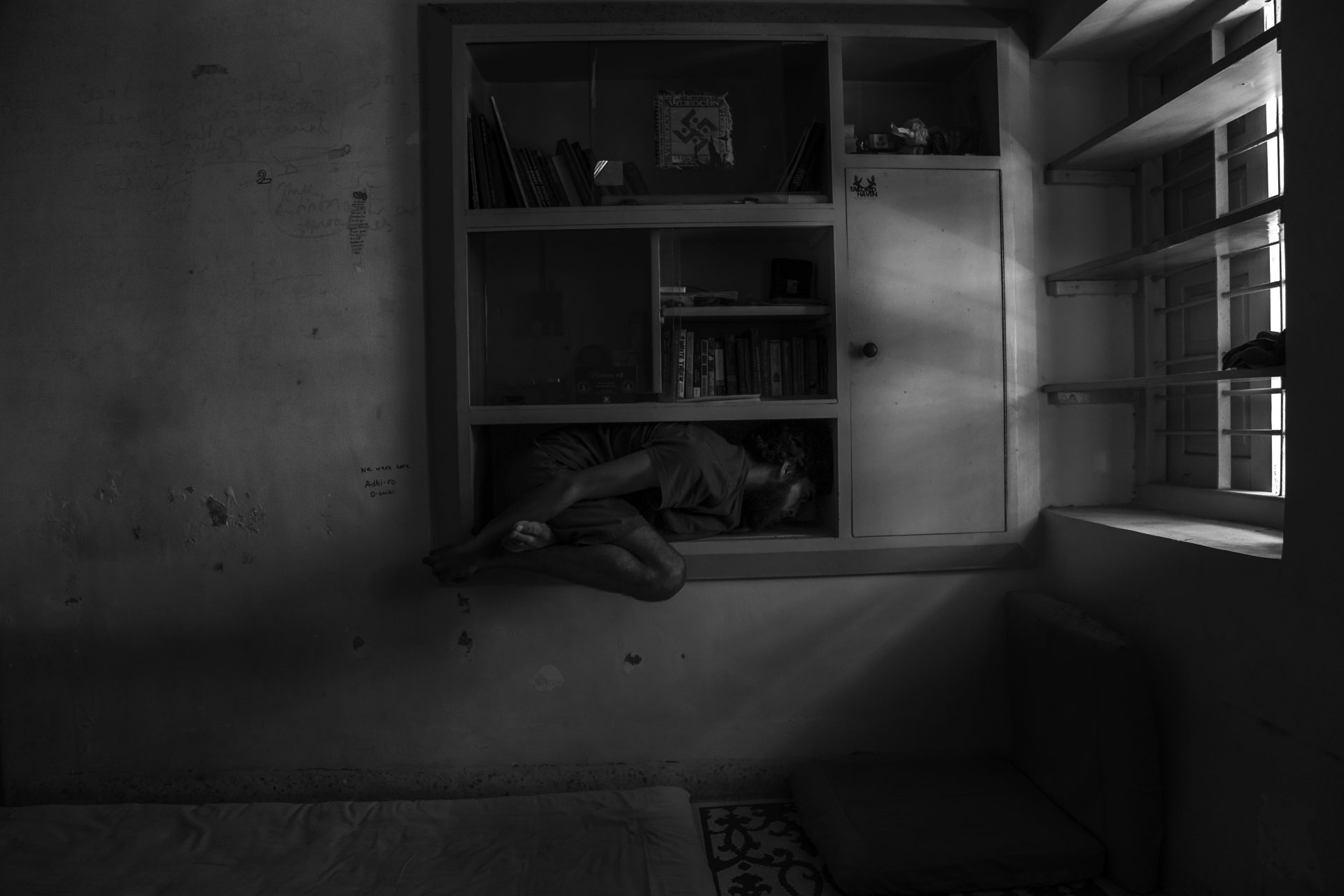

In dialogue with the series Mind and Body in Captivity by Rahul Rishi More

Hope and anxiety are expressions of one of the most human traits that we possess—the ability to anticipate—which is in turn built upon the ability to simulate the future. This ability is not unique to humans, but the degree of sophistication in its deployment is. We do not find in any other species a willingness to engage in a real estate investment that is dependent upon a complex array of social ties, familial commitments, and personal sacrifice so that they might live out their best Scrooge McDuck impersonation fifteen years down the line.

In order to understand the logic and utility of hope and anxiety, the first thing to note is that both are anticipatory in nature—they orient the agent toward possible future states of being. Anxious, the agent anticipates some negative future state, in effect saying, “Batten down the hatches, there is a high likelihood that the future will not be pleasant.” There is a use for this state—anticipation has the upside of not leaving the agent unaware of some unpleasant trial and, as such, allows the individual to engage in specific actions to mitigate it. Of course, I am not saying that anxiety is consciously presented so clearly. As a rather anxious person myself, I can attest that at least half the battle is in understanding my anxiety. The ability to understand our anxious states can be honed with time and effort, and developing it is one the many benefits of psychotherapy.1

Hope, too, is anticipatory. It orients the individual toward possible future states of being but, unlike anxiety, anticipates a positive state. In effect, it says, “No need to mobilize the troops—the future state of this being should be exactly (or near enough) to what is desired; there is a high likelihood that things will turn out well.” There is also a use for this state—it provides forward momentum for the agent to use in the achievement of goals that might otherwise seem out of reach, and it creates an energetic focus that can be immensely beneficial for the agent’s optimal functioning.

Additionally, both hope and anxiety are attempts at organization. To be human is to be practically bombarded (especially in the 21st century) with a deluge of information about the intentions and desires of other agents, the ever-evolving environment one occupies, and the increasingly global and complex societal norms that play an enormous role in determining an individual’s status within multiple hierarchies. To make sense of what William James once called “blooming, buzzing confusion,”2 we need structures to organize the state of the environment (James, 488). The way to do this is to understand what all of the incoming information means for the future prospects of the agent. This allows that information to motivate the agent. The medium of this motivation includes specific feelings which serve to guide future behaviour and cognition. Hope and anxiety are not just organizing, but egocentrically organizing, insofar as they organize the world for the agent. This is not to say that others might not occupy my perspective, but that hope and anxiety are states that involve my relationship to some possible future state of affairs.

Bringing all of this together, we can conclude that hope and anxiety are mental states that serve a specific function insofar as they help us navigate from certain (or sets of possible) psychophysical states into other (or sets of other possible) psychophysical states via their anticipatory and egocentrically organizing natures. But there is an issue with all this—everything I have said so far paints hope and anxiety as the psychological equivalents of Santa’s little helpers. But this is surely insufficient.

It may be well and good that anxious and hopeful states are supposed to work to our benefit, but the fact is that they don’t. In the 21st century, and especially in the age of COVID-19, we often find ourselves steeped in anxiety with, at most, rays of hope barely breaking through a miasma of doubt. Why this occurs needs to be explained. Why is it that ostensibly helpful cognitive mechanisms have been co-opted into causing misery? Why is hope so hard to find? This topic is as worthy as any for a deep dive, and much has been written about it (see DeVane et al., 2005 for a start). Here, I am going to touch on one factor—our environment.

To understand the importance of our environment, we need to first note a certain asymmetry between hope and anxiety. Anxiety, as opposed to hope, preys on uncertain environments, and uncertainty is, in turn, often the by-product of a lack of control. Hope, on the other hand, finds its home in environments in which an individual feels confident, knows that the environment is manageable, and if it is not, the individual can make it that way through exercising control. The asymmetry becomes clear when we realize that, due to the many pressures we encounter, a feeling of lack of control is much more likely to occur than a feeling of control. This at least partly explains the prevalence of anxiety.

In our globalized world, we increasingly exist within multiple social networks, each with unique hierarchies that require different behaviours, a deeper understanding of the dangers that threaten our survival, and a growing awareness of unequal power distributions that are highly resistant to change (in fact, seem to be getting worse). In a word, we live in a world filled with uncertainty, which acts as a hotbed for anxiety. What hope can hope have in such circumstances? And what are we to be hopeful for?

Thanks to technological innovation, the world is changing at a rapid rate, and presents challenges that we do not know how to manage. For example, how ought I to represent myself on [insert your favourite social media platform here] in order to be accepted by my peers? We find ourselves having to be available at all times to our friends on these platforms, and to represent ourselves at our absolute best. How do I communicate in the way I intend, with subtlety and nuance, via text message and email? There are many non-verbal cues that are communicated in face-to-face interactions that cannot be imparted online, where messages can easily get distorted. How do I create friendships with other individuals if they are constantly glued to their phones (Turkle, 2012)? The kinds of spontaneous interactions that lead to friendships and other relationships have seemingly evaporated. Given time, these unique challenges can likely be overcome, but the adjustment period needed to figure out how is non-existent. The rapid rate of technological innovation often does not grant this luxury and can lead to a destabilizing lack of control (Anderson & Rainie, 2019).

Recognizing this, it should not be surprising that anxiety has such a grip on so many lives—heartfelt optimism doesn’t stand a chance in such environments. In fact, an argument could be made for the desirability of irrational hope. Given our circumstances, it might be best that, in order to live the lives we desire, we not acknowledge our uncertainty that we encounter. Doing so might minimize the already small chance of hope to blossom. One might argue that what we should do is hang our rational hats at the door and act as if things are more stable than they actually are, so we can at least attempt to maximize our chances for desirable lives. The fact that our best hope might be to ignore the reality of our situations should tell us something—that our environment is in deep need of repair.

The need to reform our environment has public health dimensions. Constant feelings of anxiety have a tendency to morph into a chronic condition—generalized anxiety disorder (NHS 2018). For those that struggle with this all-too-common affliction, their lives are permanent battlegrounds, with anxiety the norm rather than the exception. Chronic anxiety is not just harmful to the sufferers’ social lives and mental well-being, but to their health, and may even be damaging to their brains. The reason for this is that stress responses have specific neurochemical profiles (Sapolsky, 2018, 124-127, 143; Martin et al., 2009, 551), and these neurochemicals, while relatively benign in the short term, are toxic in the long term.

So how do we move forward? We begin by acknowledging that anxiety and a lack of hope are partly systemic issues, and that we can attempt to mitigate them by simultaneously working on multiple fronts. Individually, we need to gain an increased awareness of how anxiety functions, and what anxious states might be telling us, so that, through a better understanding, we can more successfully manage them.

First, we need to encourage individuals to seek help when they need it. Individuals need to be able to recognize abnormal states of mind as abnormal and move to take action to manage them. Building on this, we need to encourage individuals to focus more on questions about how to live and what it would mean to attain a sense of well-being. We can do this by encouraging individuals to ask themselves questions that are currently considered antiquated or self-indulgent. Examples would be: What does it mean to live a good life? What aspects of life are worth pursuing? How can we find meaning in this life?

Second, on a societal level, we need to acknowledge anxiety as a public health issue and approach it with at least the same level of tenacity that we use in addressing nutritional and dietary concerns. We can do this by eliminating the stigma of mental health counselling and making counselling accessible to everyone. We also need an increased, systemic emphasis on teaching our youth (and our adults) how to manage stress (see Cromwell, 2016 as an example of how this might work). There are techniques such as mindfulness meditation that are available to combat anxiety, and we need to assimilate them into our society in the same way we’ve inculcated physical exercise.

Third, we need to give people reasons to feel hopeful by providing them with opportunities and jobs that actually provide meaning. There needs to be more equitable employer/employee power distribution, so that the life of the working person is not entirely out of their control. Additionally, we need to change social power dynamics so that power is not rooted in economic success to such a great degree. A shift in values in which more respect is accorded to those who dare to step outside the norm and risk a more creative life would go a long way toward making more people feel seen.

Finally, what needs to be erased is the insidious conceptual bifurcation in which mental health and physical health are thought of as belonging to different domains. From a neuroscientific perspective, the only real difference between the two is that the techniques to fix the former are more complex and variable for a given individual than the latter. This is a problem of sophistication, not of kind (Ackerman, 1993). Anxiety is largely intertwined with our environment, and to my mind, it is only once we grapple with and fully appreciate that fact that we can make any meaningful progress in this area.

- One of the hallmarks of cognitive behavioural therapy (a type of psychotherapy) is to challenge the linguistic representation of this anxious state and to dialectically resolve the unconscious beliefs underpinning the feeling (Mayo Clinic, 2019).

- Though it should be noted that he expressed this in relation to the conscious states of children.

Bibliography

Ackerman, Sandra. Discovering The Brain. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1993.

Anderson, Janna and Lee Rainie. “Concerns About The Future Of People’s Well-Being And Digital Life.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Pew Research Center, December 31, 2019.

“Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.” Mayo Clinic: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, March 16, 2019.

Cornwell, Paige. « Schools Create Moments Of Calm For Stressed-out Students ». The Seattle Times. The Seattle Times Company, December 9, 2016.

DeVane, C. Lindsay, Evelyn Chiao, Meg Franklin, & Eric J. Kruep, 2005. “Anxiety disorders in the 21st century: status, challenges, opportunities, and comorbidity with depression.” In The American Journal Of Managed Care, 11(12 Suppl), S344–S353. “Generalised Anxiety Disorder In Adults.” Accessed September 15, 2020.

James, William. Principles Of Psychology. New York: Cosimo Inc., 2007.

Martin, Elizabeth I., Kerry J. Ressler, Elisabeth Binder, and Charles B. Nemeroff. “The Neurobiology Of Anxiety Disorders: Brain Imaging, Genetics, And Psychoneuroendocrinology.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 32, No. 3 (2009): p. 549–75.

Sapolsky, Robert M. Behave: The Biology Of Humans At Our Best And Worst. New York: Penguin Books, 2018.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology And Less From Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Farhan Lakhany is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Iowa. He received his undergraduate degree in Philosophy from the University of North Carolina and his masters degree in Philosophy from King’s College in London. His philosophical interests are related to the mind, psychology, language, mental health, methodology and the theory of Ludwig Wittgenstein. His current research focus is in evolutionary explanations of consciousness and deep philosophical disagreement.

Rahul Rishi More is a visual artist from Dumka in Jharkhand, India. He received his Bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Fine Arts Baroda at the Maharaja Sayajirao University with a specialization in moving images. In his work, he seeks to incorporate experimental approaches to image making and explore the politics between nature’s simplicity and the complex behaviours of humans.

Farhan Lakhany is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Iowa. He received his undergraduate degree in Philosophy from the University of North Carolina and his masters degree in Philosophy from King’s College in London. His philosophical interests are related to the mind, psychology, language, mental health, methodology and the theory of Ludwig Wittgenstein. His current research focus is in evolutionary explanations of consciousness and deep philosophical disagreement.

Rahul Rishi More is a visual artist from Dumka in Jharkhand, India. He received his Bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Fine Arts Baroda at the Maharaja Sayajirao University with a specialization in moving images. In his work, he seeks to incorporate experimental approaches to image making and explore the politics between nature’s simplicity and the complex behaviours of humans.