The laqueur artist, her masters and her daughter

Mireille Herbst did not choose to be a lacquer artist. It is the lacquer that chose her. After training as a graphic artist, she replied to a short ad and discovered, with great amazement, a craft handed down by the great lacquer masters. She continues to explore this craft today and in her own turn, hands it down to the next generations through her daughter, who has been an associate of her workshop ALM DECO, created in 1994.

Lacquer art continues to preserve its mystery. For a long time, it was a privilege of the Eastern hemisphere – first in China and then Japan. Lacquer had its moment of glory in France during the Art Deco period. During this time, Jean Dunand and Eileen Gray turned lacquer into an art of its own right, still inspiring lacquers today.

Mireille Herbst, who has been managing ALM DECO since its founding in 1994, speaks about her learning of lacquer from her different master craftsmen, the impact of beauty on her life, the importance of transmitting the secrets of the craft and shares her hopes and fears for the future of this grreat art.

Mireille, what made you want to be a lacquer artist? Did you choose this profession before starting your studies? Or did the lacquerwork come along the way?

I was 18 years old, in 1974, when I finished my training in graphic art. With the technician’s certificate (brevet de technicien) in my pocket, I replied to a small ad: “lacquer seeks young girl who knows how to draw”. During my trial period, I made Chinese motifs and watched in amazement as the lacquer artist transformed what he touched into gold. So I spent a year and a half making Chinese style copies.

Then, I learnt to reproduce ancient models and to restore Chinese and Japanese lacquerware with Henri Louis Dupard.

In another workshop I had to make all kind of Chinese style lacquer, working as fast as the Chinese craftsmen in the “Faubourg Saint-Antoine » (popular district in center east Paris where the cabinet making craftsmen workshops and furniture shops are located).

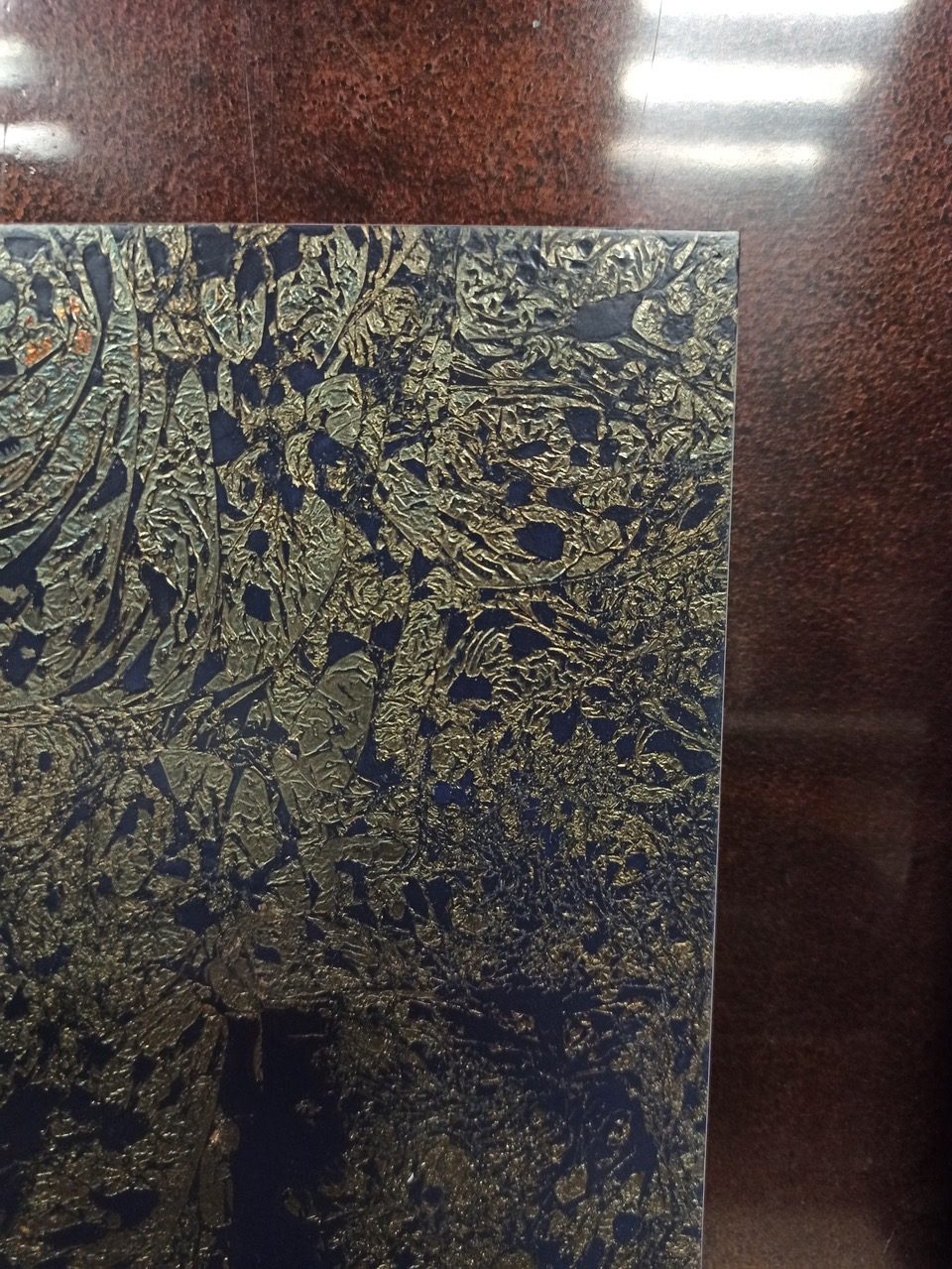

When the popularity of this style passed, we started producing Art Deco styles inspired by Jean Dunand and Eileen Gray, which opened my mind.

The atelier Saïn & Tambuté and the fire-resistant lacquer that they had developed (a polyurethane applied as lacquer) often came up in conversations. This made me want to discover the secret and to work in this famous workshop. Thanks to a client who knew they were looking for a craftsman, I started working with them.

After your first experiences in these different workshops, how did the transmission happen with Saïn & Tambuté? Tell us about the different steps of learning.

When I joined the famous workshop of Saïn & Tambuté in 1989, Tambuté had passed away and given his workshop to Bernard Roger. Saïn, who had retired from the business, still came in sometimes and continued to create boards and folding screens. Bernard Roger had hinted that he wanted someone to take over the workshop.

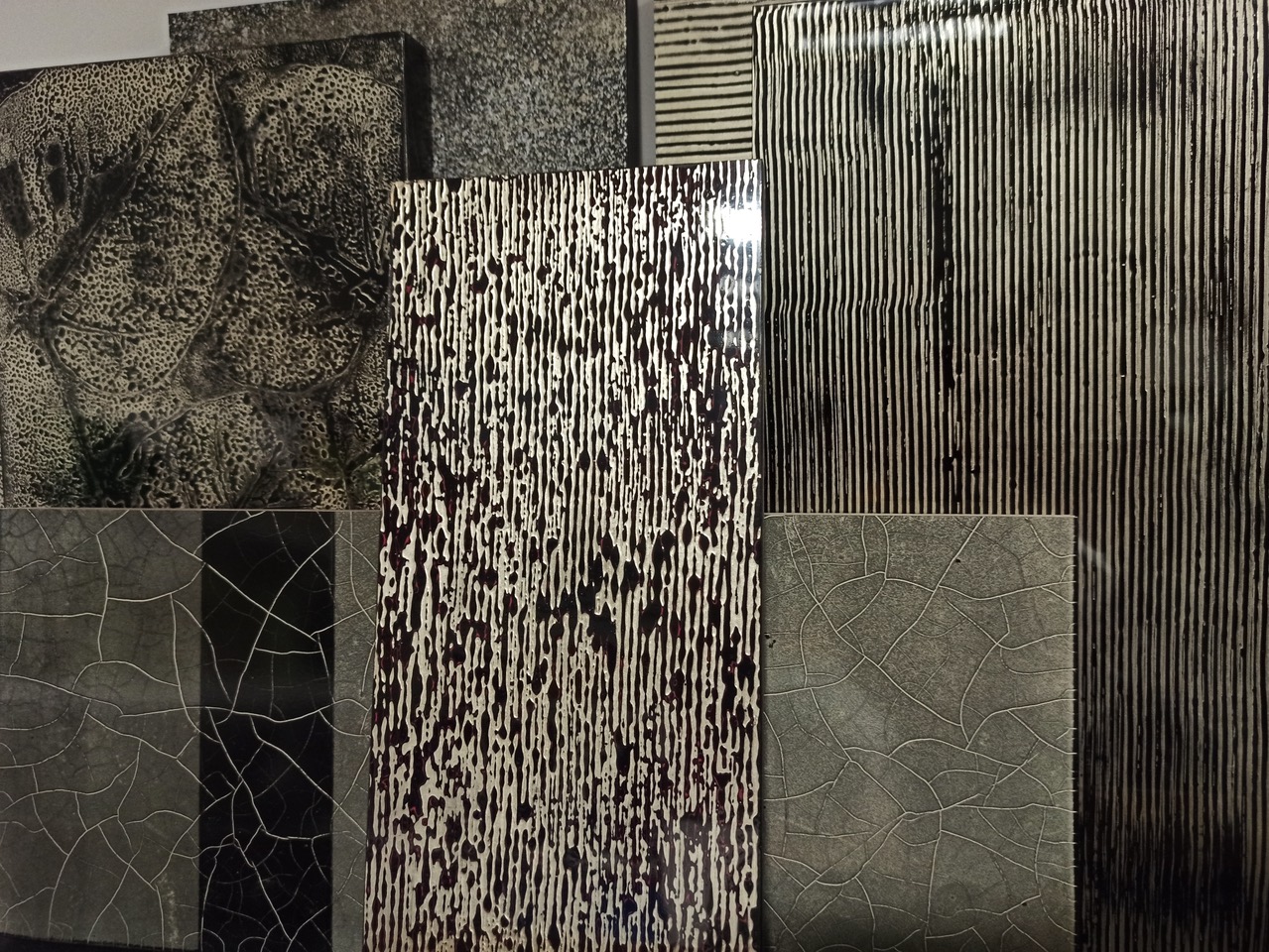

Bernard Roger taught me to do good work, perfection, endurance, to reflect on what we do and how we do it, and to find methods to not waste time. He gave me self-confidence and, for the first time, I was in contact with the customers, I participated in the creation of materials and motifs (in the Art Deco style). For example, I had developed a chair with a lacquer on which applied cotton fibres, so that the remaining particles had a textural effect.

Bernard Roger decided to retire at the end of 1993. Even though I didn’t know the technical and management side, I decided to go ahead and take over when my daughter Nora was 5 years old.

As the lease for faubourg Saint-Antoine, where the workshop was located, was not being renewed, I moved to le Prè-Saint-Gervais (in the North Eastern part of Paris) to create a new business, keeping my old colleagues, a lot of material and especially the clients that came along with me!

From the old workshop, I kept boxes of drawings and an old book of lacquer recipes and samples. A lot of these references don’t exist anymore…

In their time, Saïn & Tambuté had worked for grand decorators and designers such as André Arbus, Baptisin Spade and Jules Leleu. Today, I still restore furniture made by predecessors that have become antique objects.

What were your hopes and perspectives when you started this profession? How did you imagine the future?

I was incapable of projecting myself. My father told me «You have to work well in school so that your future boss will be happy with you. » I was docile and obedient. Then, when I took over the business, I followed in the steps of Bernard Roger and it took me 10 years to realize that I should have done things differently. Since I had a good customer base and the workshop worked well, it was enough for me. I had not shown what I was capable of.

Have you had moments of doubt on your professional path?

Doubts have always followed me! I thought that other craftsmen did better than I did, until the day I joined associations. I understood the problems that were intrinsic to the profession and I felt a lot less lonely. Being part of a network, talking about different subjects and exchanging with others has been greatly beneficial for me.

Did you imagine your profession to become what it is today?

Competition is tougher. When I started, there were four workshops of lacquer artists on the same level and lacquer had a very specific use. Today, decorators don’t hesitate to replace it with straw marquetry, glass, metal or decorative painting. These are beautiful materials, but I can’t help thinking that they are stepping on my toes.

When I started working, decorators were loyal. When they had a project, they went to see their cabinetmaker, their varnisher, or their lacquer artist. Today, they tend to ask for several quotes and opt for the cheapest and flashiest projects. In order to make ourselves known, we have to do a lot of communication, which impacts the prices that we charge our customers.

Is the pandemic a source of worry? Or a new moment to search for, create and invent new materials?

A bit of both. During the first lockdown in France, I had to ask the workers to stay at home, which was a real worry. I went in to work every day telling myself I had to create a board, but I did not have the heart to do it. The idea of not being able to complete my orders worried me. This period is very anxious because we don’t know what tomorrow will be like.

Nora, what made you decide to learn the craft and join your mother in the workshop? How did the handing down of knowledge happen between the two of you?

Since I was very young, I spent time in the workshop and have also been always drawing. During our vacations, I remember going to Bernard Roger. He made models of boats, carousels and his designs. Following this, my mother bought me a scroll saw with which I could make small objects.

I first came into the workshop to manage the administrative and communication parts of the business. Then I decided to learn the profession so that the workshop would not disappear when my mother will retire.

There were no training programmes to learn lacquer art, so I did the adult professional training course at the Ecole Boulle in Paris. I really like to work with my hands. After this training, I continued to learn with my mother and the guys at the workshop. The best way of learning was by doing.

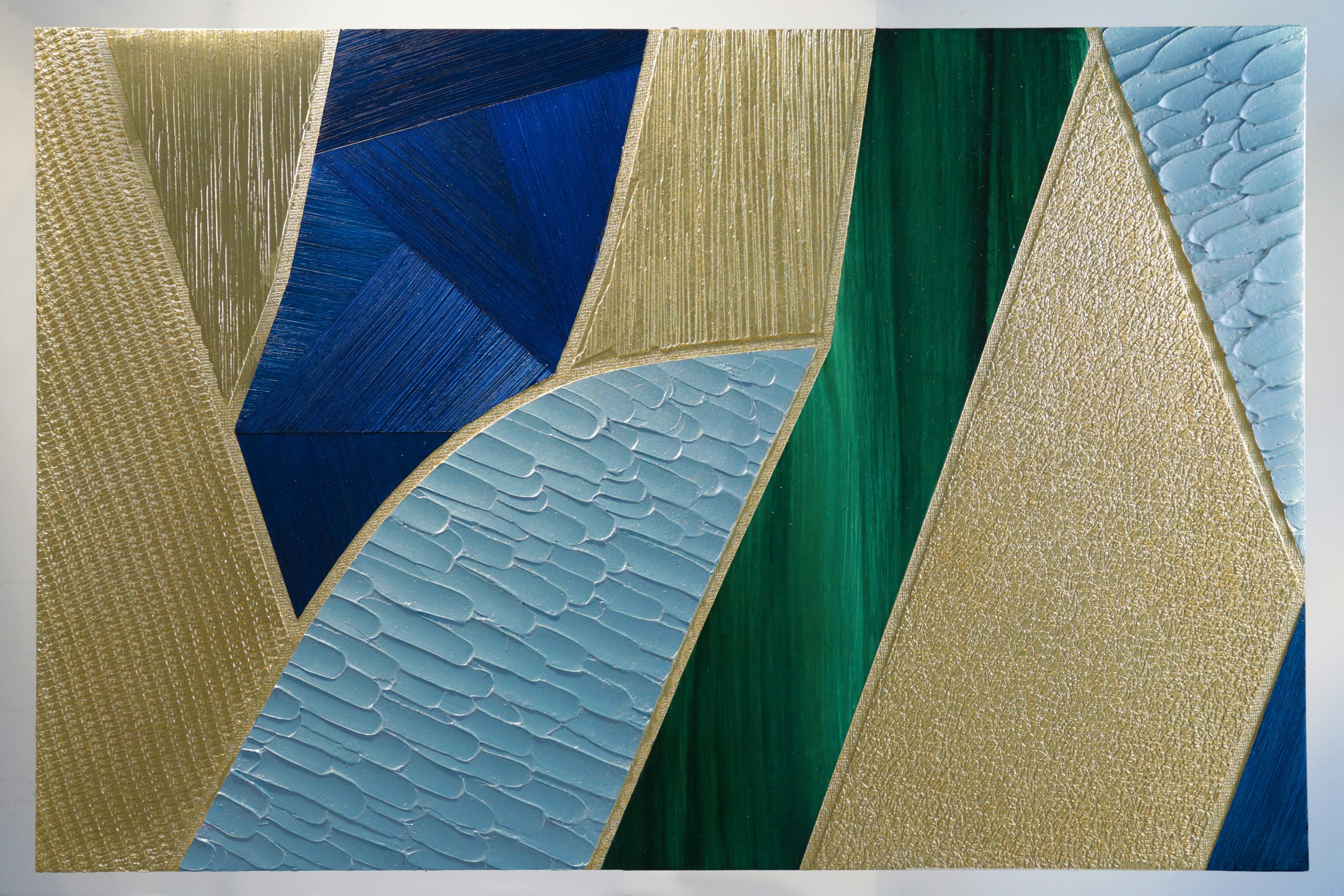

It’s a craft in which you learn new things every day, where evolved modern techniques combine with ancient techniques and with the history of our predecessors.

What do you expect from the lacquer craft?

I would like for the image of lacquer to be less outdated. I would also like to raise awareness of its potential and the infinity of possibilities, that it loses its reputation of being fragile, that it gives new confidence to the customer base and that it reaches a new generation that gets to know its eternal modernity. I’m waiting for people to learn again that quality is earned through effort, patience and that time and a job well done come at a price.

Nora, how do you see the future of your craft? Of the workshop? Of this art form?

I would like that the lacquer craft maintains its authenticity, that the art of lacquer doesn’t become a business that responds to a race to the bottom. I expect from the craft to stay as it is while adapting itself to modern times.

I would also like for the workshop to remain an authentic space, where the human is at the centre, that it opens its doors to the curious who want to learn the love of craftsmanship, that it will teach the most motivated, that it will welcome beautiful projects so that this art can continue to live, with respect for the object that it enhances and that it allies itself with the current trend of fight against consumerism.

The art of lacquering maintains its soul because it is an answer to a problem of the already obsolete new. With lacquer, you can offer yourself an object, a piece of furniture that will last a lifetime. Lacquer can be restored and reused. You don’t throw it out because it’s damaged or obsolete. If you get tired of lacquerware, its intrinsic value allows you to resell it. By acquiring it, you enrich its heritage.

How did what Mireille learnt from her masters pass onto you and transform?

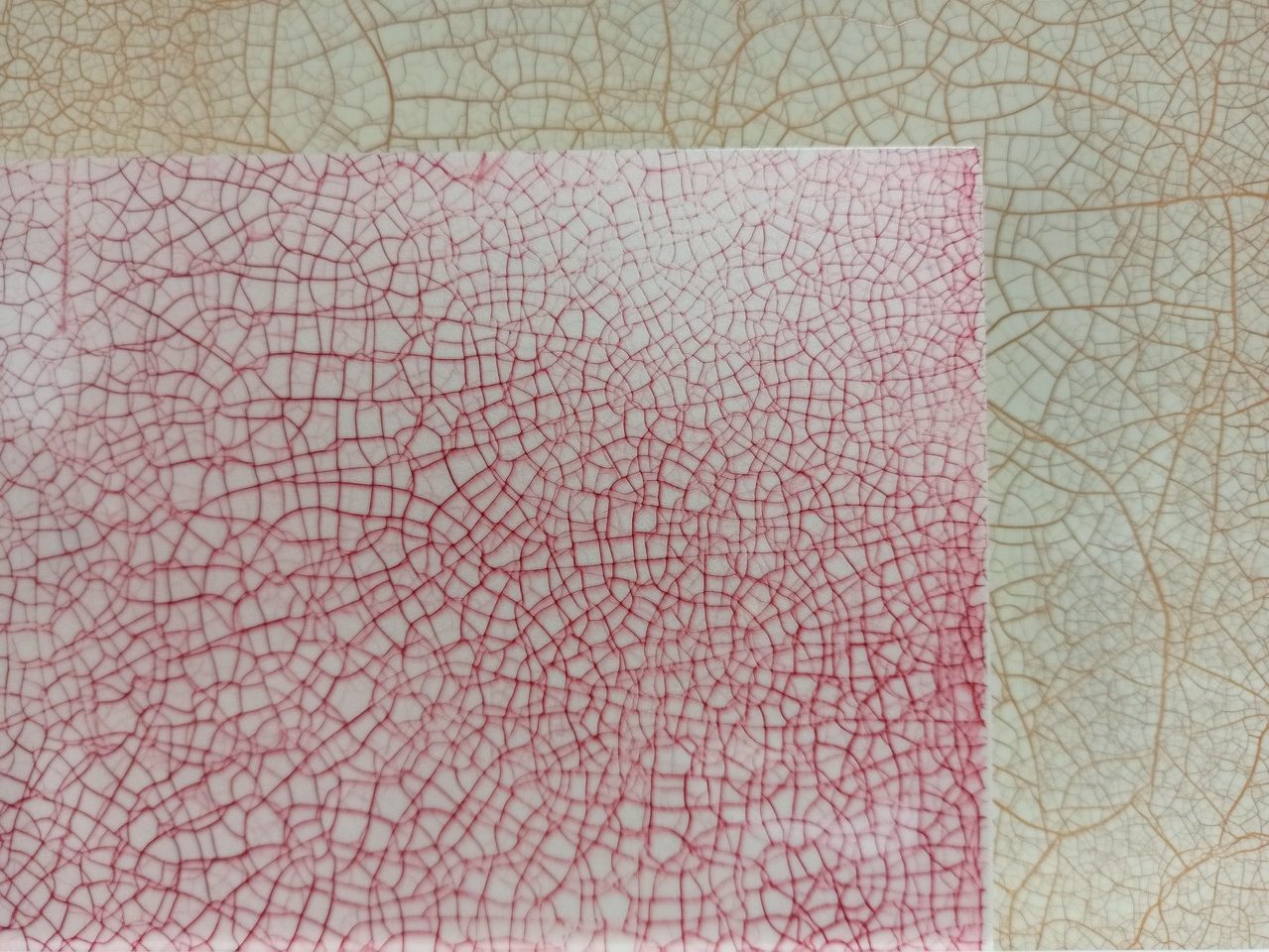

Lacquer is surprising. It always gives new results. We are endlessly searching for new finishings and decorations. Its possibilities are such that we always try to do something different from what we see most of the time!

Can lacquer be applied to new bases?

Our latest research has shown that we could make 3D prints and use lacquer on plastic, PVC and glass. The reputation of it being fragile is outdated. We have tested it on glass with several of our colours.