immediate contact with online social networks, and are free from economic, technical, or aesthetic restraints. This explains why their shots may seem closer to the truth, rawer, more authentic—more real—than photographs made by professionals. This is a direct consequence of the newly-instated regime of truth that is implicitly based on immediacy, on the raw and uncontrolled aesthetics of the image, and on real-time sharing through network media. Infra-amateurs therefore directly rival photojournalists and the media system, by opposing a spontaneous, uncontrolled image capture to an expression of meaning through professional, technical, and aesthetic means. At the image-capturing stage, infra-amateurs transform the gaze, aesthetics, temporality, and distance at play in photography. At the publishing stage, network media accelerates the image’s circulation, and grows its audience to a planetary scale. With their Immediacy, proximity, accessibility, and horizontality, network media, smartphones, and digital photography are together enabling the rise and propagation of new truths that challenge established knowledge, order, and power.

Alongside these network truths, which do not undergo any validation protocol or process, social media has seen an abundance of nonsense flourish on the internet, also known as fake news. Never before have truth and falsehood been so tightly intertwined. This is in part due to a new king of falsehood—digital photographic fakes created through software like Photoshop.

.

Fabricating falsehood

Created in 1990 by the American company Adobe and currently installed on most computers, tablets, and smartphones, Photoshop and its multiple imitators and variations expresses and invites its users to experiment with the systemic shift of images from the realm of truth into the realm of falsehood. Whereas a series of technical and aesthetic constraints and protocols once preserved the presumption of veracity for analogue photography, this software embodies the fundamentally fictional, artificial, manufactured, and malleable nature of digital photography.

Strengthening the ideal of documentary film photography required promoting the fable of the photograph as a direct imprint of reality—mechanically, objectively, and intangibly recorded onto the photographic substrate. It also required rejecting all altering effects of technique as well as lab work. In other words, it required limiting the photographic process solely to the imprint of a situation onto film, with the photographer acting as the warrant of the image’s indexicality.

The situation with digital photography is exactly the opposite. The shooting devices, smartphones and computers included, are equipped with software like Photoshop, which allows users to view and edit photographs. Visualization and editing are blurred into one and the same gesture, meaning images are always edited. With that, falsehood has been implanted inside truth. The “age of suspicion” and the “age of doubt” have mutated into “the age of falsehood.” The imprinted truth, which relied on the trust afforded to paper or film analogue photography, is now superseded by network truths based on hyper-exposure and on high-velocity dissemination of images and information. Truth is no longer a given nor a guarantee. Rather, it is to-be-created within the midst of an overflowing stream of signs. Truth has become an uncertain matter—a byproduct, the froth of falsehood.

Discover the full project Rupture, A space Time

André Rouillé is a professor and researcher at the University of Paris VIII. Since 2002, he has directed the website paris-art.com, which is devoted to art, photography, design and dance. He has published 8 books on the history and aesthetics of silver photography, which have been translated into English.

His latest essay, entitled La photo numérique, une force néolibérale, was published in 2020 by L’Echappée (Paris).

Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon, has a degree in architecture and has gradually turned to photography, with a keen interest in spaces under construction, in destruction and in abandoned spaces. He divides his time between Paris and Bordeaux.

Jean-Louis Rullaud trained at Ecole Boulle, then at ESDI (Ecole Supérieure de Design Industriel), and has worked in graphic communication, advertising, printing, and architecture. Since 2008, he has been developing a plastic and photographic practice. He lives and works in Bordeaux

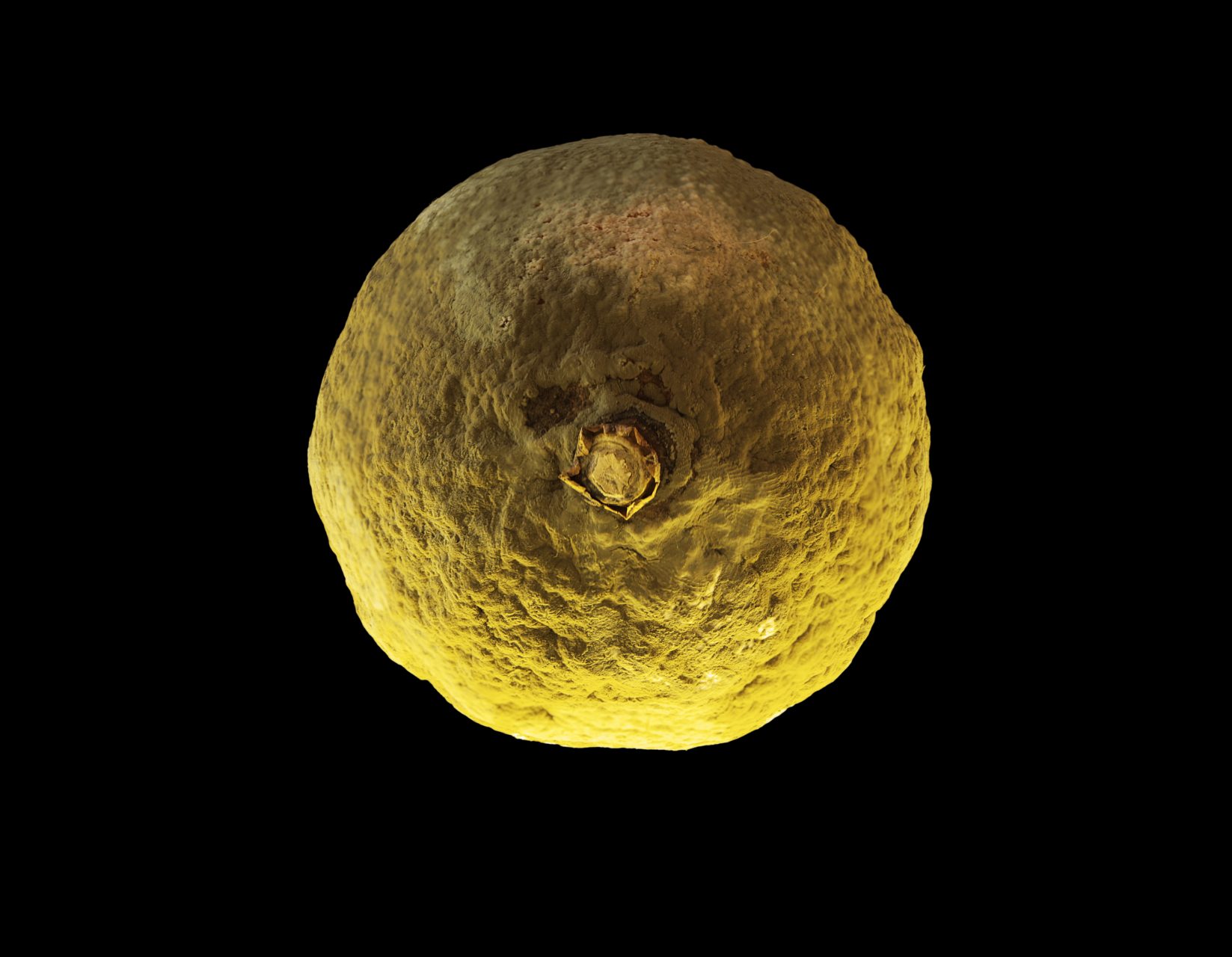

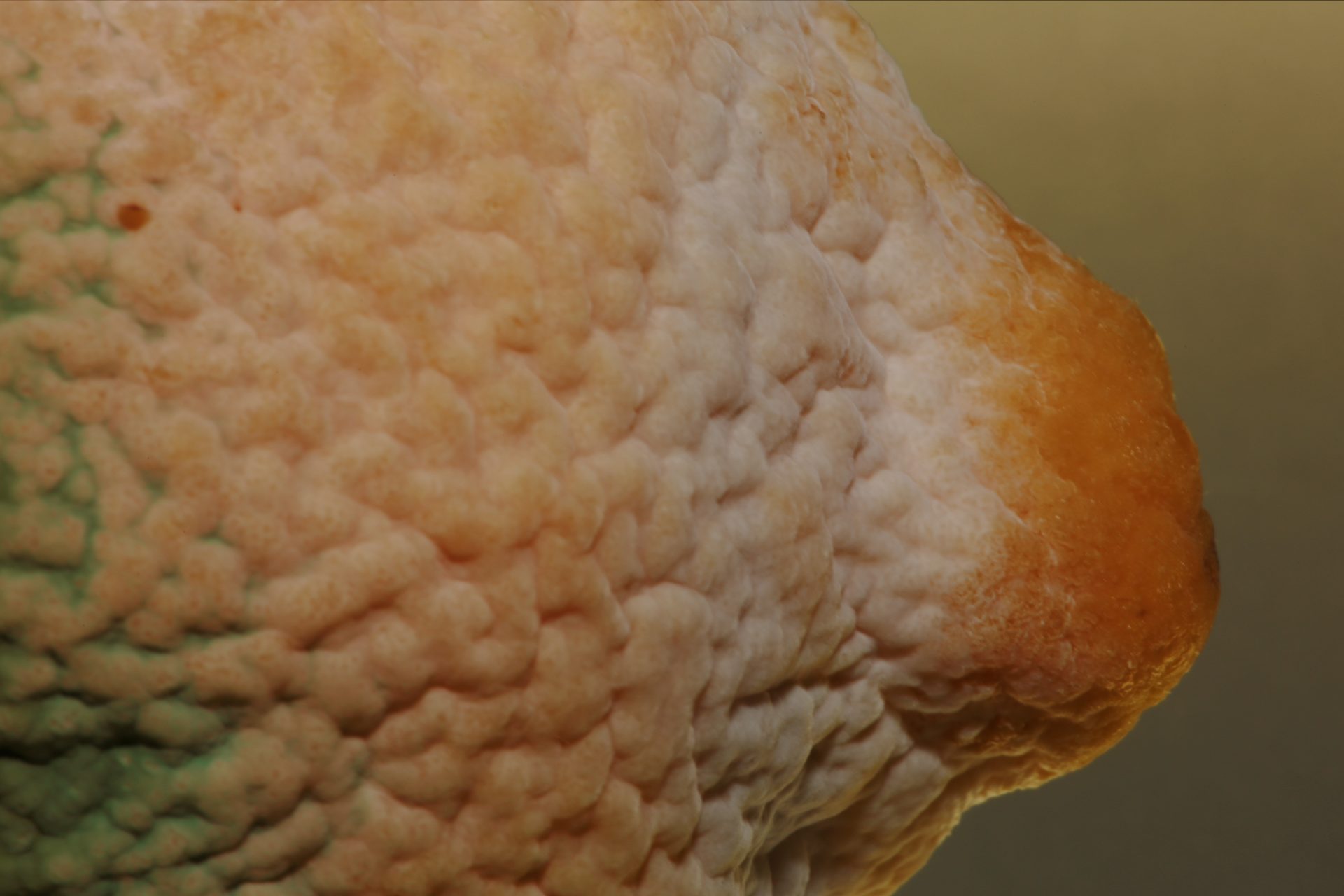

RUPTURE- A SPACE TIME

Through their respective works, Jean-Louis Rullaud and Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon question the notion of rupture as a temporal space, opening a field of possibilities in the interpretation of the living and its relationship to its environment. The moment of rupture is brought upon by the photographers, in an optimistic perspective, to be understood as a mutation of beings and things. Nothing is lost, everything is transformed. This project was presented in May 2018 at Mémoire de l’Avenir.

Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon’s black and white series of analog photographs were made with a 4/5 inch camera, and his series of digital coloured images were taken with a Nikon D3.

Jean-Louis Rullaud took his photographs with a Canon 5D Mark3 digital camera and processed the images with digital tools.

André Rouillé is a professor and researcher at the University of Paris VIII. Since 2002, he has directed the website paris-art.com, which is devoted to art, photography, design and dance. He has published 8 books on the history and aesthetics of silver photography, which have been translated into English.

His latest essay, entitled La photo numérique, une force néolibérale, was published in 2020 by L’Echappée (Paris).

Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon, has a degree in architecture and has gradually turned to photography, with a keen interest in spaces under construction, in destruction and in abandoned spaces. He divides his time between Paris and Bordeaux.

Jean-Louis Rullaud trained at Ecole Boulle, then at ESDI (Ecole Supérieure de Design Industriel), and has worked in graphic communication, advertising, printing, and architecture. Since 2008, he has been developing a plastic and photographic practice. He lives and works in Bordeaux

RUPTURE- A SPACE TIME

Through their respective works, Jean-Louis Rullaud and Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon question the notion of rupture as a temporal space, opening a field of possibilities in the interpretation of the living and its relationship to its environment. The moment of rupture is brought upon by the photographers, in an optimistic perspective, to be understood as a mutation of beings and things. Nothing is lost, everything is transformed. This project was presented in May 2018 at Mémoire de l’Avenir.

Antoine Guilhem-Ducléon’s black and white series of analog photographs were made with a 4/5 inch camera, and his series of digital coloured images were taken with a Nikon D3.

Jean-Louis Rullaud took his photographs with a Canon 5D Mark3 digital camera and processed the images with digital tools.