The glassmaker Bernard Pictet officiates in a small workshop of under ten people, located in the heart of the Oberkampf district in Paris. His workshop specializes in glass facings and partitions, commissioned by architects and interior designers from all over the world, to decorate luxury stores, hotels, yachts, and private homes as well as museums and universities. Each piece of glass goes through the hands of craftsmen who apply skill and knowledge inherited from the decorative arts tradition.

An artistic process reserved for the elite

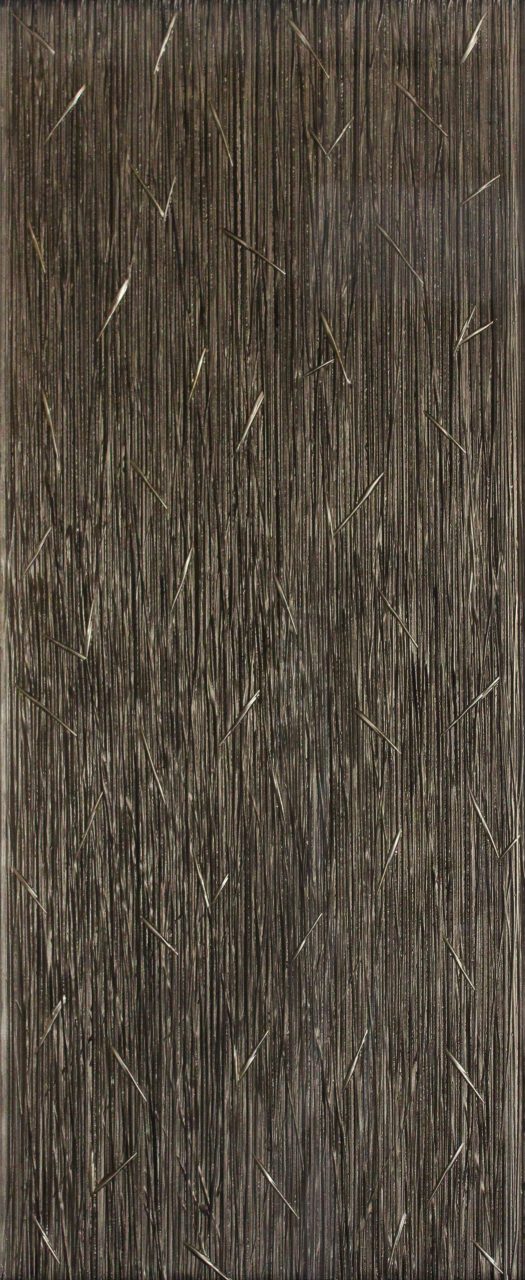

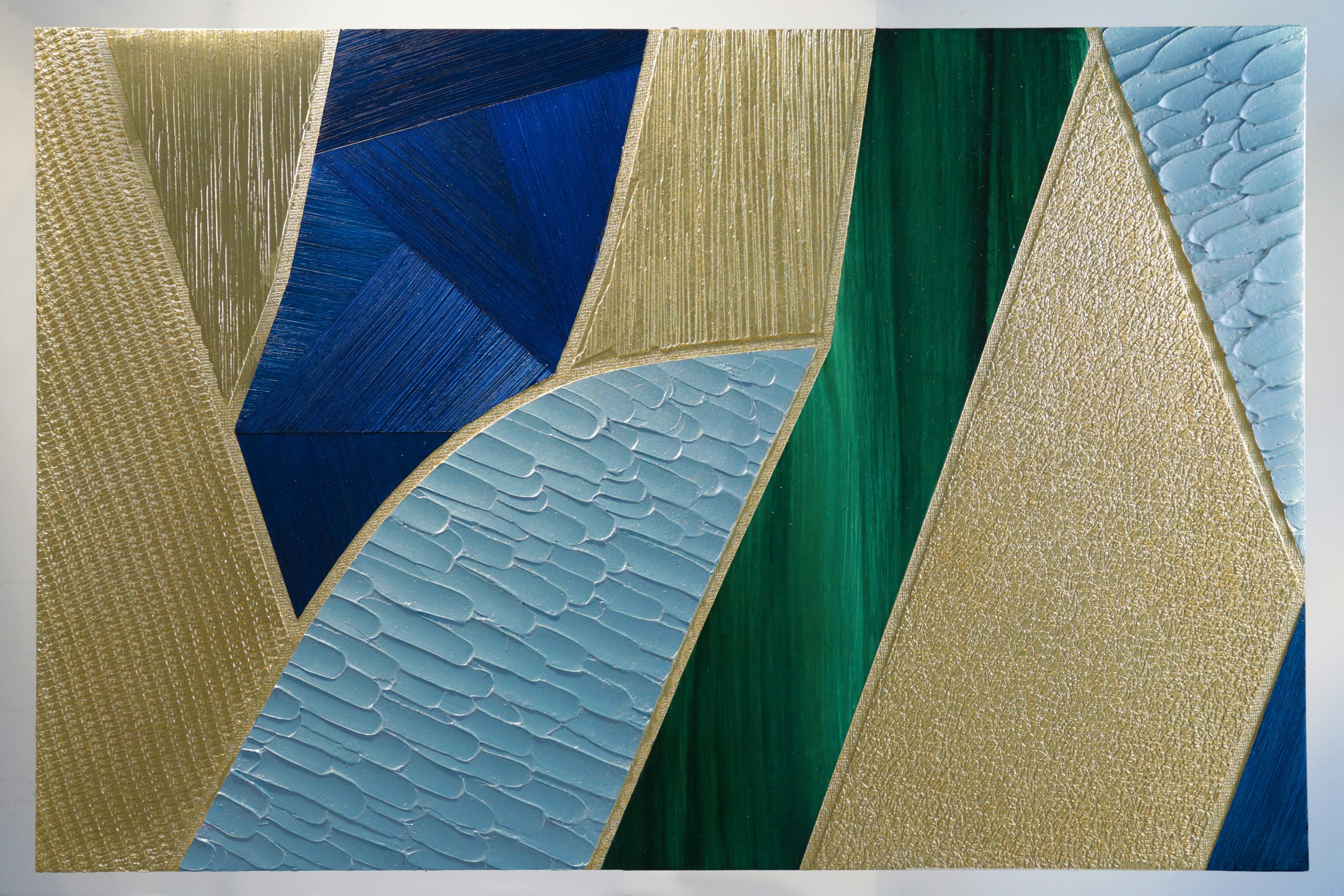

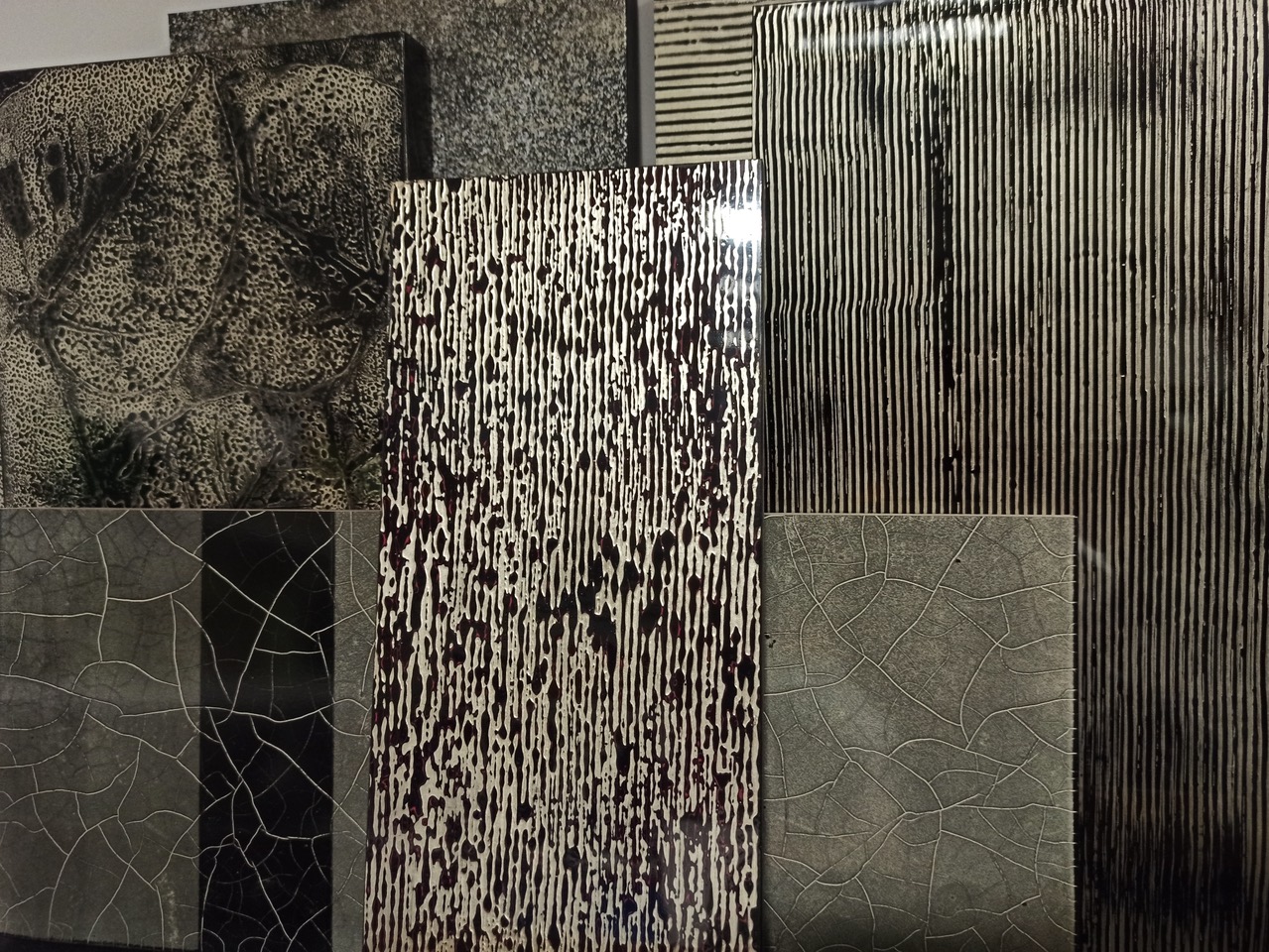

Bernard Pictet has incorporated new techniques such as diamond-point and saw engraving. He also uses screen printing to obtain results ranging from coloured to unpolished and mirrored. Each of his handmade creations is a display of imperfection and uniqueness highly sought after by the most demanding interior decorators. His glassworks do more than play with light—whether transparent, translucent, opaque, or reflecting, they are perceived as exceptional in both materials and texture.

Like most craftsmanship, Pictet’s trade was once available to all, before the age of mass production. Today, however, considering the time spent on each piece, his work can only be afforded by the elite. His daily practice with glass resembles an artistic process; his inspirations and his extensive technical knowledge of glasswork are endless. Nothing could seem further away from this Parisian craftsman, transforming glass through traditional techniques, and who was granted the EPV label, than the world of big data.

Who could have guessed that the multiplication of data on the internet and on social media could have impacted the creative process of this traditional craftsman? And yet, data globalisation has indeed fed, revamped, and expanded the art of Bernard Pictet, who in turn brings his own inspirations to the world wide web. He answered a few of our questions below.

How would you define your work, from the perspective of the creative and technical process?

You cannot define creation! Life is inspiration in itself, whether it’s a work of art seen in a gallery, an atmospheric change in the sky, or a shop sign seen on the street, anything can be turned into creative material from the moment it moves me. Whenever I start to look for inspiration, I usually end up finding it accidentally! I make it a point of honour to keep an open mind. I can find inspiration in anything I see, but I only keep what creates feeling. One of my leitmotifs is diversity.

The only time I don’t look for inspiration within my own sensitivity is when I am given a particular theme for commissioned work, such as water, fire, geometry, or a reference to a specific period in the decorative arts.

I have been practicing the craft of glassmaking for forty years. From a technical perspective, this experience with the material helps me to determine the technique or techniques that will best express the result I’m looking for. Certain techniques can adapt to the project I’m working on, whereas others may not apply.

Where did you look for inspiration when you started working with glass?

In books on decorative arts. At that time I was also lucky enough to have the King of Morocco as one of my most important clients. That led me to start looking into geometric patterns in traditional Islamic arts, which I mainly found in an extraordinary book on the subject by André Paccard.

Since gaining access to a global data base through Pinterest and social media, how have you come to use it?

I browse on Pinterest, searching either by theme or through the boards of members I’ve subscribed to. Pinterest’s algorithms, having memorised my previous searches, offers me a selection of links in relation to my points of interest and prior searches. I either find sources of inspiration directly from this pool of images or I use the algorithm’s results to look for new inspiration.

Would you say this way of conducting research is more time-consuming than the “old fashioned” way?

It’s less a matter of time than it is of data volume. When I relied solely on books for my research, I could find a dozen images in a book, whereas today I can find thousands. Finding as many images the traditional way, in books, would of course be far more time-consuming. The online searches do not keep me from consulting art books or exhibition catalogues. Currently, approximately 80 to 90 percent of my work is inspired by Pinterest content.

How do you go from enormous volumes of information to a unique custom-made piece?

After conducting my research, I make an initial selection with the studio’s computer-graphics designer. I then examine that selection on vector graphics software in order to figure out which elements could be exploitable. Once that step is completed, we create our own interpretation on that same software. The second-to-last step is making a sample with glass. The choice of the most appropriate engraving style or technique comes at the end.

Has this process brought about any changes in terms of technique?

Perhaps on the level of graphic design, but certainly not in the fabrication process, with the exception maybe of screen printing. Pinterest is a source of ideas in terms of patterns and shapes, but it does not provide any insight in terms of effects such as light or layering. A visual form can, however, inspire a new technique. For instance, it was a very fine visual form that gave me the idea to try the diamond-tip engraving technique (see the image of Nénuphar).

Would you say it’s a positive advance that allows you to draw from the world of art and interior design, thus remaining alert and in advance on what’s trending?

Absolutely. But I consider my work to be beside fashion. I observe it with great interest and I can even make use of it, but it’s very important to me that I don’t get too involved in trends. In the words of the philosopher Jean Guitton, “Keeping up with the times will only destine you to the fate of dead leaves.”

Your work tends to circle back to big data, enriching it in turn through images shared on your website and social media platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest. How do you maintain uniqueness when images of your work are spread and reproduced?

Taking a good photograph of glass is an extremely difficult task. Reproducing three-dimensional glasswork from a photo is practically impossible. Certain samples are extremely complex creations, so most of the time people, even if they like what they see, have a very hard time understanding the piece’s materiality. The materiality of some glass creations is even hard to discern in real life!

Can we touch upon the notions of one-of-a-kind and copyright?

In no way do I copy patterns—I reinterpret them or use them as inspiration. Copying would be impossible given the fact that my tools and materials are never the same as the ones used in the works I draw inspiration from.

Regarding the images shared on the workshop’s website and social media accounts, every piece is trademarked. Posting images of our creations on social media is a double-bladed knife. We have to show our work in order to make ourselves known, but at the same time we are exposing ourselves to plagiarism.